This is a post that would normally be behind my paywall as part of my creative writing series, wherein I take risks, post photo essays, review Woke books to mock them viciously, post writing experiments, and tell personal stories. In the spirit of Thanksgiving this one is free for all readers. Paid subscribers have access to my series on How to Not Suck at Math, as well as comments when they’re turned on (weekends for now; weekday comments will return when I’m more settled into my new job). If you enjoy it, there’s a Black Friday sale on paid subscriptions.

Comments are open for paid subscribers until Sunday night, December 8.

Earlier today, my unconscious mind pulled one of its more perverse tricks on me. It wasn’t the first time.

It’s a story my therapist knows so well that we have a shorthand for it.

This happens because of a strange dynamic in my thinking—a dynamic that’s always running in the background.

It’s a mechanism that takes hold when you’re screwed up enough that getting better becomes your deepest desire.

You might understand the power, importance, and beauty of living in the moment. You might fully grasp how a lack of mindfulness sabotages happiness. You might even be committed to living out these ideals daily—and still fail miserably. Why? For a reason so ironic it’s almost absurd.

When getting better is your ultimate goal, the part of you that wants it so desperately becomes hypervigilant. It’s constantly monitoring your thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and perceptions, searching for evidence of progress—to celebrate, to build hope, or simply to feel good about yourself. (When you’re self-monitoring this much, feeling good about yourself is rare enough to seem novel.)

This kind of fragmentation—where different parts of you run conflicting programs simultaneously—is common among people who are deeply stuck. And yes, it’s as confusing as it sounds.

That self-monitoring part, what my therapist calls the “chief product inspector” (an annoyingly apt metaphor), ends up being its own obstacle. By constantly watching and evaluating, it prevents you from integrating those fragmented parts and being fully present.

Ironically, the desire to improve becomes the very thing that blocks improvement.

That’s the perversity behind the stunt my unconscious pulled earlier. I’ll share that story before this post is over, but for now, two things stand out:

First, I’m grateful I spotted it—without needing my therapist to point it out.

Second, I’m very, very grateful I can laugh at myself.

Yes, this is a post about gratitude, on the night before Thanksgiving.

Not an original idea—if you subscribe to multiple Substacks, you’re likely drowning in gratitude posts this week.

But I relish a challenge, so here’s my take: gratitude for the difficult-to-admit, the hard-to-describe, and the darkly funny. Gratitude that’s perverse in its own way.

I hope this will be interesting enough to justify your time—even if it’s the tenth or twelfth gratitude post in your inbox this week.

Gratitude for Helping: 1

A friend of mine is married to a good guy—a genuinely kind, caring person. He’s not a Woke caricature. He rolls his eyes at neopronouns and knows it’s absurd that boys are allowed to play on girls’ sports teams.

But he believes the mainstream media. Entirely.

After Trump won the recent election, he had my friend—who has a serious anxiety disorder, like me, and really didn’t need this kind of stress—so upset that she was panic-texting me in the middle of the night.

What was he doing?

Over dinner, he was doing math. Specifically, calculating how many Muslims they could hide in their attic when Trump started building concentration camps.

I wish I were kidding.

I’m grateful that she was able to really hear me on two important points.

First, I told her that the idea of Trump as a potential Hitler was obvious bullshit—and that she could be absolutely certain of this for one very simple reason: the Vice President had called him and made arrangements to peacefully hand him the nuclear codes.

“Think about that,” I said. “Nobody peacefully hands Hitler the nuclear codes.”

She thought about it, repeated it to herself, and felt some relief. It even made her a little angry—as it should have! She started to recognize how deeply the media and certain politicians had manipulated her emotions, pushing fear they clearly didn’t believe themselves.

Second, I asked her to reflect on whether she felt pressured to be upset.

“Is it possible,” I asked, “that part of your fear comes from a sense that you have to feel this way? That being terrified is a way of signaling that you don’t support Trump? That if you weren’t visibly distressed, someone might mistake you for a Republican?”

She paused. Then she admitted I was right. That was part of it. Over the next week, she texted me several times as she noticed how much this pressure to perform distress was everywhere—on social media, in her conversations, even in her own thoughts.

She’s now on a social media fast, and she’s feeling much better.

Her experience reminds me powerfully of how desperately our society needs emotional containment, something I wrote about earlier this week.

Gratitude For Being Helped: 1

Something psychological messed with my sleep almost every night from mid-March until the weekend of November 16—about ten days ago. I’ve dealt with a serious sleep disorder my entire life, but this was worse. Much worse.

For a while, it got so bad I couldn’t reliably tell when I was awake and when I was asleep.

Why did my sleep deteriorate so drastically? I’m not ready to write about the details anytime soon, but I was alone with something that tortured me—not just with its presence, but with its implications.

It was bad. And my standards for “bad” in this realm are very goddamn high.

My mind has always saved its heaviest artillery for the dark hours when I’m alone, trying to fall unconscious.

Some of my recurring nightmares are disturbingly perverse, like the one where someone is breaking into my apartment, climbing the stairs to harm me. In the dream, I think I wake up and take action to defend myself—only to realize, later, that I’ve just woken up from a nightmare about waking up from a nightmare.

It usually takes half an hour to convince myself I’m actually awake after that one.

For eight months, my nighttime battles were exponentially worse. I began to wonder if they would ever get better.

Then, ten days ago, something changed. The very high capacity for human kindness in a very good person asserted itself. This person made helping me a priority, and suddenly, I was no longer alone with the thing that had been torturing me. That turned out to be 80% of what I needed for relief. The other 20% came from the conversation itself, the contents of which are still echoing in my mind in helpful ways.

Since then, I’ve slept so much better that the difference has been nothing short of life-changing.

And I am so grateful.

Gratitude for Struggle: 1

The perverse trick my mind played on me earlier today—the one I mentioned at the beginning—was related to my new job.

My boss is an interesting guy. He’s profoundly smart and, I’d bet my left kidney, on the autism spectrum. Mathematics has more male autists than any other field, and after endless conversations with professors, TAs, and others (including briefly dating two PhD students), I trust my radar for spectrum-y dudes.

In the couple of months I’ve worked for him, I’ve learned an astonishing amount. At my old job, nobody else on my team coded, and all anyone ever saw was my finished product. As a result, I had no idea how ugly my coding really was—effective enough, solid on logic, but highly inefficient and absurdly overcomplicated. Without feedback, I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

Under his guidance, I’ve learned about Test Driven Development, idempotence, keeping functions small and easy to reason about, and much more. I’ve improved massively—but I only know that because I’ve studied on my own, not because he’s said a word. (Spectrum-y dudes don’t do positive feedback. It’s not meanness or coldness; they’re just wired differently. They don’t realize—or care—that you might need it.)

The combination of my 24/7 autodidact improvement crusade and the normal stresses of being an anxious freak in a new job has made these past months deeply uncomfortable.

I’m not complaining. It’s not the bad kind of stress. I’ve grown, learned a lot, and developed my capacity to tolerate intellectual discomfort—and to exist without praise or positive feedback. All of that is good. But it’s also hard.

My therapist has been quick to point out the therapeutic value in this, and I’ve tried to lean into it. Earlier today, I turned in a report. I have no idea if it was “good” because I don’t know enough to calibrate such things yet.

But I do know this: it’s much, much better work than I was capable of two months ago. And that’s both the best I can do and an achievement in itself.

For the first time, I realized I wasn’t anxious about my boss’s response. I knew I had done my best—and that my best had improved dramatically since day one.

That was enough. It was more than enough. And I was proud of myself.

Even if the report wasn’t what he wanted and I have to redo it next week, I’d still be proud. In that moment, I felt a deep sense of self-reliance, noticeable growth beyond my old insecurities, and the rare and precious feeling of being genuinely proud of myself.

And what did I do with that moment of glory?

I immediately jumped into the private Discord channel I share with my dear friend

and told him about it—thereby negating the personally therapeutic aspect of the achievement entirely.“Hey, friend! Want to congratulate me for my marked progress in growing beyond needing external validation and congratulations?”

I laughed so hard—but not as hard as my therapist is likely to laugh.

Ah, well.

At least I spotted it. Usually, he’s the one who points these things out.

Usually, he asks, “Has the chief product inspector given you any other awards you’d like to revel in, instead of living your life?”

He’s a magnificent bastard, my therapist.

Gratitude for Helping: 2

Someone recently wrote to me about a situation they were deeply concerned about. I’ll keep the details vague, but for context: they suspected that a child was being sexually abused. They had correctly identified the warning signs and reached out to me, knowing my own history of childhood sexual abuse.

I answered honestly but wanted to end on whatever positive note I could truthfully offer. So I thought carefully, asking myself what hope or optimism I could provide without minimizing the gravity of their concern. This is what I said:

“It is probably impossible for me to exaggerate how deeply and profoundly it fucks a kid up to feel responsible for something like this.

I’ve been in therapy with a very good therapist for a very long time, and I’m only able to fully believe that it wasn’t my fault part of the time. Rationally, I know it wasn’t my fault. I can accept that as true all the time. But what the mind knows and what feels or seems true are often very different.

This struggle continues despite the fact that I’m a high-IQ adult capable of solving extremely complex problems. It’s a lifelong problem—but it doesn’t have to be a life-derailing one. It can even become a gift in some ways, though it’s taken me years to develop that perspective.

I understand on a visceral level how something can be rationally, experientially, and obviously true while every fiber of your being tells you it’s false. In the world we live in, having that kind of internal conflict can be a powerfully helpful experience. It helps me navigate the world and make sense of things in a way most people can’t.”

I was honest with them, but I also wanted to acknowledge the complexities of my own feelings about the past.

I would be lying if I said I was grateful for having had an outlier-bad childhood. I’m not. There are still days when I’d probably sign a contract to end my life ten years early for just a handful of memories of parental love, pride, nurturing, or even just being liked as a little kid.

But I am grateful for the people in my life now. For my therapist, whose wisdom and skill are beyond measure. For my friends, who know the real me—and love me anyway. When I think about the six people who know me best, I realize that I’d be lottery-win levels of lucky to have just one of them.

I got them all.

Everything in life has tradeoffs. I didn’t get a choice about what happened to me as a child. But as an adult, I get to have some of the best people on the planet in my circle.

And for that, I’m grateful.

Gratitude for Being Helped: 2

I have the best friends in the world—better friends than I deserve. One of them has an encyclopedic knowledge of television and movies. Because I grew up isolated from mainstream American culture, he’s been catching me up for years, watching things with me and filling in the gaps.

My remedial American culture education has been wonderful in every way, not least because of all the jokes and memes I finally understand.

This year, we watched Mr. Robot. I highly recommend it to anyone with a trauma history—but only if you’re ready to be triggered. Personally, I found the triggers helpful, giving me a chance to integrate my own insights about trauma and the world through the story’s lens. But your mileage may vary.

We finished the show about a month before my birthday.

My birthday is incredibly important to me. I go all-out for other people’s birthdays, partly to show them how much I love them. But there’s a deeper reason: what my birthday means to me.

I came as close to suicide as someone can without succeeding. My birthday feels like a declaration that it’s okay I’m still here.

It feels like permission to be happy to be alive.

I don’t expect that to make sense to most people. But if you’ve ever tasted gun oil because you were that close to checking out, you might understand. If you don’t, good for you. Just trust me.

That’s what my birthday means to me. And that’s why I want my friends to feel the same joy on their birthdays: to let them know I’m just as happy they’re here as I am grateful to still be here.

For my birthday, my “cultural studies professor” friend gave me a signed script from Mr. Robot.

I can’t count how many times I’ve looked at it, smiled, and felt that rush of my birthday-permission-to-exist feeling.

I am grateful.

Gratitude for Struggle: 2

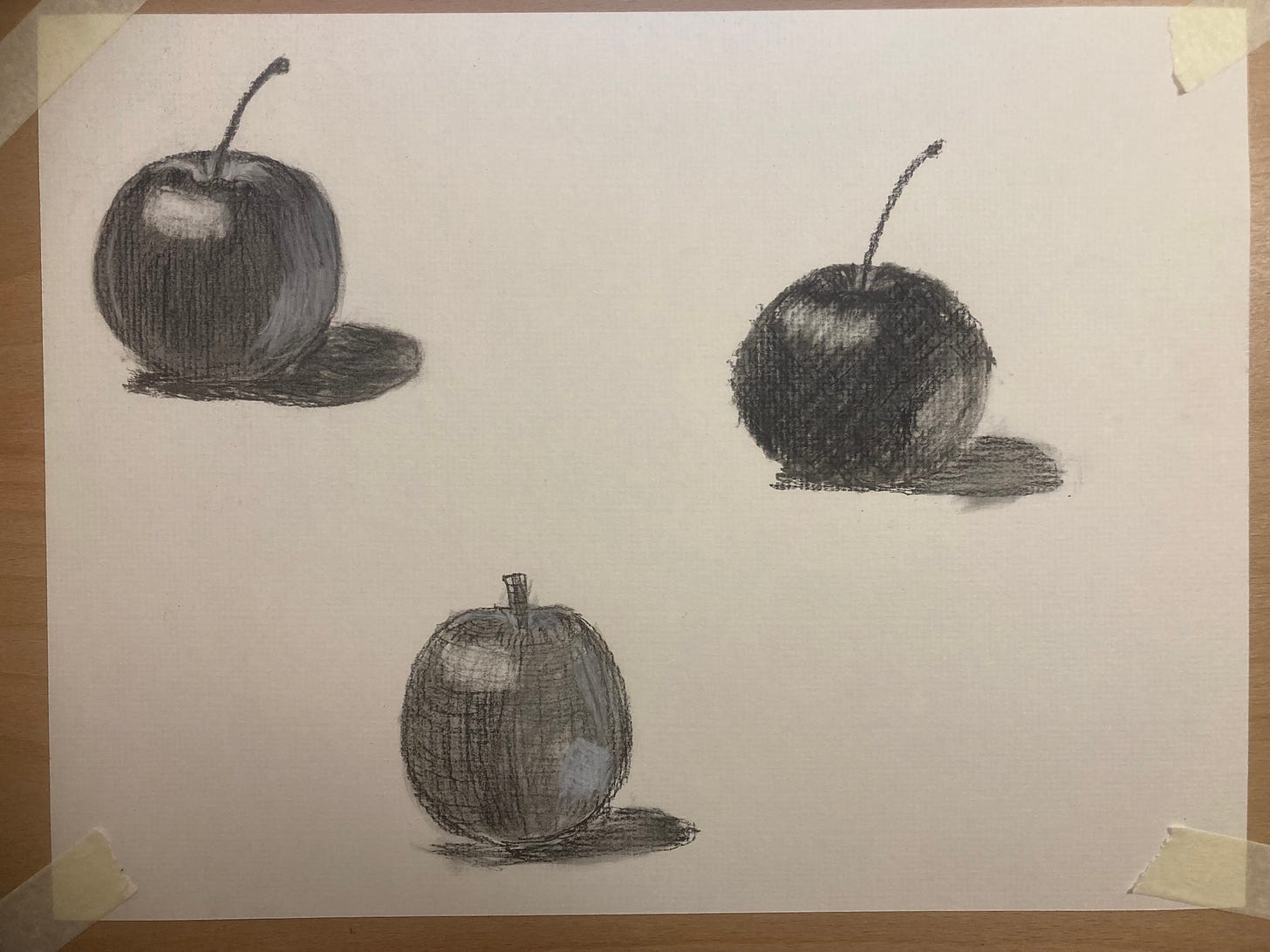

I’m pretty good at drawing. I taught myself, so my skills are wildly uneven, but overall — I’m not bad.

You can tell this is James Lindsay.

And you can tell that this is a kerosene lamp.

And this is a pretty good rendering of a guitar.

Here’s a post where I talk about drawing, including some tips and advice for the autodidact.

Now, let me tell you a hilariously stupid—but true—story.

I taught myself to draw in pencil for one reason only: I was too scared to let myself try drawing in charcoal.

Charcoal has always been my first love in art. I’ve adored it for as long as I can remember. But I loved it so much that I couldn’t bear to try. I couldn’t even admit to myself that I was avoiding it.

I wanted to be good at it so badly that the thought of the learning curve—the discomfort of sucking at something for a long time before you’ve practiced enough to not suck—was more than I could handle.

I figured this out in therapy, during a long conversation about the aesthetics of Vermont in winter and why that particular beauty is one of the rare things in my life that brings me mindful presence—true happiness, peace, and joy.

I don’t regret the time I spent avoiding charcoal. Regret doesn’t serve me, and the tradeoff was that I developed a high level of skill with pencil—a skill that’s transferable anyway.

But now? I’m drawing in charcoal. And I love it even more than I thought I would.

Gratitude for Helping Myself

A few days ago, I stumbled across something that has noticeably improved my sleep. Not as dramatically as the help I’ve already mentioned, but enough to make a difference.

I had ordered a new comforter for my bed, which was icy cold from sitting on the porch when I brought the Amazon box inside. Wanting to warm it up quickly, I made up my bed with it right away and turned the mattress heater up to 10, setting the timer to turn off just before bedtime.

I use the heater every night in winter. Around 7:30 p.m., I typically turn my apartment’s thermostat down to 60 so it gets chilly, making the contrast of a heated mattress especially cozy and comforting.

On a whim—and mostly to amuse myself—I tucked my teddy bear, Liam, into bed. I arranged him under the covers, propped the pillows around him like he was a toddler settling in for a nap, and couldn’t help laughing. It was a cute image: his dark fur contrasted perfectly with the bright red of my Christmas decor, and I enjoyed the aesthetic sweetness of it.

To be clear, I am not delusional or in any way convinced my teddy bear is real; no one needs to worry about that. It was just a moment of whimsy that made me smile.

That night, I slept shockingly well. Liam’s fur was toasty warm, and curling up with him was more comforting than it had ever been before.

Needless to say, I’ll be repeating this all winter long.

Gratitude for You, The Reader

I am grateful for the opportunity to write for an audience. While I write primarily to clarify my own thoughts, there’s something deeply satisfying and edifying about being read.

The money from paid subscriptions goes toward paying down my student loans, which means that owning a home someday isn’t just a pipe dream. That’s not something many renters can say these days, and I am profoundly grateful to be one of the few who can.

Happy Thanksgiving, y’all.

This was a post that would normally be behind my paywall as part of my creative writing series, wherein I take risks, post photo essays, review Woke books to mock them viciously, post writing experiments, and tell personal stories. In the spirit of Thanksgiving this one is free for all readers. Paid subscribers have access to my series on How to Not Suck at Math, as well as comments when they’re turned on (weekends for now; weekday comments will return when I’m more settled into my new job). If you enjoy it, there’s a Black Friday sale on paid subscriptions.

I will include your new job and your progress in the things that I am thankful for in my nighttime prayer. Have no idea whether that is positive support for you or not, but always finding something to be thankful for as each day ends is very positive therapeutically for me. Best wishes for your continued progress.

Last Monday I attended a charity gala for an organization started a few years ago by a friend and truly amazing woman, Darcy Olson. It is the Center for the Rights of Abused Children. It was created after her initial experience with the foster care system, as you may be aware, often a procedural nightmare where the “rights” of the children involved are totally subservient to the ideas of even the best meaning bureaucrats and judges, who unfortunately are outnumbered by the pretty tyrants or clueless functionaries. Darcy has made incredible in improving the system strides in improving the system and obtaining recognition for the legal rights of the kids involved. Her efforts have drawn nationwide recognition since the founding of the Center in AZ, and both a description of their work and some case studies are on their website if any of your readers are interested. She herself has fostered 10 children and adopted 4 , the oldest girl ( a 7th grader) spoke at the event and the attendees were incredibly impressed. She followed several other speakers, including the wonderfully blunt and very insightful Tyrus, whose childhood story and foster care experience ( of which I was totally unaware) make his current achievements even more impressive.

I mention this because in addition to being a cause that is worth supporting. If any of your Substack readers are aware of foster or abused children ( such as the one mentioned in this Substack posting) the Center now has a presence in many states and many lawyers who work pro bono or if their expenses are covers and may be either able to provide an introduction to those children in need or alternatively at least inform them of their rights and help put them in touch with an organization who could support them.

Again, best wishes in your continued journey from someone who in the early years of my life was both a math nerd and a bookworm, and while I left the actuarial profession at age 26 after my midlife crisis ( now 82 and very blessed and still continuing to learn and improve) I am still much more comfortable when alone or with small groups of good friends who indulge those tendencies.

It is always encouraging to read about times of extra-horizonation, such as where one struggles up the barrier dune at an unfamiliar beach to be greeted at the top with a sweeping vista of a massive bay; or when driving in the mountains and a narrow pass falls away to reveal a broad valley. (I suppose that says more about my psychology than yours, since, after thinking about it, I can imagine someone recoiling from the sudden openness. Still, I hope the sense of light-hearted optimism comes through.) I hope you write about the differences between drawing with charcoal and with pencil.