Comments for paid subs will open on Wednesday afternoon, November 27, when my workweek ends. They will then be open over the long weekend. I apologize for the annoyance, but I’m still acclimating to a challenging new job and this is helpful to me during my learning curve.

In the West, nearly all of us lead lidless lives: lives where emotional containment is not available to us in helpful, meaningful ways.

And we, both individually and as a people, desperately need emotional containers. The best sort of containers are proper outlets — places where emotions are meant to be directed, and where they provide helpful fuel to achieve positive aims.

Men often lack outlets for emotions like anger, aggression, and competitiveness, which can lead to destructive outcomes, for themselves and their families as well as society, when uncontained.

Women, on the other hand, frequently have too many outlets for emotions like nurturing, empathy, and sympathy, which can also lead to harmful consequences when unchecked — a reality we see all around us as Woke captures more and more institutions.

Yes, of course, men experience emotions like compassion, empathy, nurturing, and sympathy, just as women experience anger, aggression, and competitiveness.

I am a woman who owns zero dresses or skirts, last wore makeup in 2019, is contemplating a tattoo of Euler’s identity, and works coding all day. I require zero reminders that sex-based stereotypes are just that—stereotypes.

No one adheres to them perfectly, and many of us defy them entirely. This is not in doubt and the notion requires no defense.

Having said this, there will be no more caveats or “not alls” — if you need more, you’ll have to supply your own.

Sex-based stereotypes, like all stereotypes, exist for a reason, and the realities they are based on matter. The lack of containment is profoundly damaging, and on average, the damage caused relates to sex-typical emotional patterns.

This requires a lot of unpacking, so here’s a story that well illustrates my thesis.

The Addicts Who Live At The ATM

A little over a year ago, my friend

1 had a scary experience at an ATM in downtown Burlington, where he films his show. Downtown Burlington has become a progressive shithole — I mean that literally, as in “a place where avoiding human feces is a necessary skill” — which I’ve written about, and I had been rattled by aggressive homeless men a few times prior to Josh’s experience. But nothing terrible had happened, and it is truly wonderful fun to hang out at the studio, so I was still doing it from time to time.After Josh’s experience, we talked it over and decided that I wouldn’t come to the studio anymore, unless we went to great pains in advance to arrange for him or Kevin to meet me at the parking garage and escort me to and from the studio.

Josh and I talked about it, openly and bluntly, and that was good. It required zero courage because our conversations rarely elicit fear, and when they do, we are able to own that. Because we can say “I’m nervous about talking to you about (topic) and am afraid of how you’ll react,” we can talk about anything. That dynamic, plus the many things we have in common with each other and almost no one else, means that we can say things to each other that we’d say to basically nobody else. So a blunt, fully-without-caveats discussion about the state of Burlington’s downtown was something we easily had, and it helped.

It helped me a lot, and I think it helped him, too.

But Josh and I can do that for a particular reason: a reason that is either in very short supply or simply no longer present for most people—on any topic that is even politics-adjacent.

(Which is almost everything.)

Josh and I are able to be, in many important respects, emotional containers for each other.

I will explain my thinking here at length, but first I need to give the context: our national character and an idea we’ve taken too far.

America Is A 13-Year-Old With Bad Parents

America is a country of profoundly unhealthy extremes. We pendulum-swing in ways that would warrant a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder in an individual.

We are the people who went from chattel slavery to race-based affirmative action in medical school admissions in 150 years, a historical eyeblink.

We elect Jimmy Carter, then Ronald Reagan. We elect Barack Obama, then Donald Trump. We go from 1984 — a 49-state legitimate landslide by any definition—to our current condition, where any election that isn’t razor-thin, basically any situation where a definitive result is clear on Election Night, constitutes a “landslide”.

One way this national character manifests concretely is in the extremes of our wealth inequality. We have billionaires whose net worth surpass the GDP of entire countries, yet something like half of Americans couldn’t cover an unexpected $400 expense without going into debt. I’m not commenting on the morality of that situation, just its extremity.

Another way this manifests: we have vacillated between puritanical strictness and hedonistic indulgence since our founding. Prohibition and the unrestrained party-and-drug culture of the 1970s and 1980s both existed in a time frame so short that someone born during the former wouldn’t even be 60 when the latter started winding down.

The same nation that, in many red states, teaches abstinence-only sex education is also home to some of the most sensationalized media, hyper-sexualized advertising, and industries profiting off vice.

We are home to both the rural South — where public schools sometimes have “See You At the Pole” events with more students attending than not — as well as Las Vegas, where every vice is legal and celebrated.

This dynamic is part of our national character, or lack thereof.

It is also counterproductive, childish, and profoundly destructive.

In practice, it makes us most like a moody 13-year-old with terrible parents — parents who have left their kid home with an open liquor cabinet, a well-stocked arsenal, and access to unlimited cash.

This pendulum-swinging between extremes creates a nation that struggles with balance, moderation, and maturity. Given how young we are, as a country, this is perhaps understandable.

But we really, really need to start growing up a bit faster.

The Personal Is Political

The idea that “the personal is political” is probably one of the most destructive ways that our national character of extremes has harmed us.

The original arrangement of America, a laboratory of the states where divided powers competed against each other, slowly became more and more centralized, especially after the Civil War. Income tax, direct election of senators, and the prohibition of alcohol were all steps along this road.

Thus, we were fully primed to take the idea that “the personal is political” and, true to our character, go way too goddamn far with it.

Though this idea is much older than feminism, the notion that “the personal is political” came into full fruition during second-wave feminism, critiquing the generally held belief that there was, or should be, a strong divide between the private and public spheres.

This was absolutely a needed correction in some respects: the idea that domestic violence or child sexual abuse was a strictly family matter was evil, morally wrong, and the source of unnecessary suffering. Child sexual abuse used to be called “incest” specifically to minimize it, not simply to clarify that the rapist was a relative of the victim. Several states have had to change their laws to ensure that sexual crimes against children would be prosecuted appropriately, since criminal penalties for incest were much more lenient than criminal penalties for sexual abuse in general.

The norm that once existed, the belief that violence against family members was a private matter only, was a terrible norm. It facilitated life-ruining trauma and emboldened monsters. Evil people felt free to do things at home that would be criminal, and result in incarceration, if done to strangers, knowing that the cops would call it a “family matter” if they were notified at all.2

But in classic American style, we over-corrected. We didn’t take it to a sane level, where violence and sexual abuse were taken seriously at all times—whether in the home or not—and then stop.

We took it to a nutty, absurd, truly sanity-threatening place.

We made everything political.

The same nation that over-corrected on racism—I am repeating myself because I want you to think about how extreme this is—going from chattel slavery to race-based affirmative action in medical school admissions in 150 years — went so far with this idea that when Wokeness arrived, we were ready.

The foundation had been laid, the house had been built and furnished, and utter insanity had already filled out a change-of-address card to live there.

Wokeness sees absolutely everything through the lens of power dynamics, and does so with utter thoroughness. Woke notions of power dynamics have strict oppressor/oppressed assignments based on immutable characteristics, and set up Kafka traps.

One I remember from a class discussion: a black customer and a white customer enter a store simultaneously. If the clerk waits on the black customer first, it’s evidence of racism — fear that the black customer will steal if let alone. If the clerk waits on the white customer first, it’s evidence of racism — taking care of the white person’s needs first. The discussion revolved around how white people didn’t deserve to have an “out” since the black person would regard it as racism either way, so our fragile white feelings needed to take a back seat.

It is hard to imagine a more extreme situation than one where a binary choice is presented — wait on this customer first, or that one — and both have an accepted racist interpretation.

Returning to my story — what does “the personal is political” have to do with the need for emotional containment?

Containers Really Matter

Let’s imagine what happened to Josh—being scared by aggressive homeless people at an ATM and put in reasonable fear of being robbed and assaulted—in a vacuum.

Before every single thing became political, a man who had that experience could talk about it, and thus process it. He could talk about it to his father, brother, or guy friends, perhaps framing it as being glad he didn’t have to fight (if he didn’t want to admit, in front of other men, to being scared).

He could talk about it to his wife, girlfriend, sister, or female friends if he wanted sympathy, empathy, to have his feelings of fear validated, or to have his masculinity affirmed — to hear something like “I’m so glad it didn’t get violent, but if it had, I’m sure you could’ve handled it.”

Before every single thing became political, a woman who had that experience could talk about it, and thus process it. She could talk about it to her husband, boyfriend, father, brother, or guy friends if she wanted practical reassurance — promises of the “from now on I will go with you anytime you want and protect you” variety.

She could talk about it to her mother, sister, or female friends if she wanted to have her feelings validated, to hear “Oh My God, are you ok? I would’ve been so scared!” followed by a series of ideas for self-care in the wake of a difficult experience, or a long discussion of how scary the world can be, how challenging it can be to know when to trust your bodily fear signals and when to make yourself bravely ignore them.

This is no longer the case for many of us. These options to contain, through conversation, the emotions of any difficult experience that is even remotely interpretable as political no longer exist for anyone who must protect himself or herself against the perception of being right-wing.

No matter how extreme the situation — even dodging literal piles of human shit with small children in tow — complaining about the danger posed by homeless addicts in public spaces is now coded right-wing.

I see this constantly in my state. Anyone who expresses fear or discomfort about the state of downtown Burlington is accused of wanting the homeless locked up in concentration camps, of histrionics, or—worse of all—of loving the Bad Orange Man.

The idea that dodging needles, aggressive panhandlers, and piles of human shit in a formerly picturesque downtown represents a tragedy is mocked in all left-wing-coded spaces, which is all public spaces here.

I could give dozens of examples of this dynamic, but here is just one:

, a host from The Young Turks (a leftie network), was sexually assaulted by homeless people. When she talked about it, she was viciously attacked by other lefties and accused of being a “secret right winger.”A woman simply speaking the truth of her experience of sexual assault—something that lefties pretend to prioritize—was immediately declared evidence of right wingery because the perpetrators were in a sacred caste.3

A Model of Friends As Good Containers

When the incident at the ATM happened, Josh called me shortly thereafter.

In that conversation, he and I were containers for each other — for our respective emotions, opinions, and process of integrating this experience into our decisions going forward.

What do I mean by that? How were we containers?

If my memory serves, Josh ranted angrily about how scary it was, how wasteful, unnecessary, and ridiculous it was that a beautiful little town like Burlington has turned into a progressive shithole, and how frustrating he found it.

And I remember telling him that I was sure he could’ve handled it—and that I was very, very glad he didn’t have to. Josh is quick and strong, and I don’t doubt that, fueled by adrenaline, he could do real damage in any fair fight. But he was outnumbered nine-to-one and that is not a call from the ER that I ever want to get.

I also remember feeling moved, relieved, and comforted that he was concerned about my welfare so readily — that one of the first things he thought about was protecting me from going through something similar. I hope I told him that.

Josh and I both had emotions that were relevant to our status as Vermonters, as friends, and as survivors of serious trauma. Our home is a Mecca for addicts, who are being enabled and slowly murdered by the taxpayers — including us — who facilitate their slow suicide. And we recognize that many of those people have a lot in common with us, which makes this an emotionally complex thing for each of us to process. We are both about as lucky as survivors of long-term child abuse get, and we know that.

This made both of us feel a variety of emotions, but mostly — it made Josh angry, and it made me sad.

Yes, I am pointing out that despite both of us being atypical for our sexes — Josh is an obviously gay man, and I am a woman with mostly male-typical interests — we had sex-typical emotions.

Josh was mostly angry and frustrated — at his inability to take up a winnable fight, win it, and end the injustice of the streets being made unsafe for taxpaying citizens with legitimate business to conduct.

I was mostly scared — that my friend had come so close to something dangerous happening — and saddened by fresh evidence that the dangers of the world must cause me to either limit myself in a way that is extreme for women in the first world, like avoiding shopping downtown, or put myself at risk.

I was also comforted, grateful that my good friend thought about me and my safety, and volunteered to protect me in future situations of the danger he had experienced.

In that conversation, I was a container for Josh’s anger and frustration.

And Josh was a container for my fear, sadness, and confusion — which was rooted, in large part, in frustration that the people causing the problem downtown are beyond help.

They are beyond the point where caring, help, charity, or expressions of caring, do anything other than hurt them. Which leaves my desire to care and help with nowhere to go.

We were containers for each other, we decided how to handle it going forward, and then it was over — no more need for processing, reflection, rumination, or other focus.

I have noticed, with gratitude, that we do this a lot for each other. It’s not uncommon for me to help him find a little more empathy, usually by widening his perspective. In so doing, I think I help him channel his anger more productively than he might do on his own, at least some of the time.

And it’s even more common for him to rein in my tendency to panic, asking me if this or that is really a huge problem right now, or to buck me up and remind me of the many times—in my life, his life, and the myriad examples history offers us—when suffering was the route to improvement, change, and growth.

He definitely helps me channel my empathy, nurturing, and desire to take care of people more productively than I would manage on my own.

I am using this personal example of a male/female friendship in my own life in part because so many of my readers also watch his show, and that will make the example relatable.

But also because these patterns are real, and they matter. They appear all the time, much more consistently than many of us are comfortable admitting.

They appear regularly and predictably, including in men who are as atypical as Josh, a man so gay that it’s obvious from miles away, and in women as atypical as me, a woman who budgets her cognitive energy to get the maximum lines of code possible in a day and regularly prays — just in case anyone is listening — to live long enough to see the Twin Primes Conjecture proven.4

When There Are No Containers

The societal consequences of uncontained emotion are all around us. Better chroniclers than me, including

, have gone into this in depth. His series is a brilliant and thorough investigation of how the excesses of female-typical emotional patterns have wreaked havoc on Western institutions.This is a problem that sometimes gets overlooked because consequences of uncontained male-typical emotional patterns are dangerous in much more obvious ways — physical violence, rampant procreation followed by abandonment of the children, crime, and the like.

Also, we have a tendency, as a society, not to recognize male-typical emotion as emotion. Anger is an emotion. Even when it’s appropriate and justified, it’s still an emotion, as is competitiveness. This tendency towards failing to recognize male-typical emotions as being emotions sometimes manifests hilariously, as when I got a message from a male reader that called me the c word three times, expressed hope that I would die in a fire, and suggested that, absent said fire, I consider commiting suicide — because he was tired of seeing people quoting from my overly emotional takes on the world.

In the wake of the election, many leftist women took to TikTok to express their feelings, and those examples of histrionics have been mocked endlessly in the last couple of weeks. The most creative and interesting version of this can be found on the Twitter feed of

, by the way.5Leftist male emotion is rarely examined, but I got a good look at it over the weekend. Substack Notes has recently become overrun with refugees from Twitter. In the wake of the election, flouncing away from Twitter has become the virtue signal du jour, as the brilliant

has chronicled.Some of these people are angry leftist men who regard Trump voters as the enemy they seek to destroy. Without any proper outlets to contain their emotions of anger, aggression, and competition, including their anger at having lost the recent vote-counting competition, they are turning toxic and scary.

During my weekend stint on Notes — I stay off it during the workweek —I didn’t see any explicit calls for corrective rape of female Trump voters, but I saw plenty of Notes expressing vengeful fantasies that stopped just short of that.

These men absolutely believe that there is no limit to the punishment that the stupid bitches who didn’t have the sense to vote with them, to virtuously elect the brown woman candidate, deserve.

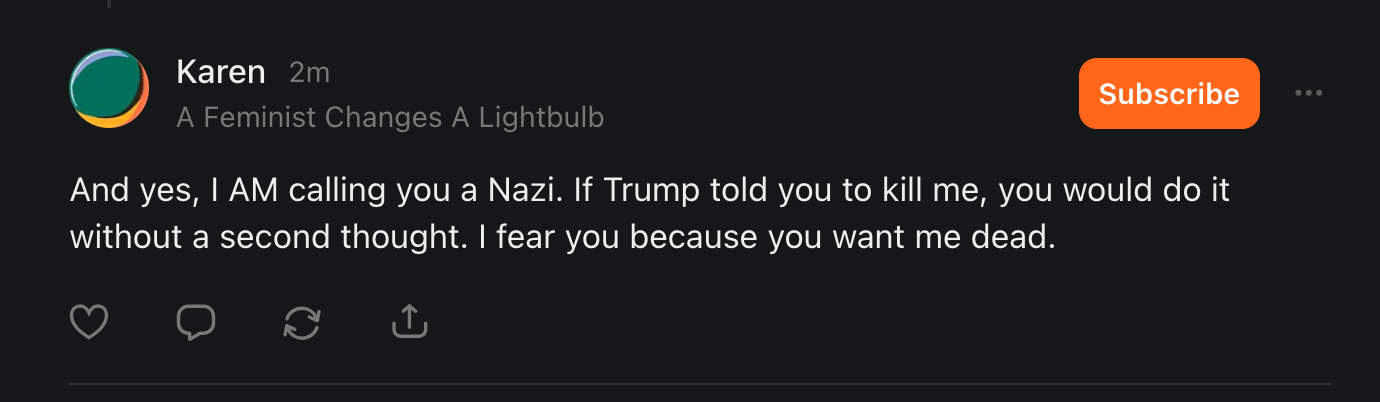

Likewise, some of the leftist women who’ve fled to Notes lack any containers at all for their fear, either for themselves or those they regard as marginalized. I was in the right mood to explore this a bit, and grabbed screenshots of a conversation with one of them:

Examples of leftist male-typical anger also abound on another issue — that of the transgender agenda. Search Twitter for “TERF,” which used to mean “Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist” but is now just a catch-all term that means “woman I’d like to call the c word but am not quite brave enough to do so in public yet.”

Leftist men, and not just the ones who masquerade as women, regularly fantasize, often typing with one hand6 about punching TERFs, which is the morally virtuous way they’re allowed to channel their anger at women more generally: by focusing it on the bad, mean women who disagree with them.

Wider Relevance: We All Need Containers

The conversation Josh and I had after his experience at the ATM was possible for one reason only — Josh and I share the political view that the literal shithole status of downtown Burlington is unacceptable, and we agree with each other about the causes behind it.

We had no fear of discussing it with each other because our views, while coded right-wing, were known to each other and we had no fear of looking like a right-winger to each other. Neither of us regards that as a moral indictment; thus, neither of us feels obligated to make sure the other doesn’t think of us as a right-winger.

People who can’t afford to risk looking like a right-winger on any topic — from dangerous homeless addicts downtown to the invasion at the Southern border, from the perils of “harm reduction” policies to the unintended consequences of affirmative action in formerly elite institutions — have to take their emotions and direct them somewhere other than where they’re meant to go: into a conversation where they can be processed.

Without containers, the splashing becomes disastrous, the excesses become toxic, and we end up where we are: in a world where feminized-beyond-containment leaders, desperate to prevent suffering at any cost, instantiate Woke bullshit and comforting lies into our laws and norms, providing addicts with clean needles to help them kill themselves; and masculinized-beyond-containment leaders engage in endless cycles of performative brinkmanship, fueling wars and doing insanely stupid things like risking World War 3 during a lame duck period, creating a mess that can only weaken the US no matter how the incoming administration decides to handle it.

We, as individuals and as a people, are drowning in the consequences of these extremes—lives without lids, emotions without containers.

The solution isn’t to strip away the traits we’ve labeled masculine or feminine but to cultivate meaningful, constructive ways to channel them, recognizing that balance is not the enemy of progress but its foundation.

We need to cultivate containers again. Some will insist this means returning to the norms of the 1950s, but that is both impossible and undesirable.

That would represent yet another American pendulum swing — and, worryingly, one from which the inevitable reaction would probably be unrecoverable. (Imagine a society that went even more feminized and Woke than we already are.)

Humans are the most adaptable creatures evolution has ever produced, and we are capable of growth and change.

Americans mostly do change, so far, like an unsupervised 13-year-old with drugs, guns, and money.

But we don’t have to keep up the pendulum-swinging.

We’re allowed to grow up.

And God, I hope we do.

Soon.

Paid subscriptions go to helping me pay off my student loans, and I’m offering a Black Friday sale at this link.

Josh’s podcast, Disaffected, is excellent, as is his Substack, and you should give both a try.

Here’s a link to just one case that was part of the nationwide movement that eventually resulted in changes in how police respond to domestic violence calls, but only after many years of preventable suffering.

The Twin Primes Conjecture is one of the oldest unsolved problems in number theory and it’s the coolest thing ever and if you aren’t obsessed by it do you even math, bro?

Her social media critiques of these videos, from her perspective as a master filmmaker, is hilarious. She posts them on her Twitter account.

I said what I said. Yes, right-wingers do it too; over the summer I spent weeks in therapy dealing with night terrors caused by one of the right-wing versions of this that went Notes-viral. But the difference is: nobody, certainly nobody in a powerful institution, regards that as virtuous masculinity.

I'm pleasantly surprised to find you read Lorenzo - we've connected recently on S - from him I encountered the expression "emotional incontinence" to describe excessive responses. I think there is a collective dynamic to this. One of the interesting things I've noticed is a behaviour little children engage in - its really funny when you are aware of it and notice an episode taking place.

I've observed that children don't react spontaneously to a minor accident - like tripping & falling over on their butt without first taking a quick glance at the parent - if the parent shows frowny response the child responds by going to tears; when the parent starts laughing at the clumsy little one the child responds alike and starts giggling & no harm is done.

Adult political responses may well work as a parallel process (or maybe even the identical one?). That is people gauge the social norm (ie rage at anyone breaking a social commandment) then reply with the woke response. Progressives behave like this because they receive a "social license" for it. If the majority withdrew the license they would likely respond by suppressing this kidult behaviour.

Mental and emotional containers as an allegory for self discipline and observing behavioral norms (or a lack thereof anyway)? Sounds good to me and your discussions are quite relevant.

That lady Karen needs help and right away or something awful is going to happen to her. No one should be afraid of the truth and the truth is no one wants to hurt her, not for political or ideological reasons anyway.

I think the malign confluence of the Internet, where people can choose to anonymous and everywhere; breakdown of manners exacerbated by social media, overly partisan politics and COVID restrictions; growing emotional immaturity; as well as truly insane delusions masquerading as “truth” (that no one may question? 🤢) has put us in a bad place.

Additionally, I think a good many of these folks apparently lead unfulfilling lives and have WAY too much time on their hands. I posit that those of us busy with filling jobs or working hard to make a living do not engage in this behavior. Worse, I fear many Americans have a very poor grasp of history and do not understand how hard it really is to build and maintain a complex civilization. Anarchy, chaos and civil war would NOT be better folks!

Holly, you are so right that we desperately need to grow up as individuals and as a nation. Perhaps if those most afflicted would back away from social media, take some deep breaths, go for some long walks in the woods and reconnect with reality it might help.