This is an entry in my Vermont 251 Club series. The main post — which lists all 252 places in Vermont — is here. As I visit each one and write about it, the name will become a live link. I sometimes paywall these and sometimes don’t, depending on my mood. Here are a few free ones. But in general, most of the series will be paywalled, so if you think you would enjoy reading more of these, here’s a coupon to help you subscribe a little cheaper.

I rolled into Brandon under a sky that threatened rain but delivered that strange October light — the kind that sharpens edges, deepens color, makes shadows feel like correct punctuation. It was too fucking hot to be seeing foliage, and it felt like I was committing blasphemy by wearing shorts — but it was almost eighty degrees.

As I drove, I couldn’t shake the echo in my head: Let’s Go Brandon — a joke that’s become a meme, a tacit code, and a kind of political thumb-in-the-eye. But what does that phrase mean in a town like this — a place several centuries old, with waterworn mills, broad tree-lined streets, and a downtown of many, many buildings on the National Register?

Brandon started life as Neshobe, chartered in 1761, then renamed in 1784. In its rise, the town tapped its river power, marble, iron, wood — industries that shaped not just bricks and beams, but the rhythm of daily life. One flash of local lore I lingered on: in 1834 a Brandon blacksmith, Thomas Davenport, invented an early electric motor — proof that the town once flirted with invention as much as extraction.

So when I approached Brandon that weekend, “Let’s Go Brandon” felt like more than a meme. It was a tension: between civic identity and outsider mockery, between local rootedness and national meme culture. What are we cheering — or against — when we say it?

And what does it feel like to step into a town where history hums quietly beneath all that noise?

I’d come partly because of the Brandon Artists Guild, drawn by how it echoes the Milton Artists Guild — a local arts hub linked into Vermont’s Open Studio Weekend, when artists fling open their doors and galleries refresh their walls.

That duality — a place that holds centuries of built structure and yet keeps reinventing how it frames creativity — felt like a perfect setting to photograph, wander, and see what the art said about Vermont now.

I parked downtown and wandered for a long time, circling the same few blocks the way you do when a town’s atmosphere has a kind of gravitational pull. Brandon has that old-New-England geometry — brick storefronts with painted cornices, slate roofs, wide sidewalks that make you feel like walking is the intended mode of travel. The buildings are solid in the way small-town architecture used to be: not grand, just dignified, proportioned for both commerce and conversation.

The Brandon Artists Guild sits among them, one of those storefronts whose big windows blur the line between gallery and street. Around it, the village green and main street form a kind of open-air museum of 19th-century façades: red brick, cream trim, iron stairs, and enough flower baskets to reassure you that someone here cares about curb appeal.

Not far from there, set against a retaining wall of red brick, is the Brandon Veterans War Memorial — bronze plaques mounted in careful symmetry, each name cleanly incised. World War II, Korea, Vietnam. The metal has weathered into that deep brown-gold that catches the sun rather than reflecting it, so you read the names by shadow instead of glare.

Honoring those men and women who served their country, the heading says — plain language, free of slogan. I stood there longer than I expected, tracing the repetition of surnames: local families appearing across multiple wars, the way small towns carry continuity inside their loss.

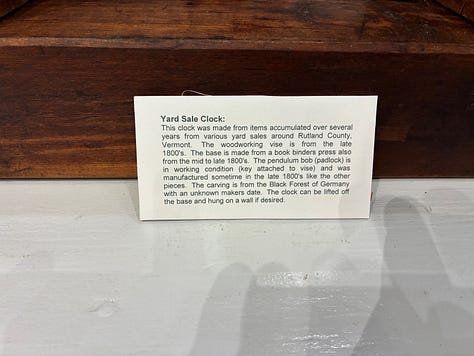

Then I crossed the street and fell into an entirely different kind of museum — the cavernous antique store that anchors one corner of downtown. The place is part archive, part dream logic. I could’ve spent hours in the back rooms: carved ducks with nicked bills, a table crowded with clocks that all disagreed about the time, shelves of toys from the seventies and eighties that hit like a memory you didn’t know you’d lost.

There was the wooden Fisher-Price Jack-and-Jill music box with its red knobs still bright, a yellow plastic phone with a rotary dial the size of a bagel, and a cluster of McDonald’s glasses — Grimace, Hamburglar, Big Mac — still grinning through the decades. A Smurf balanced on top, a little sentry of molded nostalgia.

I photographed the toys the way I sometimes photograph a landscape: not because they’re rare, but because they summon the texture of a vanished world.

Brandon, in that sense, felt like the perfect container for the weekend — a place where reverence and kitsch coexist easily. Bronze plaques and plastic toys, old brick and new art, the serious and the silly sitting side by side, each holding a different kind of memory.

From the antique shop I walked to the Brandon Artists Guild — the place I’d really come for. I’d liked the Milton Artists Guild so much that I wanted to see how Brandon’s compared, especially on Open Studio Weekend, when creative energy feels like it’s in the air itself.

But what hit me almost immediately was absence. Not a lack of skill or imagination — the work was varied and thoughtful — but a lack of something I’d hoped, almost expected, to find.

There wasn’t a single piece in graphite or colored pencil. Not one.

And that really stung, because this isn’t a museum bound by conservation limits or prestige hierarchies. The BAG represents working Vermont artists — people who make things every day, who live here, who see the same light and the same dirt roads I do.

So why did it feel like drawing had quietly disappeared from the category of art?

Do the Vermonters who work in pencil just not think of themselves as artists? If not, why not?

The Milton Artists Guild had at least a few — including one whose colored-pencil realism is so exact it’s indistinguishable from photography, and another whose landscapes shimmer with layered color and atmosphere, the kind that makes you feel the cold in the fog or the gold in a field.

Those pieces lodged in my mind. Because this medium — my medium — doesn’t get much wall space anywhere, and seeing it done with that level of mastery by living, working artists would have felt like being represented. Which, yes, I shouldn’t need, but apparently I do.

Maybe it’s because painting and sculpture still carry the whiff of capital-A Art, the kind that feels serious by default. Oil and bronze can posture as eternal; pencil feels ephemeral.

But drawing something — really drawing it — is a way of knowing it that no other medium can touch.

I’ve been working toward a colored-pencil portrait — my first all-color piece — of a 1968 VW Bug. But I started in graphite to understand it first: every curve, every seam, every plane of light and shadow. The angles of the headlights, the subtle bulge of the fenders, the rhythm of repetition in the wheels — all of it needed to live in my hand before color could mean anything. Somewhere between the door curve and the front bumper, I realized I knew that car now. I understood it. (Which, honestly, makes me sound like I’m about to marry it. I promise. I’m fine. In fact, you can buy the original if you want; I’m not attached. Really.)

Maybe that’s weird. Maybe I’m the only one who draws things as a form of understanding rather than as an end in itself. But walking through the Brandon Artists Guild that day, surrounded by paintings and sculptures and glasswork and jewelry, I couldn’t shake the sense that something essential was missing — not just a medium, but a way of seeing.

Because drawing isn’t just recording what you see. It’s how you learn to see in the first place.

Driving home, I kept thinking about that absence — not just of pencil drawings, but of the kind of seeing that pencil demands. Maybe the real mystery isn’t why graphite and colored pencil get overlooked, but why immediacy gets overvalued.

Painting can dazzle; sculpture can impress. But drawing is humbler, slower. It’s the act of understanding line by line — a form of intimacy that resists spectacle. And maybe that’s precisely why it’s hard to sell.

As the road curved north and the light turned that syrupy late-autumn gold, I started laughing — the phrase back in my head, like a taunt or an inside joke with the universe. Let’s go, Brandon.

But maybe there’s another way to hear it. Maybe it’s not the meme, not the chant, not the borrowed sneer from the internet’s endless shouting match. Maybe it’s something simpler: let’s go as in let’s look closer.

Maybe that’s all I’m doing — trying to look long enough for something to become real.

And maybe that’s what Brandon reminded me: that art, like attention, is a form of reverence.

And reverence — quiet, unglamorous, pencil-gray reverence — still matters.

Original For Sale (Will Not Be Made Into Prints)

Email hollymathnerd at gmail dot com if you’re interested in owning this original drawing. Make me an offer. I’ll sell it to the highest bidder at some point this week.

Pictures from the Brandon Artists Guild