Boys Are Falling Behind While We Look Away

how to get boys into reading so they can start catching up

I’m selling limited-edition prints of my drawings to help pay off my student loans. Items for sale include a pay-what-you-want print of a Texas bluebonnet. Current offerings, shipping times, and how to order are all here.

We are failing boys, and we’re doing it quietly.

In the era of girlboss feminism and "you go girl" empowerment, it’s become gauche—almost taboo—to point out that boys are falling behind. But they are. In school, especially. Boys are more likely to struggle with reading, more likely to be diagnosed with learning disorders, more likely to be disciplined, more likely to drop out.

And the cultural response has largely been: shrug.

Because of my series How to Not Suck at Math, I hear from a lot of homeschooling parents, many of them trying to do right by sons who’ve been underserved by traditional school systems. They often ask for curriculum advice. Occasionally, they mention that their son loves math but hates reading, and ask if I have any suggestions about the latter.

My answer is always the same: most children’s books are complex interpersonal narratives written by women. Which is fine—until it isn’t.

Boys, on average, are less interested in those kinds of stories. The emotional nuance, the subtext, the “let’s all sit in a circle and feel things together” plot structure—it just doesn’t grab them.

So I tell parents to start with nonfiction. Give boys the biggest tiger, the fastest warship, the most dangerous snake. Give them extremes. Give them facts. Let them root themselves in knowledge first, and then gradually coax them toward stories.

But when it’s time to make the leap to fiction, I always recommend the same series—one I loved as a kid. I loved it so much I read it dozens of times, despite being a girl. Which says something.

The old canard about how girls will read books about boys, while boys won’t read books about girls? It mostly holds, in my experience. Maybe it’s because girls tend to develop stronger social skills earlier and can more easily practice theory of mind. Maybe it’s cultural conditioning. Maybe it’s a mystery.

But whatever the reason, I’ve now heard from multiple parents that this series has cracked something open. Their sons wanted to keep reading. They moved on, eventually, to Harry Potter, The Hunger Games, and other such books—but this was the gateway.

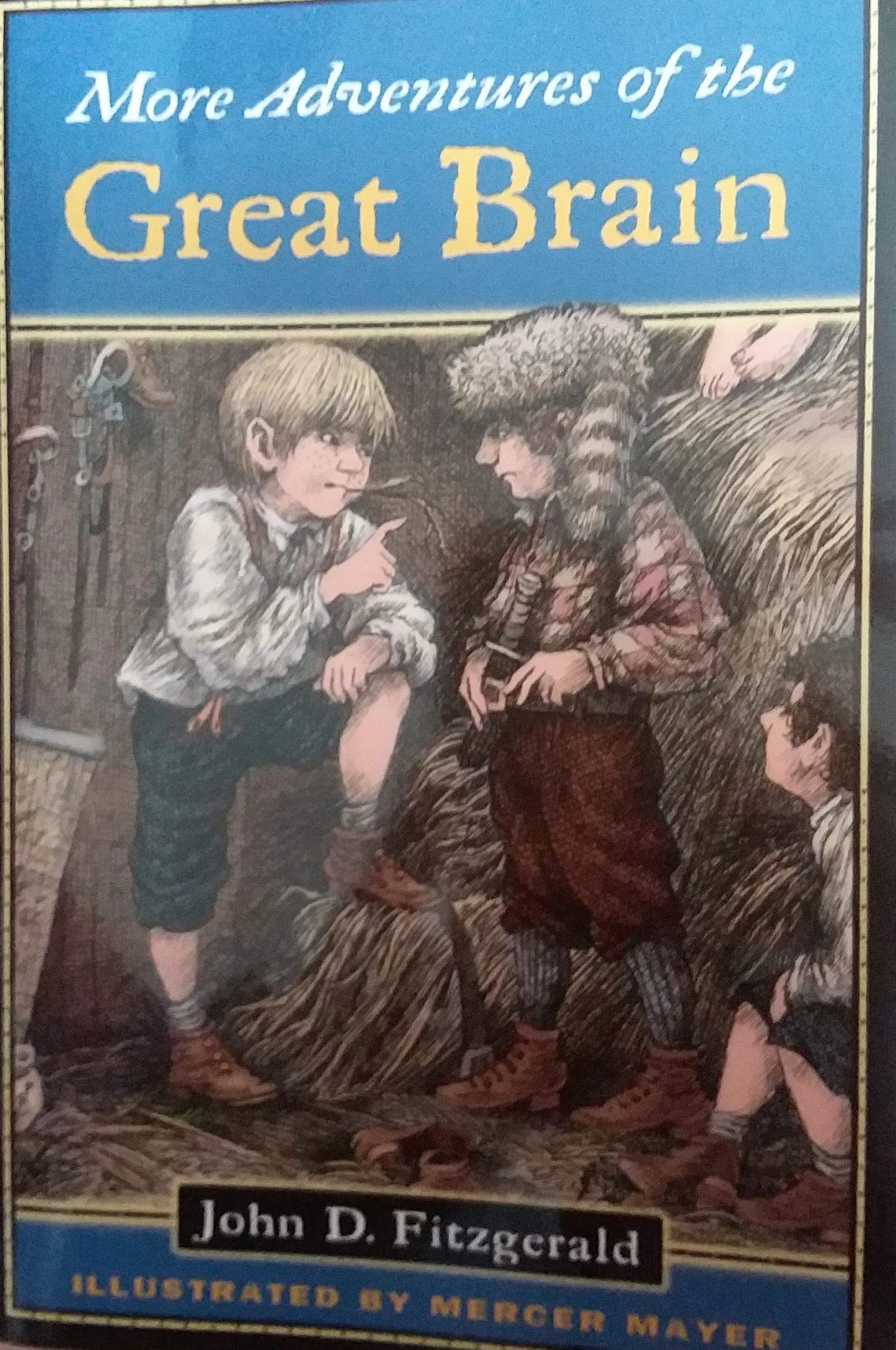

So this is my pitch for The Great Brain series.

The Great Brain books are set in small-town Utah in the 1890s and narrated by J.D., the youngest of three brothers in a Catholic family surrounded by Mormons. The middle brother, Tom—“The Great Brain”—is a con artist in short pants. He’s brilliant, conniving, and entirely unbothered by conventional morality. If he can swindle you, he will. But he’ll usually do it in a way that teaches you a lesson, saves your life, or helps you walk again. Sometimes all three.

It’s part Tom Sawyer, part Encyclopedia Brown, part frontier history—and all deeply satisfying for a kid who wants cleverness and action with just a touch of moral ambiguity. The episodes are tight, funny, and packed with schemes.

It's the kind of story structure that rewards logical thinking and mischievous intelligence—catnip for boys who like puzzles more than feelings.

Tom solves a bank robbery, captures a con man who was in the process of swindling the entire town, runs a whitewater rafting company, dunks the Mormon kids in the canal at the annual Mormons-vs-Gentiles tug-of-war, captures a ghost with a lasso, and wins bet after bet — and that’s just what I can remember off the top of my head.

The writing is clean and accessible, with short chapters and just enough tension to keep a young reader turning pages. There's no overwrought introspection, no pages of someone gazing out a window wondering how they feel about their aunt. The emotional beats are there, but they’re earned through action.

There are seven books written and published during author John D. Fitzgerald’s lifetime, and an eighth—The Great Brain Is Back—published posthumously from his notes. The final book has a slightly different tone, more self-aware and a little more melancholy, but it still delivers the same essential formula: schemes, consequences, and a child’s-eye view of justice.

This series respects kids’ intelligence. It doesn’t pander. And it shows boys a kind of hero they can actually imagine being—not because he’s chosen by a prophecy or armed with a sword, but because he’s quick-witted, observant, and relentlessly strategic.

Bonus: the boy characters are unapologetically proud of being Americans, and in an early book go to great lengths to help an immigrant boy assimilate.

If you want to get a boy to love fiction, you could do a lot worse than starting here.

You’ll probably have to start at your local library, because the series is out of print in paperback and hard to find new. Used copies exist, but they’re getting scarce. The first seven are available on Audible in unabridged format, and they hold up well in audio. The eighth, posthumous book isn’t on audio yet—maybe there are copyright quirks, or maybe it’s just too obscure. Either way, it’s worth tracking down if it ever becomes available.

If you’re trying to reach a boy who’s drifting away from reading—or never quite connected in the first place—The Great Brain might just be the thing that brings him in.

Not with magic wands. Not with chosen ones. But with brains, bravado, and a perfectly executed con.

Because the truth is, we’re not just letting boys fall behind—we’re forgetting to give them stories worth running toward.

I’m selling limited-edition prints of my drawings to help pay off my student loans. Items for sale include a pay-what-you-want print of a Texas bluebonnet and this owl. Current offerings, shipping times, and how to order are all here.

"The Great Brain" came out after I'd gotten into "The Adventures of Tom Swift, Jt." and "The Hardy Boys," so I didn't know it, and offered my sons the books I knew. It is available on Amazon, so I might buy it for my grandsons.

The Second-wave-feminism-inspired changes to education also affected the way school assignments were designed. I very much remember a back-to-school assignment my second son was given regarding one of the assigned summer reading books. It mentioned an action taken by one of the characters and asked, "How do you feel about that?"

"How do you feel about that?" is not a question to ask a young boy. I suggested that he could answer, "I feel hungry about it." A better question for a boy would be "Was he right? Defend your answer." That would get a long response from many boys, but feelings? That's a foreign language. Fortunately, when I contacted the teacher, she told my son to ignore it and gave him a different prompt.

It's not just about complex narratives: boys focus on very different things, and when everything is phrased in girl language, boys will be lost.

Great points, thank you. Note that the series you referenced is available thru Amazon and Barnes and Noble, so there is lots of hope for young readers.

The most baffling mystery of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries will always be why we let so many militant idiots contaminate and ruin our education system. It has become a morass that devalued education in favor of indoctrination, seems incapable of teaching even basic skills, spiraling costs, bloated bureaucracy and militant unions. Teaching techniques, procedures and courses of instruction that worked for generations were jettisoned in favor of ones that are utter failures and serve no one but the unions (and our enemies?).