This post has a ton of pictures and is also longer than most email clients can handle, so you may want to read it at the Substack website by clicking on the title above.

Edition 5 of Monday Morning Love

This is my series for starting each week of on a note of positivity! I write about something I love and publish it first thing Monday Morning, in an attempt to start the week off on a positive note.

Previous editions have covered a favorite childhood book series, The Great Brain; building things with LEGO; the branch of mathematics known as number theory; and drawing, a start-to-finish how-to post for creating a finished piece.

I’m not going to put these behind the paywall, but if it motivates anyone to become a paid subscriber, my student loan balance would appreciate dwindling a bit in your honor, and there’s a special deal at this link. Comments are open for paid subscribers.

Edition 5: I love reviewing books

Several internet forums, including DataLounge and several subsets of Twitter, have recently been discussing Their Troublesome Crush, a novel I reviewed last December. It is the Wokest novel I’ve ever read, and my review of it was one of the most successful posts in the history of this Substack.

I absolutely love reviewing books, which I usually reserve for paid subscribers. I am presently reading Math-Ish: Finding Creativity, Diversity, and Meaning in Mathematics, a book by Jo Boaler, the woman responsible for re-vamping the California math curriculum, and will review it for paid subscribers soon.

Given how important it is to me that kids be taught math (and not things that are vaguely Math-Ish), I suspect my review of that book is going to rival this one for snark. So, since this book is getting a lot of talk at the moment, I decided to give the free subscribers a peek behind the paywall. For today’s Monday Morning Love post, I decided to republish the book review. Enjoy!

This is a review of the Wokest novel I’ve ever read — indeed, the Wokest novel I’ve ever heard of. Here is how the Amazon order page describes it:

Don’t worry; I will explain every Woke term in that description as we go along.

I intended this to just be a funny snarkfest, but it turned into something much more than that: this novel is an almost perfect illustration of how the Woke believe everyone should live and relate to one another. Much of what I experienced being taught, in university, as the only correct and moral way to relate to others is exemplified in this story. This is the world that Wokies want. This is the world they will force on us if they get the chance.

And they don’t give a rat’s ass if we consent to it or not.

Religious Parallels

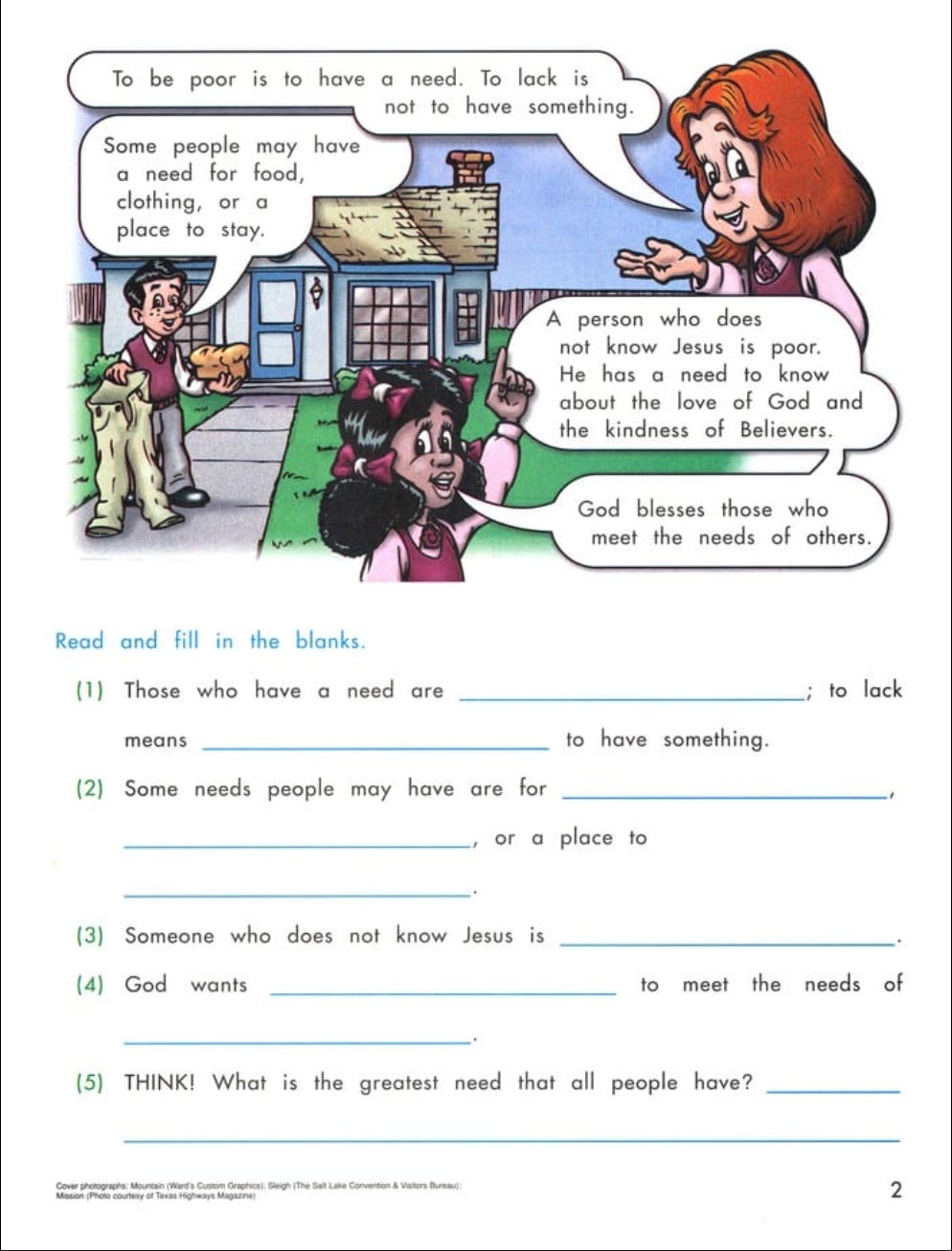

A Christian curriculum company called “School of Tomorrow” makes “educational” materials that I was forced to endure for a couple of years as a kid. The one benefit of the system—kids going at their own pace—is what made the church school I was in ultimately reject it. Several kids were so far ahead of their grade level that they were on pace to finish high school by age 12 or 13. The adults had no idea what they would do with us, then, so they ultimately switched from the ACE system to the A Beka curriculum, a different Christian one. We weren’t a bunch of child geniuses — the curriculum is just shitty. Here are two pages from a third grade “literature and creative writing” book:

The most memorable part of the curriculum is the comic strips in which they taught kids how to see the world. Most of it was shallow to the point of silliness, but some of it, like this 6-yr-old girl worrying (while clutching a doll) that she’s showing too much skin, is downright sick:

A 6-year-old who shows her knees and worries she’s showing too much skin needs a psychological evaluation for what the hell adult men in her life are doing and saying to her, STAT. Normalizing this worldview is tragic.

I kept thinking about these comic strips as I read the book. The comic strips were an illustrated version of the kind of Woke paragon this novel represents.

Now for the guide to Woke language and the characters:

What Those Woke Words Mean

Queer: this is a “reclaimed slur,” that once referred exclusively to homosexuals. Now it is used much more broadly, including by straight people who are desperate to gain some Woke street cred. It basically means “not heterosexual and/or cisgendered.” A normal straight couple that has missionary-position sex and makes babies can be “queer” if one of the members declares himself/herself non-binary.

Cisgender or “cis”: this means “not trans.” If you accept the reality that your genitalia and chromosomes determine your biological sex and you are not trying to force other people to pretend otherwise, you’re cisgender.

Non-binary: this is a self-identifier used by people who want to claim that they’re neither a man nor a woman. It is silly, stupid, shallow nonsense, and logically incoherent. Every non-binary person asserts the existence of two categories: the non-binary, like themselves, and the rest of us, who are binary — and thus both creates and participates in, a binary.

Polyamorous: from “many loves”, this term names a relationship structure that involves infidelity as a matter of course. Essentially cheating with permission, or at least awareness.

Metamour: your lover’s lover. The person that is sleeping with/involved with the person you are also sleeping with/involved with.

Demisexual: a person who does not experience sexual attraction or desire to have sexual relationships without first forming a close emotional bond. As my therapist said when I told him about this (it was taught as fact in one of my university courses), “When I was a boy, we had a different word for people like that. We called them, ‘women’.”

Demiromantic: the same as demisexual, only with “romantic attraction,” which Woke people seem to define as completely separate from sex — this “split track” notion is one we’ll return to.

Transman: a woman who identifies as a man and, if possible, has her breasts surgically removed and takes testosterone in order to mimic male secondary sex characteristics (beard, deepening of voice, redistribution of fat, etc.).

Submissive: someone who experiences sexual arousal/sexual pleasure from being dominated by another person, or physically hurt by another person.

Dominant: someone who experiences sexual arousal/sexual pleasure from dominating or physically hurting another person.

Switch: someone who engages in both submissive and dominant behaviors at different times.

Femme: roughly equivalent to “feminine,” essentially an adjective that asserts the person it’s applied to engages in stereotypical femininity, like makeup and girly clothing.

My Take on Some Relevant Issues

It’s important to reveal biases and perspectives that may affect a review, up front, so here are mine.

Childlike Coping Mechanisms

In the novel, nearly every character has childlike coping mechanisms for life stress, including meltdowns, temper tantrums, running away from stressful conversations, and desperately attempting to be patted on the head and told that he or she is a good boy/girl. I am going to critique this harshly, so it’s important to own my biases.

I think childlike coping mechanisms are fine, in limited ways that are not excessive and that are not imposed on other people. An example of what I mean: I can’t have a pet where I currently live. If I could, I’d be sleeping next to my dog, because I’d have one. But I can’t, so I sleep with a teddy bear who I got cute little hearing aids for:

This is a little silly, but it’s helpful, and I don’t impose it on anyone else.

I freely admit that I’m indulging an aspect of my own arrested development. I indulge it consciously and with self-awareness, and I do not expect anyone else to indulge it.

Representation

Between myself, my close friends, and children I’ve been employed to care for, I know quite a lot about managing a chronic shoulder injury, deafness/hearing loss, PTSD, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, POTS, and IBS. I sometimes write fiction in which a character must manage one of these conditions while engaging in the events of the story. I don’t do this out of some notion of “representation” being a virtuous way to reduce “oppression.” I think representation done performatively is silly and stupid and rarely makes for good reading. Rather, when I choose to give a character of my creation part of the complexity I know well from living in my physical body or paying attention to others who deal with their own physical challenges, I am attempting to make the character more fully realized. Fiction works best when the details seem real—and the details can best be made to seem real when some of the details are real, so either doing careful research or using aspects of the writer’s own experience is often a way to do “representation” well. In real life, characters have physical and psychological limits, injuries, and disabilities, and showing these well in fiction makes for good reading, reflecting the reality around us.

JK Rowling does this brilliantly in her detective series, where the main character is an amputee who must manage how much he uses his prosthetic limb. As I wrote in my review of one of her books:

Strike’s chronic injury was especially well-handled. Rowling handled this with such realism that I wonder if she has a previously undisclosed chronic injury, herself. At the bare minimum, she did excellent research. Strike has an ongoing calculus in the back of his mind, always weighing exactly how much he can use his stump before he has to rest. Under stress or in the heat of a moment when he seems to be getting close to a breakthrough in the case, Strike convinces himself that he can push himself and it’ll be fine. It’s never fine. Often when dealing with the consequences of having pushed himself beyond the limits imposed by a chronic injury, he wonders how he could’ve been so stupid. This was all so exactly like my own experience of living with a chronic injury that I was delighted to read it, and filed it away as a potential example for explaining life with my shoulder in the future.

So, as I hope is obvious, I am not reflexively against “representation” as such, just representation does badly, or as a sermon.

Coddling as Virtue

Friends aren’t therapists, and they shouldn’t try to be. But friends should also try to bring out the best in each other, and help each other grow. In the case of people with serious psychological difficulties, this can be tricky and something of a balancing act. It is encumbent on people with serious problems to understand themselves and their problems, and to minimize the effect of those problems on other people. But this isn’t always possible, and friends sometimes have to say things like, “I understand how anxious you feel, and if (whatever it is) was happening to me I’d probably feel just as anxious. But I can tell you that from the outside, your fear seems completely ridiculous. I do not think what you’re afraid of is likely to happen, not remotely likely” or “I understand why you feel an urge to act on (impulsive decision) right now, but do you really need to do it right now? Is it really urgent that you do this immediately, or are you just urgently trying to change how you feel?” This isn’t always easy, but just as a self-aware person knows when to respond to “Hey, can I call you?” with “I’m having a bad PTSD day. I can overcome it if you’re having an emergency and you really need me to, but if it’s not urgent, can we talk tomorrow?”, a real friend will hear some gentle pushback as an expression of concern, love, and respect.

Friends who reflexively coddle their friends—who never challenge, never push back, never point out that fears are overblown or that impulses shouldn’t always be acted upon—are not friends at all.

The Actual Review

Summary

Ernest is an autistic woman who identifies as a man. Nora is a woman who is aware she is a woman. Gideon is a woman who identifies as a man. Gideon is in a BDSM relationship with both of them. All three characters have serious psychological issues stemming from dysfunctional families, mental illness, addictions, and other tragic aspects of their lives. Rather than work towards health and normalcy, they all embrace their sicknesses and have turned them into core pieces of their identities. Gideon works out her rage on other people by physically abusing them with their consent. Ernest works out her self-loathing by volunteering to be physically abused by other people, to such a degree that at one point being caned (beaten on the bare backside with a thin, flexible rod) is described as a “reward.” All three characters are deeply confused about many things, and are unable to relate to each other or the world outside of Woke ideas, BDSM paradigms, and the overlap of both.

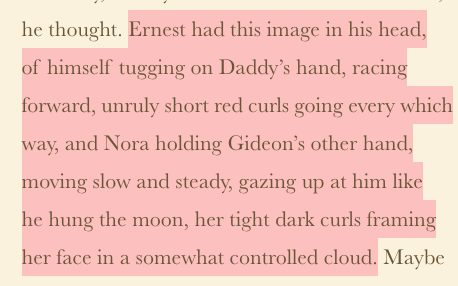

Ernest and Nora call Gideon “Daddy” and are both creepily childlike in their attempts to gain her approval. They are working on planning Gideon’s birthday party when they develop feelings for each other that are described as a “crush,” but in the weird Woke paradigm that splits sexual attraction apart from aesthetic attraction and romantic attraction, their relationship only involves physical abuse of Ernest at Nora’s hands, and does not involve sexual activity, so it’s more of an unusually dysfunctional friendship than what most readers will understand as a “relationship.” This “split attraction” model is core to Woke notions of relationships.

Just as anti-racism asserts that every human relationship involves racism: “The question is not ”did racism take place”? but rather “how did racism manifest in that situation?” this story finds Woke and BDSM power dynamics in absolutely everything.

The main story arc isn’t much of a story at all — it simply involves Ernest and Nora performatively virtue-signaling their Wokeness to each other as they, through negotiation and explicit communication, gradually move their relationship away from casual friends to a more fucked-up friendship than they had when they were just metamours, each “serving” their mutual friend, Gideon.

Throughout the book, they interact with many other characters who are Woke and/or into BDSM, have multiple mental illnesses and destructive coping mechanisms, and the performed normalization of these things is the only real story.

The Good, The Ugly, and The Terribly Bad

The Good

The book is competently written, with characters that stay in character. They have fully realized Woke worldviews, and they are absorbed in those worldviews at all times. There is only one typo and no issues of grammar, spelling, or other mechanics. If the author ever escapes from the Woke cult, he or she writes well enough to perhaps write a story that’s more than a Woke paragon.

The Ugly

The author’s entitlement is jaw-dropping, and his/her devotion to Woke is overwhelming. Consider that there are both pronouns for characters and instructions not to misgender characters in reviews (instructions I am quite obviously ignoring).

The Terribly Bad: Vaguely Pedophilic

The entire story has vaguely pedophilic overtones, making the whole thing creepy and gross from the start. Sexual experiences and thoughts are put into childlike terms in a way that’s stomach-turning.

Here’s the beginning of the story. Reminders: Ernest is a woman who identifies as a “boy,” Gideon is a woman who identifies as a dominant man, and Nora is a woman who knows she’s a woman. They’re all in their mid-30s or older.

Tell me this doesn’t sound like a little boy whose father has abandoned him fantasizing about his father coming back and taking him and his big sister on a trip to the park or to get ice cream or some such:

Over and over, Ernest (the point of view character) and other characters are described in disturbingly childish ways:

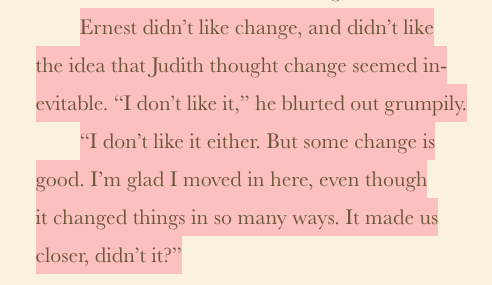

In this scene, another adult character is explaining to Ernest that change is inevitable in life. Doesnt this sound exactly like a babysitter explaining to a grumpy four-year-old that change is good, sometimes?

Ernest engages in self-harm via BDSM, having other people beat and injure her with her consent. She is unable to get “top surgery” (euphemism for a double mastectomy) because her obesity makes it too dangerous, but her joy in wearing a chest harness is described in, again, very childlike terms:

After a very mild social faux pas, Ernest has a meltdown and runs away, exactly the way that a young child who hasn’t been taught any emotional regulation skills at all might:

The Terribly Bad: Victimhood as Virtue

Just as fundamentalist Christian curriculum uses paragons of Christian virtue to illustrate how readers should think, so does this novel. Compare the comics and the novel passage below.

In this passage, Ernest is angsting over whether Nora, a diabetic, will want to taste-test cupcakes for Gideon’s birthday:

Notice that finding all possible angles of victimhood—searching for them, making sure that none are missed or forgotten—and embracing them, as well as positioning herself in the hierarchy correctly, are core to Ernest’s thought process. This is a demonstration of Woke virtue and of the correct way to be a friend to Nora: to look for and acknowledge all aspects of her victimhood.

In a later passage, Ernest, a woman who identifies as a man, suffers from gender dysphoria, a fancy term that means she doesn’t like her sexed body. Notice that the victimhood of surgeons having weight requirements for elective surgeries makes her an even victimer victim than other transmen, like the one she calls “Daddy”:

The Terribly Bad: Performative Representation

Ernest is described as autistic, but comes across more like a non-autistic person lecturing other non-autistic people about how to communicate with autistic people.

The Terribly Bad: Good People Coddle Their Friends

Here Nora implies that only people with “mental illness” can understand the notion of being “triggered,” which is flatly ridiculous. This is one of the many messages that good people coddle their friends at all times:

After the previously mentioned faux pas that sent Ernest into a meltdown from which she ran away, Nora coddles her at great length, including a paragon of demonstrating how Good People don’t just coddle their friends, they go to great lengths to get instructions on how to do so:

In the next scene, we learn that good people coddle their friends — even friends with whom they’ve got no romantic or sexual entanglement at all — by cuddling them the way one would a distraught child, but with fat acceptance pandering worked in. This scene was extra creepy to me because I used to do respite care for a foster family that was caring for a child who had extremely volatile emotional outbursts (related to the abuse that had put him in foster care in the first place) and this was very similar to how I would handle him if he was upset. “You look like you might want me to pick you up and put you in my lap and hug you for awhile. Is that what you want?” If he nodded yes, I would hold him that way, wait for him to calm down, and then praise him for having felt his feelings without yelling, throwing things, etc. But this was done on a chair, not a bed.

And he was five.

Gideon’s birthday party is set up to cater to her “depression flare.” Rather than being appreciative of many people putting in time and effort for her birthday party, she is set up with all kinds of barriers between her and the guests to keep them away. This catering is absurd. It would be more rational to cancel the party, but instead we get Woke notions of not “setting up an expectation to perform joy.”

The Terribly Bad: Power Dynamics as the Only Reality

Nora expresses disgust at being found attractive without her consent, which, as far as I can tell, is what she means by the word “fetishized.” The simplest act of human interaction is recast into oppressor/victim terms from the beginning.

This section made me nauseous. Everything is power dynamics to these Woke morons—everything. Serving tea to a friend who comes to visit is “submission.” I immediately thought of having friends over to dinner. The friend I see most often always likes to salt and pepper his food, and it always makes me smile to remember to put the shakers by his plate before we sit down. In the world of the Woke, this isn’t my being a thoughtful friend or a good hostess. This is “submission”.

Nora has a warm, comfortable home that is set up exactly how she likes it. I relate to this. At this moment, I am walking on an under-the-desk treadmill at a desk covered with LEGO flowers, on a desktop with multiple mathematical stickers on it. My home is set up to my aesthetic standards, too. But this can’t just be a case of a woman being her own homemaker. No, this too has to be about “power dynamics,” in this case the “dominance” of a woman who identifies as a “switch” — both dominant and submissive at different times.

One character has a “queer platonic partner,” which is a “non-romantic intimate partnership.” In other words, a close friend. But in the Woke world of everything being labeled and categorized according to power dynamics, this requires special nomenclature.

In a creative project, Ernest is encouraged to make a character she is writing “on the aromantic spectrum.” In Woke terminology, “demiromantic” (as defined at the beginning) is on a “spectrum” with no romantic feelings at all (someone who only engages with sex, without feelings getting involved — nothing unhealthy there!) at the other end of that spectrum.

The Terribly Bad: Woke Political Preaching as Undercurrent

One of the core Woke political notions is that homosexuality isn’t really a thing. They think that a gay man has a responsibility to express attraction to (or at least, willingness to consider dating) anyone who identifies as a man, even if that person is a woman taking tesosterone. And that a straight man has a responsibility to express attraction to (or at least, willingness to consider dating) anyone who identifies as a woman, even if that person has a penis and is a man wearing a dress. This is worked into the story in an eye-rolling way:

Nora (the woman in purple on the cover) is obese, but she’s not 900 pounds. So the section wherein she explains to Ernest why she feels comfortable (in her own home) reads like especially pathetic political pandering, this time to the “fat acceptance” movement:

The characters hold a seder for Passover, and Woke political pandering is mandatory, naturally:

Ernest even reads sick sexual shit on the Sabbath during a religiously motivated social media fast, because that makes sense in any world other than this one, where Woke political pandering is mandatory:

The “split attraction” model that breaks everyone into microcategories is so normalized in this world, and so stupid, and so sick:

One must always disclaimer when one enjoys something that isn’t totally Woke:

The Terribly Bad: Gross Sexism

Besides Ernest being “rewarded” by a beating and later by a session of being tied up and rendered helpless, neither of which I am going to post snippets of — consensual violence is still violence — naturally, Ernest and other female characters serve the “dominants” first, all of them male or playacting at being male.

And of course, Ernest is made giddy with happiness at the prospect of “getting” to make breakfast for everyone. What else do women find joy in, besides being beaten by men and cooking for men?

For comparison: more retrograde sex role crap, this time from the Christian curriculum.

Conclusion

Woke “art” is sermonizing horseshit, but I’m glad I read this. It affirmed for me that my memories of university are not hyperbolic or exaggerated. I really did understand how these people think the world works and what the world should look like.

To which I say the same thing I said on September 9, 2021, when the President of the United States told me, with contempt in his voice, to get my body penetrated with the medical instrument of his choosing because his patience was running thin:

No.

Fuck you.

I will not comply.

Other Book Reviews I’ve Written

I have reviewed Lionel Shriver’s newest novel,

‘s memoir, one of the JK Rowling mystery novels, a novel by Simon Edge, a memoir by , and a memoir by a North Korean defector. These are usually behind the paywall, so if you enjoy them, consider a paid subscription.

This review was one of the first posts of yours that I ever read. It's what prompted me to subscribe. I'm still astounded that this novel exists—and worse, that apparently there's an audience for it.

I feel like it peeled off the facade to reveal the kind of world the Woke not only live in, but the kind of world they want us ALL to live in. The creepy infantilization of adults (made worse because it's so sexual). The way it sounds like it's written for 6-year-olds, and then suddenly gets into physical abuse for sexual pleasure. The creepy obsession with disability, dysfunction, and building an identity out of pathology. The way the characters don't have personalities, but they have intersectionality and fetishes. The way they try to embrace, maximize, and glory in their illnesses and syndromes.

This is their world. This is how they believe Good People(TM) live and think. When woke and queer texts are presented in schools, this is what they are trying to turn the next generation into.

The sheer performative exhaustion of this kind of life blows me away. The pedophiliac, creepy, sexual dysfunction makes me nauseous. The metamorphasis of normal relationships and friendships into constant sexual, abusive, dysfunctional power-struggles just makes me sad.

This is their world. This is their utopia.