Better Bent Than Blind

reflections on the limits of loyalty

Loyalty is one of the most admired virtues in human life. We tell stories about it, swear oaths to it, and often measure our worth by how well we honor it.

But loyalty is not simple. It is double-edged. It can bind people together in ways that are noble and sustaining, yet it can also lead us into moral blindness — protecting someone who may not deserve protection, or excusing behavior that ought to be condemned.

So the question presses: how far should loyalty go?

How far would you go to protect someone you loved — even if they did something wrong, perhaps criminally wrong?

Where does loyalty become complicity, and where does it remain a virtue?

A conversation I had with

yesterday forced me back into these questions. We were discussing the text messages between the man who assassinated Charlie Kirk and his boyfriend. Many commentators have dismissed them as crude fabrications, insisting that “22-year-olds don’t text like that.”But to me, that dismissal overlooks something important.

As a non-autistic woman in mathematics, I’ve spent much of my life surrounded by autistic men. Their patterns of thought and communication are familiar to me in ways they may not be to others. Autistic people often build formal scripts in their minds for how to behave in social situations — rehearsed structures of language and demeanor that help them both fit in and reduce the exhausting cognitive labor of daily interaction.

Add to this another influence: the culture of Utah, one of the few places in the West where early maturation and early marriage are still widely supported. In such a culture, fathers and church leaders often emphasize “courtly” treatment of women, preparing young men to adopt an almost old-fashioned style of interaction. When I read those texts — “my love,” “my vehicle,” the melodramatic but earnest insistence on being worried only about his partner — I don’t hear fabrication. I hear the autistic young man who was an academic superstar, raised with courtliness, performing the role of A Good Man Who Loves His Partner, even on the brink of a possible firing squad.

When I lived in Mississippi, I had a Mormon coworker who embodied this cultural training. At twenty-five, with two children and another on the way, he juggled multiple jobs yet seemed devoted to his wife and family. I once teased him that if he was “showing off” for our benefit when his wife visited, it was working. He laughed, then explained how explicitly the Mormon church teaches boys to treat girls and women: don’t waste their time, don’t string them along, be respectful, be serious. His own father had ended both of his pre-marriage relationships within a month, out of respect for the women’s futures.

I told him that the Mormon sales pitch — “families can be forever” — had always been the main reason I could never join. Yet in light of his family and his parents’ family, I could also see its appeal.

We don’t know if Kirk’s assassin was raised Mormon or another flavor of Christian, but geography shapes people. The dominant religious culture leaves fingerprints. Combined with autism’s formal scripts, the formality of those texts doesn’t strike me as strange at all.

So whether those texts were authentic or staged to exonerate the boyfriend, they still carry the mark of reality. They read, to me, like exactly what such a young man would write. And if they still feel, even with these mitigating factors, a bit exaggerated — well, consider the performance layered on top.

He was not only enacting “courtly love” but also clinging desperately to the fiction that his boyfriend was really his girlfriend.

If he had a girlfriend, then he wasn’t really gay.

Josh said he was agnostic, but listened as I explained why I had no trouble believing they were genuine. From there, the conversation veered toward loyalty.

I told him that if he ever did something terrible, I’d be his alibi. I’ve always known Josh was a better person than I am, and he proved it by answering: “If I ever did something like that, don’t protect me. Turn me in.”

I told him I would only turn him in if he hurt a child. Anything else — however terrible or criminal — we’d work out. There would be conditions, maybe hoops to jump through, definitely some long and difficult conversations. But prison? No. Not unless he crossed the line into genuine evil against a child.

Of course, this was bluster — the sort of dark, half-joking-half-serious talk that surfaces when both of us are processing something like the Kirk assassination. We’re both deeply law-abiding. Josh’s anger flares hot but brief, confined to words. Mine simmers longer, steadier, but mostly turns inward.

Neither of us is remotely at risk of slapping anyone, much less killing them.

Still, I fell asleep turning it over. Beyond Josh, there are two other friends I’d protect the same way. The old bumper sticker runs through my head: Friends help you move. Real friends help you move bodies.

But that loyalty isn’t automatic. There are people I love for whom I would never offer an alibi.

Surprising — shocking, even — is the conclusion that follows about my own internal value system.

And it’s this: what makes the difference is not my trust in Josh and the others, but my trust in myself. I trust my own judgment about which friends are truly worth protecting, whose character and history justify that kind of loyalty.

The distinction matters. My willingness to cover for them isn’t blind; it’s rooted in my conviction that I can tell the difference between someone who deserves protection and someone who doesn’t.

Is that pathological? Is my instinct to shield the people I love evidence of dysfunction, of trauma, of something diagnosable?

Well, it’s a day that ends in Y.

And yet the question lingers. Maybe my willingness to shield those I love is exactly what loyalty is supposed to be — love that endures even when it’s tested, love that refuses to hand someone over to a world eager to destroy.

Maybe it’s strength, not sickness.

Maybe it’s the instinct that keeps families and friendships alive across centuries of human struggle: stand by your own, no matter what.

But maybe it’s also the echo of trauma — the child who once protected abusers, now grown into an adult who reflexively offers cover. Maybe my version of loyalty is not loyalty at all but fear: fear of abandonment, fear of disconnection, fear that love can’t survive unless it comes with the promise of secrecy.

So which is it? Fidelity or pathology, devotion or dysfunction?

Probably both, braided together like strands of the same rope.

What I know is this: loyalty, in its rawest form, doesn’t ask for moral purity. It doesn’t even ask for justice. It asks only for presence — for the refusal to leave when the world says you should.

And that’s where my own version draws a line. I’m not loyal to everyone I love. I’m loyal to the ones I’ve judged, with the full weight of my experience, to be worth it.

That’s not blind allegiance. It’s a gamble on my own discernment.

It’s loyalty filtered through self-trust.

And maybe that’s the difference between my private loyalty and the public loyalties that corrode so much of our common life.

People bind themselves to political tribes, identity groups, movements — and then defend them no matter what rot is uncovered.

That kind of loyalty is indiscriminate.

It’s not tethered to judgment or character; it’s tethered only to belonging.

I don’t know if my way is noble or broken.

But I do know this: if loyalty must deform us, I’d rather be deformed by my faith in a few chosen friends than by the demand that I never betray a slogan, a party, or a tribe.

My loyalty may not always be good, but at least it’s human-sized — anchored in people I know, not abstractions that devour us all.

I’ve never claimed to be a good person. Indeed, I know I’m not.

But of all the ways to be damaged, I suppose this is the one I can live with — and I won’t apologize for it.

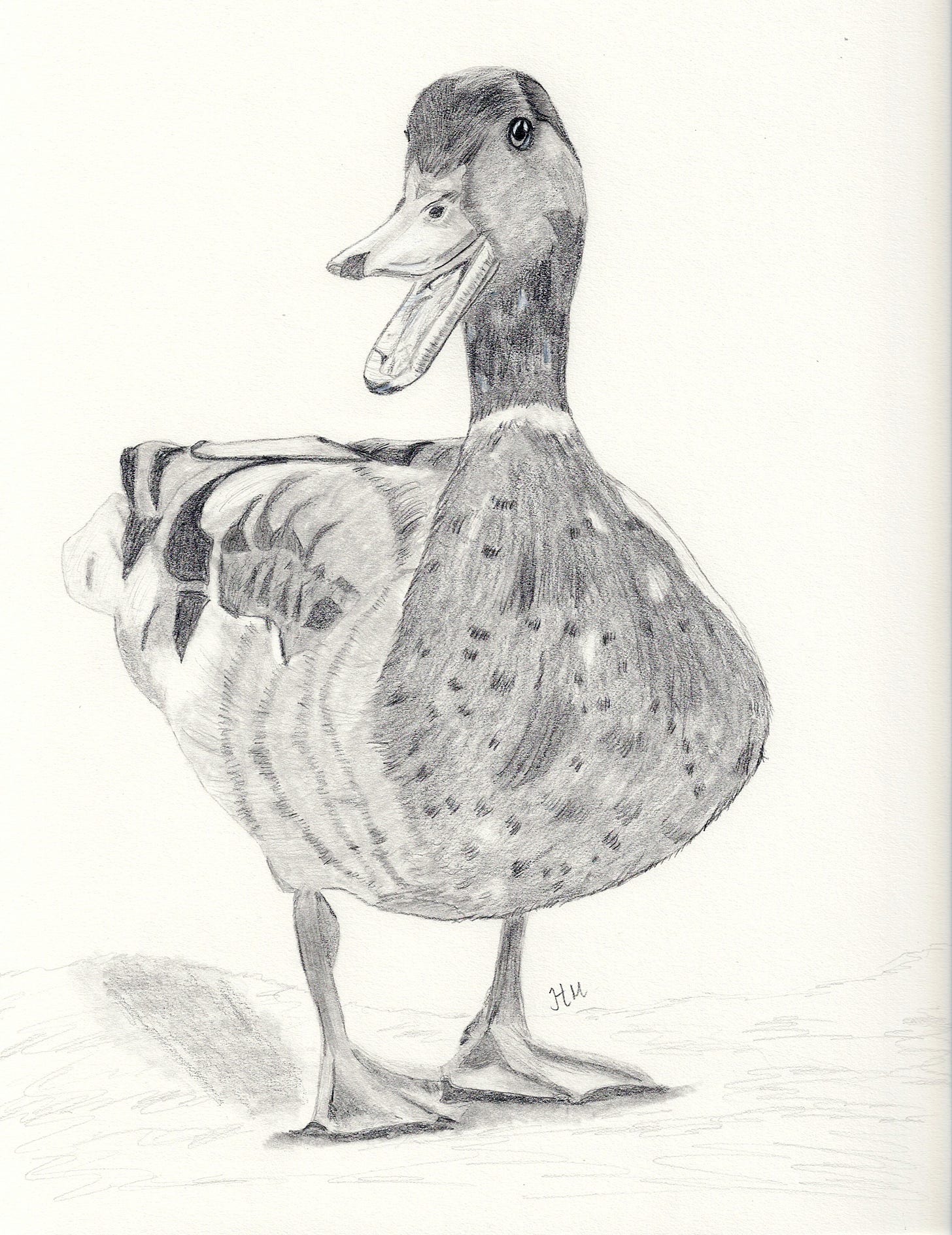

Latest Print For Sale

I’ve just added this fellow — the duck referred to in this post — to my listing of both prints and originals for sale. Prints are $40 plus shipping. If you’re interested in the original, email hollymathnerd at gmail dot com and make me an offer! It’s 8x10 on Strathmore 400 paper. There’s a little white gel pen in the eye but the rest is all graphite on this one. Buy here. Or go here if you’re interested in buying the original. Other prints and originals for sale are also listed here.