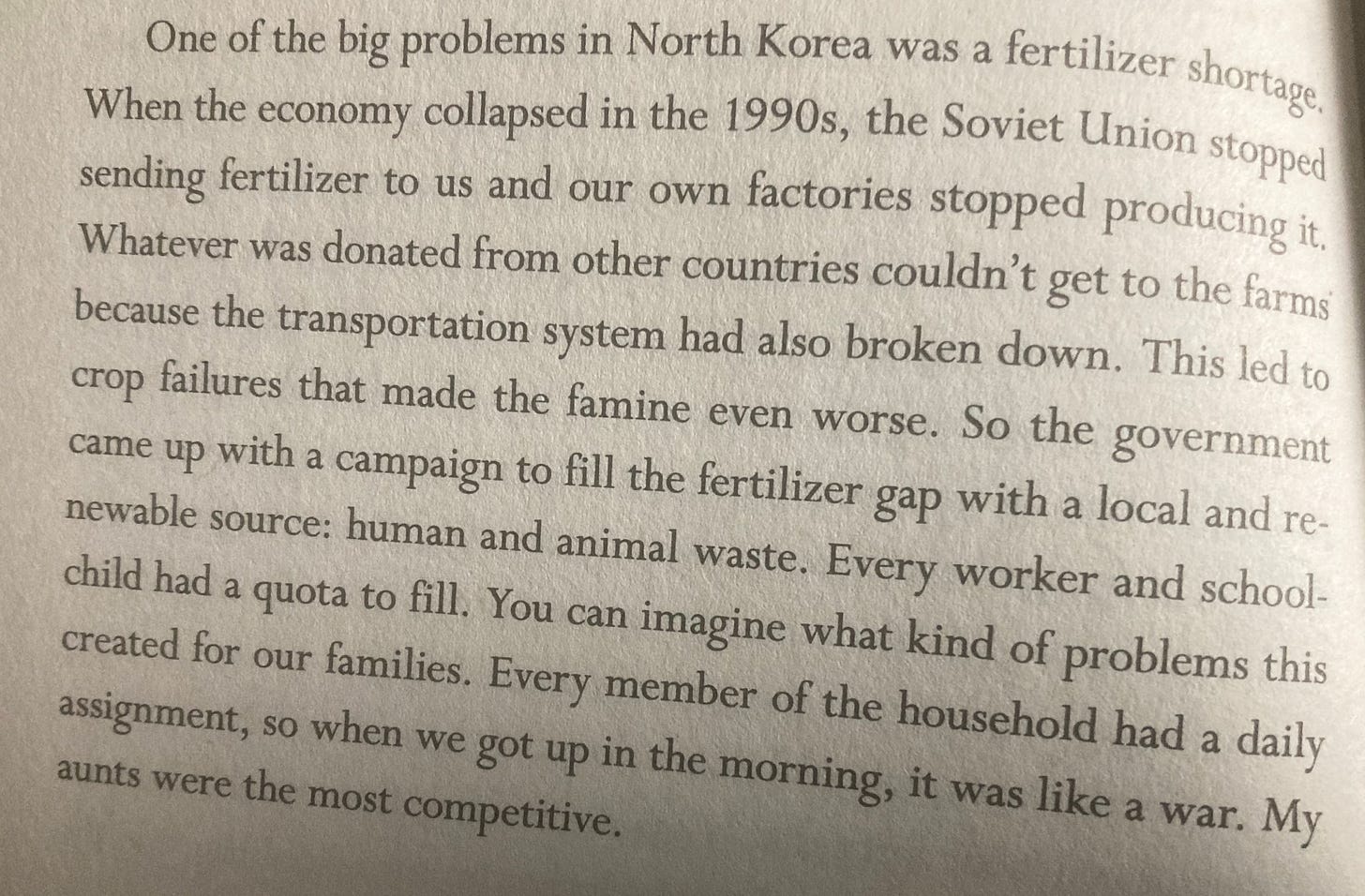

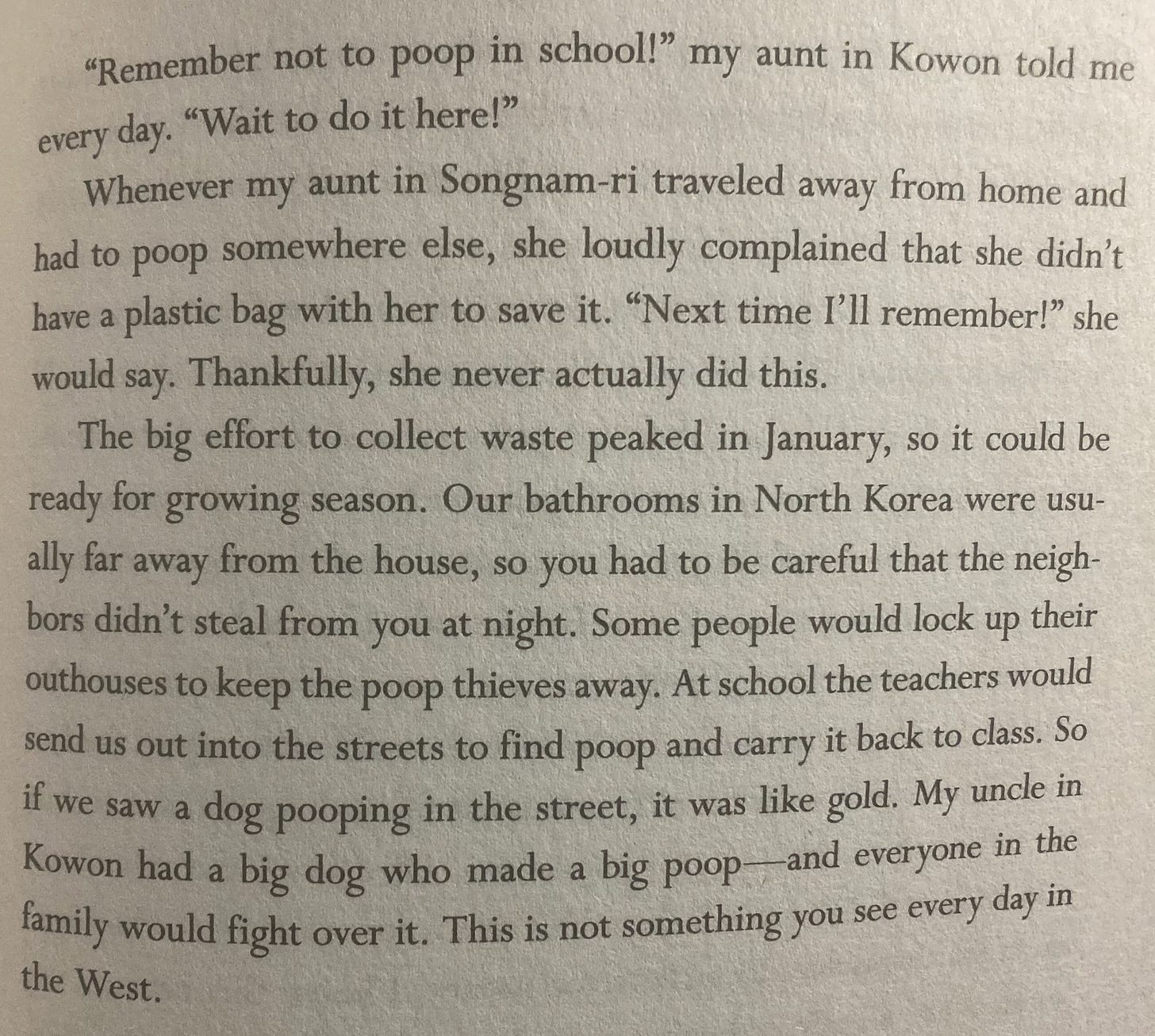

North Koreans are required to save and submit their shit.

This is not a metaphor.

The ongoing holocaust, primarily by starvation, of twenty-six million North Koreans at the hands of their government is so severe that the dictatorship requires citizens to save their shit for use as fertilizer.

Even the waste products produced by the digestive processes of North Koreans belong to the state. Absolutely nothing belongs to the individual. North Koreans are brainwashed and mentally enslaved to the point that they compete with one another to see who can produce the most feces for the glory of their leader, Kim Jong-Un.

I learned about this remarkable fact of life for human beings in North Korea—happening right now, today, in the era of self-driving cars, on the same planet where most of you are reading this on pocket-sized computers that are more powerful than the ones humans used to leave footprints on the moon—by reading In Order to Live, the remarkable memoir by Yeonmi Park.

The book tells the story of her childhood in North Korea and how she and her family took the astonishing risk of defecting from the most brutal totalitarian regime on earth today. I ordered it while reading her second book, While Time Remains, a powerful call to action that should be read by every American parent and teenager. Her second book points out the many eerie parallels that Park experienced, in her time at Columbia University, between the propaganda of her childhood and her Ivy League education in the United States. (I reviewed it here.)

Park’s book is unironically stunning and brave, and it deserves a sole-focus review, but I’m moved to write about it now, as the sun comes up, for what it’s provoking in me: a deeper appreciation for the gift of suffering.

Suffering, and how we choose to react to it, are at the root of what is deepest in our humanity: our powers to choose, to assign meaning, to experience sacrificial love, and to thrive despite adversity.

Ancient Wisdom on the Source of Meaning

These ideas are, of course, ancient.

As far back as the Buddha and the Stoics, humans were discussing these truths: that life is suffering, that outward focus is the source of happiness, that we are defined much more by how we choose to react than by what happens to us.

In 2023, in the West, we seem to have forgotten this wisdom.

If we don’t remember—soon—we will lose everything that matters.

Political tribes often use the suffering of themselves or their group as leverage, or even just material with which to make a point. Moral foundations theory can help us understand the way different political philosophies and worldviews weigh suffering.

Much of political discourse amounts to arguments over who cares the most about suffering. The focus on suffering can make arguments seem absurd when we don’t agree on terms. Critical theorists assert that never-ending suffering is endured by ‘the marginalized’ in the face of crimes such as ‘digital blackface,’ a white person using a gif or meme that contains a black person to represent their reaction, or the necessity of walking by a statue of a person who was progressive for their time but not ours. Conservatives can fail to respect real suffering, especially the kind caused by structural barriers that actually exist, particularly situations when the hardest work someone is capable of performing just isn’t enough to help them escape poverty.

These arguments intersect with differing principles of personal responsibility. Those on the farthest left want the abolition of police and prisons, even if cold-blooded murderers are then set free, while simultaneously cheering the ‘accountability’ of an 18 year old losing her college admission over a slur used years previously.

And much of the right is seemingly fine with situations that create structural barriers to success. We are currently having a cultural conversation about student loans, the riskiest kind of debt—the kind that can never go away through bankruptcy—offered to people with the least experience in managing debt, with colleges subsidized by the government to over-promise and under-deliver, and consequences affecting only the student when the rigged system doesn’t work.

There is a much larger and more important aspect of suffering than who suffers, who can eliminate it, and who is it fault; and it’s one that our culture ignores, to our detriment.

Every Human Life Is Unfair

“You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” —Marcus Aurelius

The ancient philosophy of stoicism accepts as a foundational premise that every life will involve suffering; every person’s life path will involve unfair, often brutally unfair difficulty; and the one and only thing we can control—and from which we can derive meaning and personal satisfaction—is our reaction. It is the one and only thing that is always ours and can never be taken away.

Stoicism promotes resilience and the power to choose one’s reactions, but it goes deeper than that.

In recognizing the need to face life with the four cardinal Stoic virtues of wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice, the philosophy recognizes that we need these tools because we need the difficulty of suffering to find the best in ourselves, and thus, to really be happy.

We seem to have forgotten that the state of having nothing to struggle for — no pain, hardship, or distress to ameliorate through your own efforts — is itself a type of suffering.

We need to be able to strive, overcome difficulty, and achieve through our own efforts. It defines us, provides meaning, and helps us to both know who we are and choose who we will become.

This is why we are now inventing problems, ludicrous and farcical nonsense like high ATM fees, political enemies who insist that 2 + 2 always equals 4, or being ‘misgendered’.

This is hardly an original thought, of course, but it matters, and the evidence is everywhere. The dichotomy between the value we place on things we struggle for, things we achieve despite actual difficulty, vs things that are easy is universal, and can be seen in myriad circumstances. In college, I cried with joy to earn low B’s in most of my mathematics courses, because mathematics is rigorous, difficult, and required endless effort. In my humanities courses, turning in a rough draft and getting an A was common. Writing (of the sort needed for college courses, not writing in general) is easy for me.

Mental Freedom Is the Most Precious

Freedom came at a terrible cost for the Park family. Her father died of untreated cancer before seeing his family free. The women’s journey to freedom, among other desperate measures, included a wintertime trek across the Gobi desert with razor blades and poison on their persons in order to commit suicide if they were caught. Suicide was the backup plan; it was how they would save the other members of their group (and themselves from being returned to North Korea to be tortured to death).

Park and her mother were both raped and sex trafficked by Chinese people who earn money by buying and selling North Korean women.

Park was thirteen when a rapist took her virginity.

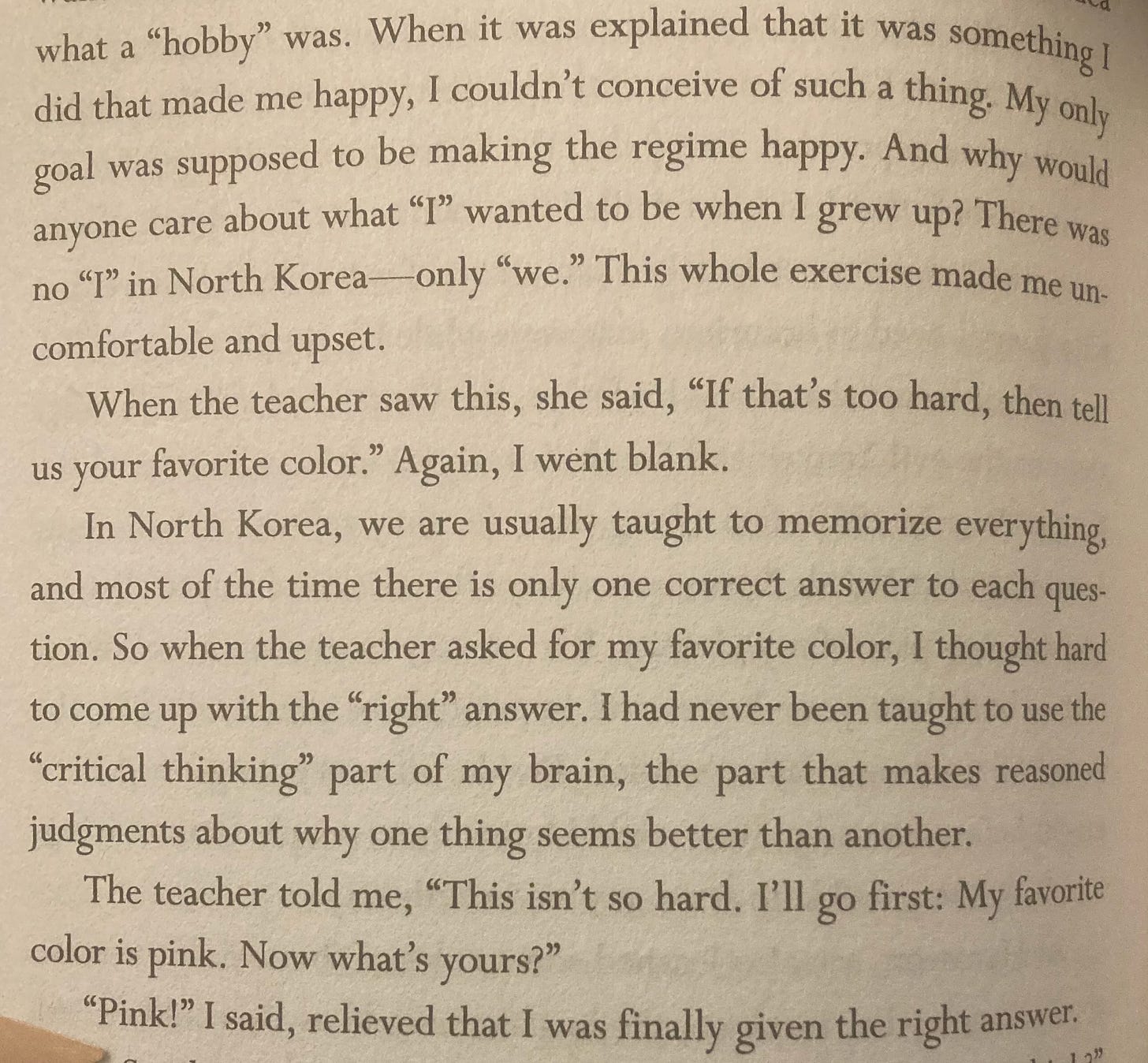

What has struck me the most throughout her remarkable books—what is in fact haunting me, the reason why I’ve been awake all night, first finishing her book and then thinking about it—is how excruciatingly difficult it was for her to overcome the doublethink demanded of each citizen, including children, by the North Korean dictatorship.

North Koreans simply have no words for depression, trauma, stress, or even love—aside from love for the dictator. The concepts do not exist in any way that can be expressed with language. These ideas are not permitted to exist.

They live with the constant threats of starvation, brutal punishment or execution at the hands of the government, and the required practice of struggle sessions. Each week, North Koreans gather with their neighbors to publicly criticize themselves for their thought crimes, typically failure to love and praise the Dear Leader with sufficient devotion, and submit to this treatment from others.

At the same time, they believe so thoroughly and utterly that they live in a socialist paradise, the luckiest people on earth, that when Park and her mother escaped to the West they frequently felt sure they were hallucinating over how much better everything was—the abundance of food, the quality of medical care, the freedom to make choices.

I recognize the traumatic sort of doublethink that Park describes from my own experience with complex-PTSD, which can cause psychological fragmentation sufficient to make a person truly believe contradictory things at the same time.

The doublethink born of brainwashing and trauma is a recurring theme throughout the book, but I also see a related aspect of it in the world around us.

Mental Freedom Can Be Painful

I got through college, to my regret and shame, not speaking up anywhere near enough when presented with professors insisting that obvious bullshit was true. It was simply easier to pretend that I believed flagrant nonsense, such as white kids in foster care in West Virginia being more privileged than Sasha and Malia Obama, that “non-binary” identities are anything but an expression of narcissism, or that womanhood is defined solely by a feeling in the mind of an individual, even an individual with xy chromosomes who has sired children.

This performative doublethink is apparent in our leaders, who simultaneously declare America to be a hellpit of horrific racist oppression, and then immediately cite, as evidence of America’s terrible inhumanity and lack of compassion, political desire to close the border and let fewer people into our country—thus, by their own logic, limiting the number of new people who would be forced to suffer horrific racist oppression.

It is easy to turn one’s will and thinking over to a higher authority, to an approved set of principles and beliefs that confirm one’s virtue and goodness for performatively demonstrating belief in them.

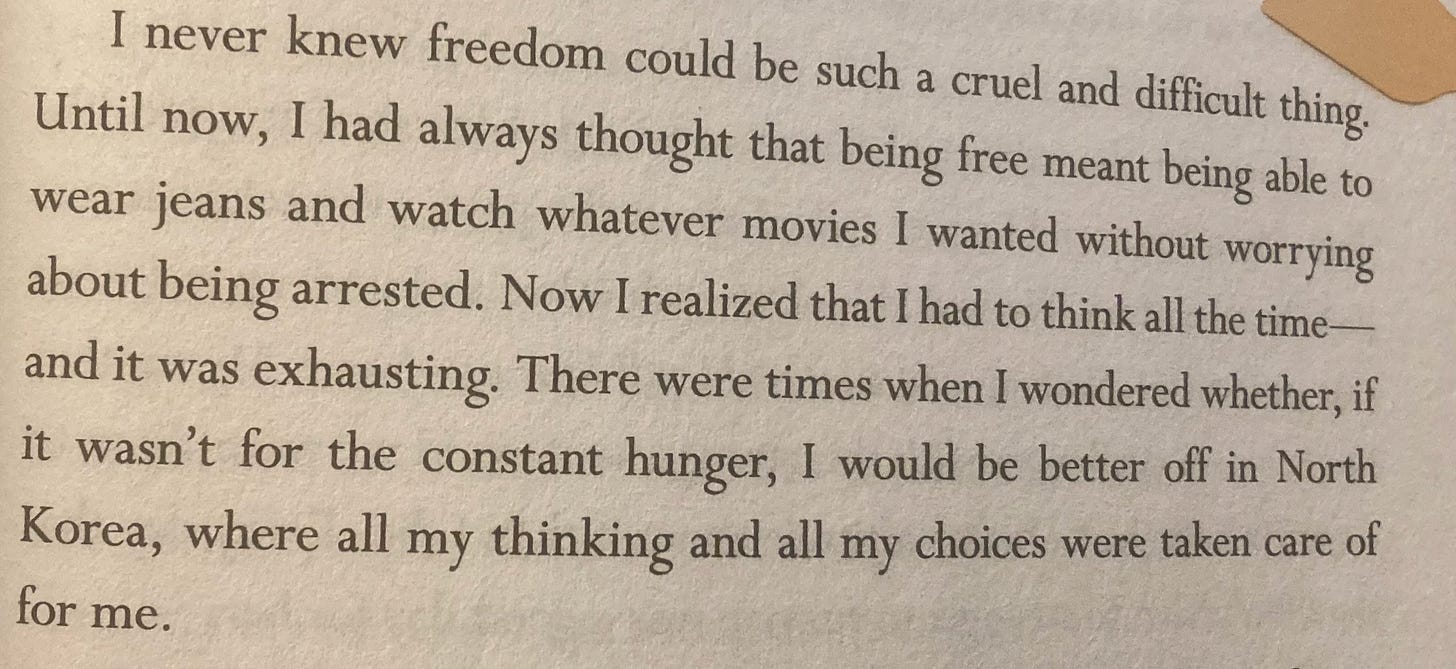

Park’s courage in admitting to the difficulty of learning to own her own mind and think for herself was especially moving to me.

Redemption and Self-Acceptance

The most challenging part of finding meaning in suffering, for many of us (yes, including me), is granting oneself the possibility of redemption and striving for self-acceptance.

Park weaves this aspect of finding meaning and grace into her story effortlessly, making me cry more than once at the humility demonstrated by forgiving herself for what she had to do to survive.

In order to survive being trafficked by violent rapists and protect her mother, at times she had to help her abusers to traffic other women. She also refers to “doing what (she) had to do” when, in the absence of birth control, her life of repeated rape would result in the sudden onset of morning sickness.

Later, still a young teen, she did online pornography on camera and in chat rooms, taking requests from men paying by the minute.

The self-forgiveness and self-acceptance Park has found are enviable, and rooted in the humility of seeing herself clearly: as a flawed and fragile human who did the best she could in tragically terrible circumstances.

No more. And no less.

The contrast with modern Western Woke culture, where redemption is almost a non-existent concept—indeed, whether or not one is guilty of the sin of racism is answered forever by one’s DNA—is stark, and startling. I am loudly anti-Woke, but I confess to exactly the same kind of egotism that Wokesters demonstrate. They hold redemption to be impossible for the outgroup; I have for too long denied it to myself. My therapist is always calling me on this penchant for holding past choices against myself in ways that I would never do of anyone else who faced my past challenges. It is precisely the same sin, only manifesting differently.

Park’s example is powerful, and humbling. She demonstrates the truth that crucial to our very humanity is the power to choose the meaning of our suffering—a power we can surrender, but that can never be taken away.

Some Things Really Can Be Not Political

In North Korea, everything is political, up to and including the private act of defecation.

In the West, many are determined to replicate this stifling paradigm and make everything political. It’s voluntary (for now) but I had to spend 24 hours offline this week to avoid seeing pictures and video of a creepy gay man being paid to talk about tampons, so we are probably a lot closer than we think.

This dynamic has its roots in second-wave feminism’s motto, “The personal is political,” but the tiny seed of truth in that aphorism has sprouted, grown, and spread into a crop of insanity.

If we allow it to continue, every aspect of life will eventually be swallowed by political orthodoxy—maybe yours, maybe mine, maybe someone else’s. That is unacceptable on every level.

We must resist it.

We must.

The Value of Suffering for Freedom

I love a quote that’s attributed to FDR: “In the truest sense, freedom cannot be bestowed; it must be achieved.”

Our ancestors achieved a level of freedom previously unknown in human history, and from that has flown prosperity to an almost ludicrous degree.

They wrote founding documents that, while flawed, laid the foundation for passing that freedom and prosperity on to us as a birthright.

In the present moment, we appear to be shoving it away with both hands, and largely because we have such a distorted relationship with suffering.

In North Korea, people worry about collecting enough shit to avoid being sent to a modern-day Auschwitz.

In America, we have so few real problems that when we have an epidemic of unhappy adolescents, we do not teach them to assume responsibility for their own happiness and equip them with a sense of agency.

Instead, we debate at what age they should be allowed to amputate their healthy breasts, hoping this will make them feel better.

Insanity is a mild term for the West right now.

We must re-locate the wisdom of the ancients.

Our insistence on perfect comfort, constant external validation, and total unanimity with every view we hold about ourselves and our precious “identities” is causing us to trade a priceless birthright for much less than a bowl of stew.

This is a mistake that we do not have to make.

We can stop. Now.

Housekeeping: comments are open for paid subscribers, as on most posts. In honor of Elon Musk bringing Substack Notes (on which I am active) to my attention, paid subscriptions are 10% off at this link: https://hollymathnerd.substack.com/elon_self_own.

About My Substack: I’m a junior data scientist (two years experience and presently job-hunting if you’re hiring). My great love is mathematics, but I also enjoy writing. My posts are mostly cultural takes from a broadly anti-Woke perspective—yes, I’m one of those annoying classical liberals who would’ve been considered on the left until ten seconds ago. Lately I’ve regained a childhood love of reading and started publishing book reviews. My paid subscribers get my creative writing series, which are generally personal stories but also include excerpts from a novel-in-progress. I have a special interest in the dangers of the modern college campus, helping parents who want to homeschool but are scared they can’t handle the math, and the transgender insanity currently sweeping the West. My most important essays are this one, about the imperative to resist the normalization of pedophilia; this one, advising parents on how to protect their kids from pedophiles; and this one, about how to resist the demon of self-termination. I used to be poor, so this Substack has a standing policy: if you want a paid subscription but cannot afford one, email me at hollymathnerd at gmail dot com and I’ll give you a freebie.

THIS.

The Value of Suffering for Freedom

I love a quote that’s attributed to FDR: “In the truest sense, freedom cannot be bestowed; it must be achieved.”Our ancestors achieved a level of freedom previously unknown in human history, and from that has flown prosperity to an almost ludicrous degree.They wrote founding documents that, while flawed, laid the foundation for passing that freedom and prosperity on to us as a birthright.In the present moment, we appear to be shoving it away with both hands, and largely because we have such a distorted relationship with suffering.In North Korea, people worry about collecting enough shit to avoid being sent to a modern-day Auschwitz.

In America, we have so few real problems that when we have an epidemic of unhappy adolescents, we do not teach them to assume responsibility for their own happiness and equip them with a sense of agency.Instead, we debate at what age they should be allowed to amputate their healthy breasts, hoping this will make them feel better.Insanity is a mild term for the West right now.We must re-locate the wisdom of the ancients.Our insistence on perfect comfort, constant external validation, and total unanimity with every view we hold about ourselves and our precious “identities” is causing us to trade a priceless birthright for much less than a bowl of stew.This is a mistake that we do not have to make.We can stop. Now.

When virtue becomes a self-sacrifice, do not expect men to be virtuous.

It is only within the confines of a truly civilized society where virtue is not a self-sacrifice. NK and China are, to be polite, not civilized.