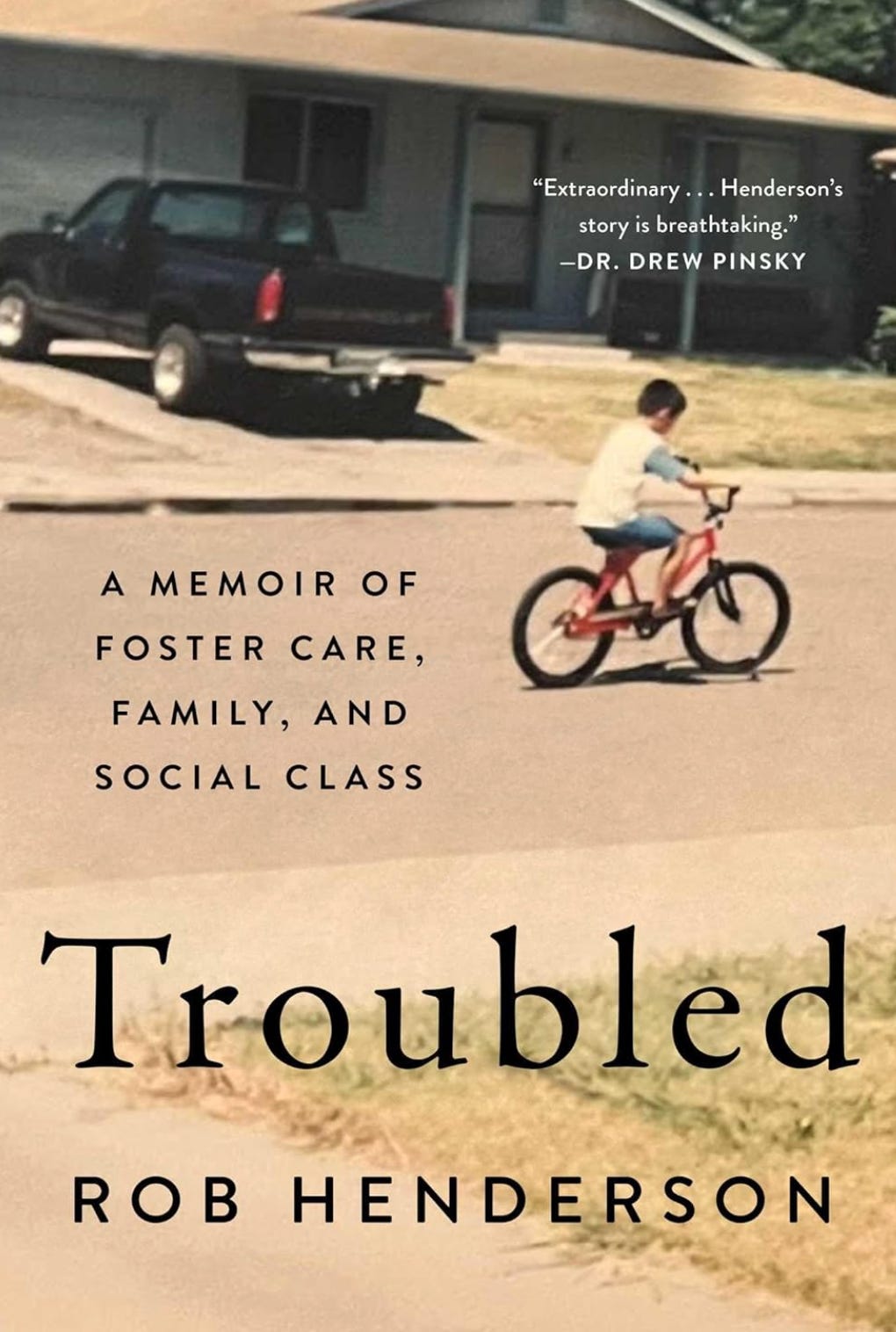

Because of my friendships with Bret Weinstein, Heather Heying, and James Lindsay, sometimes readers assume that I’m friends with all the influencers in the anti-Woke part of the internet. This is not true; Rob and I are not friends. Troubled will be released on February 20, 2024. Rob sent me an electronic copy because I emailed him via Substack to let him know that I was planning to review his book (which I had already ordered); that’s the only reason I got my hands on an advanced copy. Thus this review has no friend-bias, and all my priors are outlined below.

My Book Reviews

I review books regularly, including the Wokest novel I’ve ever read (complete with pronouns for the characters and instructions from the author not to misgender them in reviews!), a memoir of escaping North Korea, a memoir from Konstantin Kisin, a murder mystery by JK Rowling, and others.

If you used to read a lot but have lost the habit in our tech-addicted world, this essay about how I got my childhood reading habit back may help.

My Priors Going In

I have long admired Rob Henderson’s thinking, especially on two fronts:

His construct of “luxury beliefs”, which are beliefs that confer status on people of relative privilege while harming more unfortunate people. Crucially, privileged people rarely live by these espoused beliefs (they decry monogamous marriage as outdated and oppressive for women while rarely having children out of wedlock, as one example). Some other examples: religious community is more socially cohesive and valuable among poor people than the rich, so dismissing it as unnecessary or backward is a luxury belief. Poor children, who don’t get to play in expensive sports leagues or attend expensive after-school karate lessons, are a lot more likely to need multiple authority figures and caring adults to keep them out of trouble than rich kids who are rarely unsupervised. Marginalizing religious community harms the poor, not the rich. Additional example: a poor woman is more likely to derail her life and the lives of her children through sexual promiscuity than a professional woman whose income is sufficient to provide for any child resulting from said promiscuity. Single parenthood is never ideal, but single parenthood when the child gets a full-time nanny providing one-on-one care and always has access to nutritious food and medical and mental health care is significantly less detrimental than single parenthood when the child experiences unstable, inadequate care from a revolving door of babysitters and mom’s boyfriends.

His willingness to take on the right-wing luxury belief that parents and childhood environments don’t matter. The data on fatherlessness alone should cause the genetic determinists to pause and inquire, “Do kids with genes that predispose them to suicide, early sexual involvement, substance abuse, incarceration, and low academic achievement also just—by sheer coincidence, wow!!—have father-repelling genes, or are we maybe just a tad too secure in our conclusions that parents and environments don’t matter?” But there’s a contingent on the right who clings to this silliness with all the intensity of Wokists insisting that boys and girls are “assigned” and not recognized at birth. Rob is one of the few non-Woke people willing to call bullshit on this stupidity.

All that to say this: I picked up his book quite generously disposed towards the author, for deep-seated reasons, and hopeful of a good reading experience.

My high, hopeful expectations were wildly exceeded.

It is hard to write a positive book review for the same reason it’s hard to build something solid and lasting. A snarky takedown is easier and more fun, just as breaking a window is far easier than installing one.

But this book is so good, it’s 3:18am and I’m making the effort.

A Kinda-Sorta Content Warning

If you had a trauma-blighted childhood, in reading this book you will repeatedly have that unique mixture of pain and relief that makes you shiver a little and shake your head slightly. Because in reading this book, you will repeatedly have the feeling you get when someone who absolutely gets it uses the exact right language for something that you experienced and that the little-kid part of you still sometimes wonders if you were alone in ever experiencing. Just know that, going in.

With that caveat, I regard the book as appropriate for ages twelve and older.

Peripatetic Before He Could Read

Rob was born to a young woman with a drug problem who loved him but was unable to prioritize his needs. Consequently, he was placed into foster care, where he spent the first seven years of his life, being shuffled from placement to placement.

At age seven, he was adopted by the Hendersons, a family headed by a married couple who at first seemed well-meaning, and of course adoption promised stability and permanence.

About a year later, his adoptive parents divorced. His adoptive father then rejected him as a way to punish his adoptive mother. The pain of this rejection was compounded by the fact that his adoptive father did not reject his biological child, Rob’s younger sister. Thus Rob spent the rest of his childhood watching his sister go on visitation with her dad—with the man he had thought was going to be his dad—a kind of ongoing salt-in-the-wound for which the senior Henderson would, if gods existed, spend an extra millenium or three in purgatory or hell or wherever people go to contemplate their poor excuses for wanton cruelty.

After the divorce, his mother did the best she could to provide Rob with love and support, but was limited in what she could do for him. Poverty, economic struggle against the backdrop of 2008’s market crash, and other issues created obstacles. Rob was an uneven student, rarely putting in the effort to live up to his potential, with a poor high school record to show for himself: many physical fights and low grades.

The US Military, Then Yale

Chapter seven was the first place where I grabbed my Apple pencil and started highlighting. In chapter seven, Rob enlists in the US military. I grew up in the kind of neighborhood where just about every boy either ended up in the US military or prison, and he gave me something I’ve needed for years: the language to articulate precisely why this dichotomy exists.

“Even if a young man learns absolutely nothing during a military enlistment, that’s still four to six years he spent simply staying out of trouble and letting his brain develop; the same guy at twenty-four is rarely as reckless and impulsive as he was at eighteen. The reason my life didn’t go off the rails is because I was just self-aware enough to decide to have my choices stripped from me.”

Among the many game-changing insights he gained in the US military was this one:

“But the military taught me that people don’t need motivation; they need self-discipline. Motivation is just a feeling. Self-discipline is: ‘I’m going to do this regardless of how I feel.’ Seldom do people relish doing something hard.”

This is a crucial lesson, and one that kids who grow up in chaos and poverty often miss because of their circumstances. In order to teach delayed gratification to their kids, parents first need the ability to meet the child’s needs and thus to have gratifying a child’s desires—either immediately or in the future—be an option under consideration at all. Without the stability to make meeting the child’s needs a consistent experience, delayed gratification is something the parents cannot teach their kids, any more than they can teach their kids to speak Mandarin.

After his enlistment, an experience that was mostly positive but that also included some very difficult times (including developing an alcohol problem for which he required treatment), Rob earned admission to Yale.

Luxury Beliefs in Theory

Yale was where Rob first began developing his thesis of “luxury beliefs,” which I explained briefly in the section about my own priors. From the book:

“In the past, people displayed their membership in the upper class with material accoutrements. But today, luxury goods are more accessible than before. This is a problem for the affluent, who still want to broadcast their high social position. But they have come up with a clever solution. The affluent have decoupled social status from goods and reattached it to beliefs.”

“Advocating for sexual promiscuity, drug experimentation, or abolishing the police are good ways of advertising your membership of the elite because, thanks to your wealth and social connections, they will cost you less than me.”

He was at Yale during the fall 2015 debacle involving Nicholas and Erika Christakis, when the mere suggestion that Yale students were capable of choosing their own Halloween costumes was regarded as violent and harmful. This provided fodder for reflection on the many contradictions.

From page 246: “A student from Greenwich, Connecticut, who had attended Phillips Exeter Academy (an expensive private boarding school), explained that I was too privileged to understand the pain these professors had caused. At first, I was stunned. But later, I came to understand the intellectual acrobatics necessary to say something like this. The student who called me ‘privileged’ likely meant that due to my background as a biracial Asian Latino heterosexual cisgender (that is, I ‘present’ as the sex I was ‘assigned’ at birth) male, this means that I have led a privileged life. However, I also learned that many inhabitants of elite universities assign a great deal of importance to ‘lived experience.’ This means that your unique personal hardships serve as important credentials to expound on social ills and suggest remedies.

“These two ideas appeared to be contradictory.

“Which is more relevant to identity, one’s discernible characteristics (gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and so on) or what they actually went through in their lives? I asked two students this question. One replied that this question was dangerous to ask. The other said that one’s discernible characteristics determine what experiences they have in their lives. This means that if you belong to a ‘privileged’ group, then you must have had a privileged life. I dropped the conversation there.”

Rob’s Substack and Twitter are well worth following for more on luxury beliefs and how they’re a crucial component in the ongoing decimating of everything that matters.

Class Climbing

At Yale, he was suddenly surrounded by the children of the most privileged, by people whose childhoods had been so radically different from his that their baseline assumptions were often inverses from his own.

This was one of my favorite passages: “Later, I read a study from another Ivy League school—Cornell—which reported that only 10 percent of their students were raised by divorced parents. This is a sharp juxtaposition with a national divorce rate of about 40 percent, which itself is quite low compared ot the families I’d known in Red Bluff. When I explained to a classmate how disoriented I felt when I discovered these differences, she replied that this was how she felt when she learned that seven out of ten adults in the US don’t have a bachelor’s degree, because that was so out of line with her own experiences.

What? I was surprised that it was only seven out of ten, because so few people I’d known were college graduates.”

Class climbing is an experience I’ve written about here on Substack. Rob’s discussion of learning the expectations and norms was familiar and made me grin many times, especially the section where he freaked out a girlfriend’s family by cutting food with his fork. I was somewhere north of sixteen years old the first time I knew why sometimes there is more than one fork on a table, so I knew exactly what that experience was like.

Like most class climbers, I could write a book of my own about this. (I learned yesterday that I’m the only person in my entire department who does my own taxes. It just…never occurred to me to pay someone else to do them.) This aspect of the book will be especially enjoyable to any readers who are also class climbers.

Emotional Wreckage from a Dark Past

The process of emotional recovery from his childhood is one of the best-handled sections of the book. He recognizes that this is different for everyone and goes into enough detail to make clear the wreckage of his childhood did not leave him unscathed, but never makes assumptions for how others can, will, do, or should feel. And the details never become salacious or feel exploitative.

From page 291: “The most frightening thing was admitting that I felt unlovable and undeserving of love. I’d been betrayed so much as a kid. When adults make children feel like they’re incapable of being loved, kids retain those feelings, and they often don’t go away. And when children feel unworthy of love, they want to hurt people and do bad things.”

Everyone’s experience of recovery from a dark past is different. The efficacy of the foster care system at protecting kids is something I’ve discussed many times with a friend of mine who, like me, experienced child abuse at home without being taken into foster care. Would we have been better off? We think it’s at least possible—worst case scenario, being abused by strangers may be less damaging than being abused by people whose love evolution programmed you to desperately need. But these conversations also always include an acknowledgement that instability and attachment difficulties would’ve been one cost and that ultimately there’s no way to be sure. One way that Rob’s book helped me personally was to provide specific insight into some of what would have been on deck for me and others like me if we’d been put into the system.

Interestingly, he developed the same conclusions from his experiences that I and others who grew up with parental abuse at home but stayed out of foster care concluded:

“….had furnished a few lessons about relationships: never get too attached to anyone, be prepared to walk away at a moment’s notice, and everyone is replaceable.”

Later, reflecting on his time in rehab and the therapist he met with there, he writes: “After our first session, I realized that whenever anyone said they loved me, I heard the words but never internalized them. It was the same as someone saying ‘good morning’ to me. Just a nicety.”

This was the part that made me shiver, start crying, and realize I was going to have to put a content warning on this book for other PTSD types who might read it. Childhoods define “normal” for us, and thus they really matter. One way they matter is this one—and it’s something that the people who cling to the luxury belief that childhoods don’t matter will likely never be able to comprehend their cruelty in denying.

For Rob, “I love you” is a nicety, like “good morning.” For friends of mine, “I love you” is an impending threat—something that people say when they’re going to hurt you. For me, “I love you” isn’t quite a nicety. It’s more of an anxiety soother, something akin to checking the doorknob again when my OCD is flaring up. It doesn’t mean that someone actually loves me. It means that they’re unlikely to do anything terrible to me in the immediate future. (After years of therapy and a metric fuckton of work, this is somewhat better, some of the time.)

People who believe that children turn out how they turn out regardless of parenting and environments are telling you that they believe the ability to regard oneself as lovable is inconsequential. They’re either stupid or lying—to signal their status as luxury belief holders.

Luxury Beliefs in Practice

From page 262: “Later, I would connect my observations to stories I read about tech tycoons, another affluent group, who encourage people to use addictive devices, while simultaneously enforcing rigid rules at home about technology use. For example, Steve Jobs prohibited his children from using iPads. Parents in Silicon Valley reportedly tell their nannies to closely monitor how much their children use their smartphones. Chip and Joanna Gaines are well-known home improvement TV personalities who have their own television network. They don’t allow their children to watch TV and don’t own a television.”

I grinned throughout this passage; it was so familiar to me to see evidence of people spouting beliefs they clearly don’t believe. I used to have an active Twitter presence and would sometimes argue there about the right-wing luxury belief I mentioned as one of my Rob-knows-his-stuff priors at the start of this review and have referred to repeatedly: whether childhoods and parenting matters in how kids turn out. Similarly to the hypocrisy in Rob’s recounted conversations with Yale classmates, my interlocutors on Twitter would often have these arguments with me after their children were asleep. Their children, who had been carefully tucked in with a rarely-varying routine that included monitored tooth-brushing, bedtime stories being read to them, and a night light being turned on before the hug, kiss, and “I love you.” Their children, who have strict screen time limits, are read to daily, and only eat candy on rare and special occasions. They would make these arguments to me quietly lest they disturb their sleeping children, whose lives reflect in every conceivable way the parental belief that parenting matters one hell of a lot—the same parent signaling their status by blathering this luxury belief that parenting doesn’t matter.

Another memorable passage was a conversation Rob had with a fellow veteran who was also a student at Yale, one that throws into sharp relief how dangerous luxury beliefs are to the functioning of a free society.

“Something’s off about the whole thing. We swear that oath about upholding the Constitution. Then these rich kids who are the same age as us when we enlisted are actively undermining it. Pretty weird.”

“Undermining how?” I asked.

“The first two amendments,” he continued. “The general opinion at these schools is that the first needs a major overhaul and the second should be completely dismantled. Seems like we basically got duped into believing we are upholding American values while the future ruling class are figuring out ways to undermine them.”

Indeed.

Agency Is A Life-Defining Skill

From page 282: “Successful people tell the world they got lucky but then tell their loved ones about the importance of hard work and sacrifice. Critics of successful people tell the world those successful people got lucky and then tell their loved ones about the importance of hard work and sacrifice.”

Having to learn the art of agency as an adult is one consequence of a childhood that’s unstable, chaotic, or abusive. If your best efforts to be good and please the adults result in a failure to achieve love—failure to be kept around, as in the case of a foster child like Rob—or if those efforts still result in a physical, verbal, or emotional beating, then children learn that they aren’t agents. They learn that their actions have no influence on subsequent events. The concept of cause-and-effect becomes something that is not remotely intuitive and thus mistakes, even mistakes that from the outside seem obvious and thus easily avoidable, are infinitely more likely to result—even from best efforts.

On page 232, he writes: “People have choices; we’re not billiard balls traveling along preordained trajectories with no say in the matter.”

Everyone I’ve ever met, listened to, read, seen, or observed who claims to believe otherwise nevertheless puts in enormous effort to teach their own children how to make careful, conscious choices.

The US military, voracious reading, and his own capacity for self-reflection taught Rob agency. This is a crucial lesson for any adult who didn’t learn it as a kid to make up, and the world is much improved for the blessing that Rob was able to find it, utilize it, and articulate the lessons learned as an adult.

The Best Side Effect of A Book

When a book gives me a light bulb moment and makes something about the world around me make more sense, I regard that as evidence that the book is truly great—something more than an enjoyable way to spend five or six hours. Rob’s book did that.

I haven’t been able to stop thinking about one aspect of this book: the extent to which dishonesty is entirely normalized in our society among the elite. The luxury classes people pretend to believe that marriage doesn’t matter, but very few of them have children out of wedlock. They pretend to believe that fat-shaming is a serious moral affront, while they spend a fortune on organic food and personal trainers to keep themselves fit and trim. They pretend to believe many things that their lives betray they don’t actually believe at all.

It’s easy to think that most of them are just going along with the crowd and don’t realize they’re lying, but the truth is that most of them do know, which is why they expressed agreement with Rob in private. This is a familiar dynamic; I used to get DMs on Twitter from people apologizing that they couldn’t follow me (though they made a point to daily read my tweets) without upsetting their coworkers. These people included a couple of college professors, a Unitarian minister, and a couple of therapists, and possibly others I’ve forgotten.

Dishonesty is so normalized that this kind of performative fragmentation—signaling that one believes certain things while acting as if one believes other things—may eventually be recognized as a marker of intelligence and proper preparation for class climbing (or class maintenance, if one starts off in that class).

This dynamic is going to destroy us all if we don’t find a way to fix it. Soon.

Conclusion

From page 290: “Whatever sympathy you felt while reading my story, please channel it towards kids currently living in similarly unpromising environments. And then think carefully about the luxury beliefs, practices, and policies that gave rise to their predicaments.”

The book is well worth your time and energy to read it, but you know what? Even if you’re not a book reader, if you can afford it you should buy a copy anyway. Buy it and donate it to your local library, your local high school, or give it as a gift to any young person in need of inspiration.

Alternative idea: read it and get any teenager in your life to read it. As soon as the children in my life are old enough, I pay them $20-$100 (depending on length and complexity) to read and then discuss books of my choosing with me for an hour. If you choose the kid, the book, and the timing carefully, this is a potential game-changer. Rob’s book is on my list for future interactions of this nature.

Rob has been unable to line up bookstore events because his non-Woke take on the world—a failure to espouse the luxury beliefs that signal moral virtue to the crowd who gatekeep bookstore events—has him marked as a traitor to the luxury class. His story of overcoming adversity doesn’t count for the same reason that Thomas Sowell doesn’t count as a black guy to that crowd.

Buy a copy to support someone whose courage has earned your support, and to send a middle finger to the Woke idiots who look at him and don’t see a real POC with a marginalized voice that needs boosting.

It’s a fantastic book. Seriously.

Amazon link to buy. Audible link for the audiobook. Barnes and Noble link to buy.

About My Substack: I’m a data scientist who would rather be a math teacher but, being unwilling to brainwash kids into Woke nonsense, am presently unqualified to teach in the US. So I bring my “math is fun and anyone can learn it” approach to mathematics here to Substack in my series, “How to Not Suck at Math,” (first five entries not paywalled, links at the top of part 5, here).

I also write about other things. My posts are mostly cultural takes from a broadly anti-Woke perspective—yes, I’m one of those annoying classical liberals who would’ve been considered on the left until ten seconds ago. Lately I’ve regained a childhood love of reading and started publishing book reviews. My most widely useful essay may be this one, about how to resist the demon of self-termination.

I used to be poor, so this Substack has a standing policy: if you want a paid subscription but cannot afford one, email me at hollymathnerd at gmail dot com and I’ll give you a freebie.

WRT ultra-successful people, I expect a great many attribute their success to "luck" in a misplaced attempt to avoid appearing prideful.

I confess I am surprised to learn there is much in the way of luxury belief among conservatives who aver to parenting not being important. My inner circle is admittedly parochial, and is comprised mainly of military veterans, cops, hunters, observant (as opposed to religious) Christians. My outer circle (family friends) are mostly "hands-on" academic types who worked in LSU's cooperative extension service. Of all of them, I don't know any who say one thing publicly and another privately.

Some people succeed in life in spite of their upbringing. You, Holly, and my dad, are 2 good examples of that. But having been a cop in Houston, I suspect people like you are quite the minority. Without the civilizing influence of 2 parents, I suspect most kids end up being like "the big'uns" from Lord of the Flies. We all seem to be a muddy mixture of upbringing and our own internal compasses.

Rob Henderson points out that chaos and instability in a child’s life is far more damaging than poverty. This is another truth that triggers the progressives. This is true without regard to race, sex, or any other factor. The rates at which people who are alumni of the foster care system, of all races, who graduate college is far lower than those of children of all races who grew up in poverty, for example (although the degree of chaos in their families is predictive as well). And foster children have rates of deaths of despair from suicide or overdose throughout their lives that exceeds other demographics by far.

This phenomenon demonstrates the lie behind progressive’s sneering contempt for white people as being expressed with the use of the term “white privilege”, about which Holly has written. A child’s family life is a massive predictor of their future, and personal agency and good luck are their only hope for escaping statistical destiny.

There are some very dedicated people trying to fix the foster care system, but for the most part it is not on the radar of either the public or the political class. We absolutely have to fix this system, because it is an abomination against humanity, and is right under our noses.