Shards of the Self

what social media is doing to us, part 1

Part I: Fragmentation and the Deaths of Complexity and Flexibility

In late 2024, I wrote what I called a Unified Theory of Networked Narcissism — an attempt to answer a question that’s haunted me ever since I left Twitter in the summer of 2022:

Why does social media make us into the worst versions of ourselves?

In that essay, I argued that the problem isn’t just anonymity — though that plays a role. The real damage comes from the convergence of three forces: psychological fragmentation, algorithmic reinforcement, and what I termed emotional whiplash — the destabilizing effect of encountering joy, horror, rage, flattery, trauma, and pop culture references in dizzying succession, all in the space of ten minutes online.

Even healthy people — people with stable egos and integrated selves — experience negative “modes.” Online, those negative modes (like snark, moral superiority, or petty cruelty) aren’t just permitted. They’re rewarded. Reinforced. Amplified. Eventually, they start to dominate.

But for people like me — people with complex trauma and real psychological fragmentation — the effects are worse. The platforms create a mirror world in which the most damaged version of yourself not only gets to speak but becomes your face. Your name. Your voice. Your reputation.

And if you're not careful, your identity.

This new series — Shards of the Self — takes a closer look at the particulars. Each essay will examine one dynamic from the larger theory in greater depth.

This first installment is about psychological fragmentation — not only how social media intensifies it, but how it also simultaneously rewards and programs us to expect an absence of normal, human complexity and flexibility.

We’re trained to mistake personality quirks for hypocrisy, to enforce consistency across contexts that were never, in the full history of human evolution, meant to align, and to flatten others into avatars of ideology.

Let me show you what I mean.

Humans vs. Issues

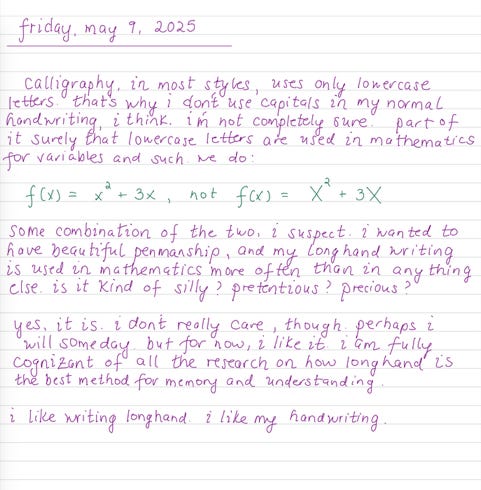

The picture below shows a sample of my normal handwriting. I don’t use capital letters — with rare exceptions. Aside from my signature, the only time I can think of using capitals is when I write a check to my therapist for my copay: first and last name, nothing more.

I write longhand often. I enjoy it. It’s by far the best method for retention and understanding, and it’s the most enjoyable way I’ve found to do mathematics.

Recently, I was reflecting on a conversation I had a few months ago with an internet acquaintance — someone I’ve had many private conversations with, though only online. We know each other’s real identities, addresses, and so on, but we’ve never met. I imagine we will someday, if travel brings us into the same place organically. But that hasn’t happened yet.

She’s also acquainted with

, a close friend of mine, and is a big fan of Josh’s podcast.She understands parasocial relationships.

She’s unusually mature and sensible — a best-case scenario for how these online connections can go.

At one point, I sent her a card. I don’t remember if I drew it or not. I often draw cards, but during my winter depression I drew very little, so it actually may not have been a card, now that I think about it — it may have just been a mailing label on a package.

Whatever it was, she got a glimpse of my handwriting. She commented on it — said how lovely and distinctive it was.

And then she asked, knowing I send cards from time to time, whether I do the same when I send a card to Josh?

She asked because she’d seen Josh ranting on Substack Notes about the lack of punctuation and capitalization in some people’s writing — how it makes him roll his eyes, feel contempt for the writer, and stop reading.

I told her yes, I do send him handwritten cards in my normal handwriting. And if he finds it annoying, he’s never said so.

That was it; the conversation moved on.

Before I go further, I want to be clear: I’m not criticizing her. It was a reasonable question. She saw Josh complain online about something that bothered him. She noticed that I do that very thing. So she asked if I do it with him, too.

In some ways, her question was the height of reasonableness.

It presupposes a kind of integrity — and I mean that word in the older, mathematical sense: whole, like an integer.

Not as a synonym for “honest,” as it’s most often used today, but as a synonym for “cohesive.”

Her question assumed that a person’s publicly expressed pet peeve would also apply in real life.

I found myself thinking about this a few nights ago, driving home from Josh’s house.

We’d spent about six hours together, talking and eating. I brought steaks, which he cooked. It was a life-affirming kind of night — warm and good and real. I didn’t want to go home, but I had to get up early for work, so I made myself.

He walked me out, and we stood talking by my car for so long, with the door open and the interior lights on, that I started worrying about draining the battery.

Josh is a wonderful cook, and a better friend. We talked for hours. We watched a show we both like. When I left, he hugged me goodbye — one of those wonderful, big, real, male-upper-body-strength-fully-engaged hugs — and I drove away smiling, still carrying the feeling of his stubble against my cheek.

He loves my drawings. He loves the surprise of getting one in his mailbox. He knows that my drawings are acts of love — that for me, expressing love is hard, that insecurity is the air I breathe, and that the drawings are how I say what I can rarely say out loud.

Josh is my dear friend. And I matter to him. He doesn’t take love for granted, either from me or in general. If he even notices the oddity of my no-capitals handwriting, he probably just rolls his eyes while smiling. (I haven’t asked him. By the time this is published, I will have.)

I’ve tried, but I just can’t picture him being annoyed or angry while reading something I made for him. I can’t imagine him opening a card, seeing my handwriting, and thinking, ugh.

Even though I don’t use capitals.

Even though he finds that annoying — on Substack.

From strangers.

From writers who aren’t writing for him, in work that isn’t in a just-for-him card.

And yet, her question was perfectly reasonable.

There’s a contradiction there — one that’s hard to articulate. Hard enough that I’ve meandered through this whole setup just to get you ready for it.

Between Person and Persona: Doing the Splits

The contradiction is in two parts, and here’s the first: on social media, people become issues.

We treat expressions of taste or irritation — even trivial ones, like “I hate lowercase writing” — as fixed positions in a personal platform. We assume consistency is integrity. That if you said it online, you must apply it everywhere, to everyone, without exception.

But that’s not how real relationships work.

In real life, we make room for texture.

We hold our preferences loosely, or toss them aside when someone we care about does the thing we claimed to hate. We roll our eyes — not to dismiss, but to affectionately recognize. To say, this is you being you, and I know you.

The very things we claim to be annoyed by become endearing in context.

Quirks instead of crimes.

But the online self — the social media self — is flattened. Abstracted.

It has no warmth, no stubble, no shared meal. No drawings in the mail. It is treated like an avatar of ideology, a bundle of opinions wearing a name.

That’s what she was responding to: the idea that Josh’s public dislike of a trait must (or at least, could possibly) translate to a private intolerance of that same trait in a friend.

She wasn’t wrong to think that way.

Social media trains us to think that way.

It collapses real people into their publicly expressed positions.

And it elevates preferences to principles, where every inconsistency looks like hypocrisy.

But humans aren’t integers. We’re not whole in that way.

We contradict ourselves.

We make allowances.

We love things we shouldn’t, and people who annoy us — and sometimes we do both at once.

And Issues Become People

The second half of the contradiction is just as corrosive: issues become people.

Flat, cartoon people, warped into emotional proxies for something else entirely.

We don’t just over-identify with our stances. We personify them.

We give them faces, backstories, emotional loyalties.

We take abstract ideas and pour our most intimate, unresolved feelings into them — then defend those abstractions or attack them with the intensity usually reserved for family trauma or betrayal.

And it cuts both ways.

Some people hate Donald Trump with the kind of unrelenting disgust they’ve never been able to muster for the actual person who hurt them. They talk about him like he’s their ex — a narcissist who gaslit them, degraded them, humiliated them. Trump becomes their stepfather, their abuser, their smug high school bully, the man who didn’t love them back. He becomes the stand-in for all of it.

Others defend Trump with equal confusion. They don’t talk about him as a politician but as a protective, almost mythic figure — the only one who really saw them. The only one who fought for them. His vulgarities feel honest and familiar. They’re not defending policies. They’re defending a surrogate father, a rescuer they needed once and never got.

That’s not politics. That’s misdirected attachment.

And it’s not just Trump. It happens across the board.

People cry over elections they don’t understand.

They build entire personalities around vague feelings of global injustice.

They call someone “literally genocidal” for using a dated term in a TikTok.

They mistake performance for virtue.

They mistake outrage for moral clarity.

They mistake their identity for their politics — and then weaponize both.

Social media rewards performance, not discernment.

Projection, not perception.

Caricatures, not complexity.

You can see it, painfully, in the rhetoric around abortion.

Some people thunder online about how every pregnancy is divinely ordained — how every fetus is a person with a soul, and how protecting it should be the highest duty of a civilized society. But they say this into the void, not knowing who they’re speaking to — or caring. They’re not trying to persuade. They’re trying to declare. To signal. To play their part.

They imagine they’re speaking against a cartoon villain: the godless whore who “uses abortion as birth control.” That God tenderly chooses which womb in which to place a soul, each done consciously and on purpose by a deity.

But what if the person reading it is a woman who miscarried the results of being raped by her stepfather when she was eleven?

What if she’s just scrolling?

They don’t know. They don’t ask. The script must go on.

And yes, they may care, on some level, about the lives of individual fetuses — just as I care, in a vague and general sense, about the abstract rights of gay people I’ll never meet.

But that’s not the real engine of emotion. When I get my dander up about marriage equality, I’m thinking of people I love. Real people. My people.

And they, I suspect, are not thinking about women like the one who miscarried.

They’re thinking about their people, too. Their imagined audience. Their idea of what righteousness looks like. Their heartfelt belief in a version of a heavenly Father who likes hearing that sort of thing.

Because social media rewards grand narratives that apply to caricatures — not human beings.

Case Study: Free Palestine

Which brings us to the current apex of this phenomenon: the Free Palestine crowd.

Not the thoughtful critics of Israeli policy. Not the people who mourn the horror of war and want a way out.

I’m talking about the true believers — the ones who chant “resistance by any means” with perfect Instagram eyeliner.

The ones who excuse rape, hostage-taking, and the slaughter of Jewish children — not the collateral damage that happens when terrorists hide weapons in schools and dare you to do something about it, but children burned alive in their bedrooms — because “context” supposedly justifies everything, even October 7, 2023.

These are the same people who weep over a man interrupting them in a corporate meeting to “mansplain”.

The same people who treat “microaggressions” in a Manhattan office — where their safety, rights, and career advancement are all legally protected — as oppression too grave to endure.

These are the people who think I suffer from internalized misogyny because I recognize how disastrously over-feminized the West has become — but who will hear no criticism of Muslim societies, hellpits of actual, codified misogyny. Critique those cultures and you’re Islamophobic.

It’s all projection. All emotional displacement.

They are not talking about Palestinians.

They’re not moved by real suffering.

They’re acting out an internal psychodrama — punishing imagined colonizers to avenge imagined harms.

The “cause” becomes a character in their story.

And anyone who complicates the story must be destroyed.

Learning to Resist the Pull

I’ve felt the pull of this distortion myself.

I’ve had to work, deliberately, to keep it from warping my own mind.

When I hear people sneer with disgust at “welfare queens” or lazy freeloaders, my body tenses. I have to remind myself: I was on welfare. I got food stamps. Medicaid bought my hearing aids. State programs paid for the therapy that helped me survive college.

But I also got off. I clawed my way out.

And what they’re angry at — whether they realize it or not — isn’t me.

They’re angry at a system that doesn’t reward escape.

That traps people in loops.

That breaks the link between effort and outcome.

It’s not a personal indictment.

It just feels like one when you’ve lived it.

And from the other side: when I hear someone rant that marriage equality has destroyed society — that gay marriage opened the door to people marrying furniture or livestock — I feel that same defensive flare.

I think of the gay people I love.

I want to scream that they’re not a symbol. They’re people.

But then I breathe.

And I remember that America has always had something like Political Borderline Personality Disorder.

We lurch from one extreme to another, unable to imagine any stopping point short of collapse.

Some people truly don’t believe we’re allowed to fix one thing and stop. They’ve watched a thousand slippery slopes play out.

So no, they’re probably not picturing my friends when they say “the sanctity of marriage is gone.”

They’re not, in that moment, deciding that my friends are personally unworthy of forming a contractual relationship with another adult.

They’re just scared. Which is fine — scared is part of being human.

But social media has trained them to convert that fear into performance — and to expect applause for it.

Some of the Fallout

If you’ve been online long enough, you’ve probably felt it — the quiet horror of watching two people you admire turn on each other in public.

The sickening pang of seeing smart, thoughtful voices reduced to sniping, subtweeting, escalating over imagined slights or algorithmically inflated narratives.

Or worse: the helpless rage of watching someone you know and love in real life be flattened into a caricature — misrepresented by a stranger who has no idea who they are, but who needs a villain to fit their script.

These moments aren’t rare. They’re structural. They’re the inevitable product of a system that rewards purity, punishes complexity, and incentivizes the performance of certainty in a world that runs on doubt.

They are what social media is specifically and deliberately designed to create, to do to us. To hijack our dopamine receptors and addict us to.

Conclusion: This Is What Fragmentation Feels Like

This — all of it — is what psychological fragmentation looks like on a mass scale.

Not just in individuals, but in a culture.

Not just as a trauma response, but as an architecture. As the literal infrastructure of what passes for cultural discourse.

Social media doesn’t merely host our worst selves — it summons them.

It isolates the parts of us that are angry, reactive, paranoid, or performative, and rewards those parts with attention, validation, and algorithmic dopamine. Over time, the fragments take over. The person disappears.

And then it teaches us to expect the same from everyone else — to collapse people into their loudest traits, their most online takes, their worst-day selves. It teaches us to forget that human beings are textured, contradictory, inconsistent — and that these qualities are not bugs, but features. Proofs of our reality.

What we lose isn’t just nuance. It’s mercy.

The mercy of context — for a human being who deserves it, not a years-in-the-making, premeditated pogrom of terror.

The mercy of, “you were tired.”

The mercy of, “you’re more than this.”

The mercy of seeing someone as a person, not a performance.

And if we want to reclaim that — even a little — we have to start by recognizing what we’ve lost.

We have to name the damage.

We have to stop pretending that we’re just “using” social media.

We’re being used by it — broken into parts, fed into the machine, and taught to mistake the noise for a self.

This series is about tracing that breakage — piece by piece, shard by shard — until something like wholeness becomes visible, even if it’s still out of reach.

Or at least until we can see the wreckage clearly enough to stop mistaking it for a home.

And yes, I fully acknowledge the contradiction of posting this on Substack.

No caveats.

I am Bernie Sanders — taking a private jet to bitch about oligarchs and billionaires…and how they’re destroying the climate.

I am Matt Walsh — taking a break from arguing that critical race theory is racial child abuse…to raise money for Shiloh Hendrix.

That doesn’t make me wrong.

It just means I still believe clarity is worth chasing — even from inside the mess.

Part II focused on algorithmic reinforcement, Part III on emotional whiplash, and Part IV on defeating the misery machine.

Well written and fascinating as usual. As a late-comer to social media, I'm not your average user. As you may have noticed, I'm rarely brief in my posts and comments. Earlier this year, I posted something mocking those who think every hand gesture from a stage is a Nazi salute, by a picture from the news featuring David Hogg using such a gesture. Some left-leaning person picked it up to mock me, and it got a ton of comments. Some wanted to "correct" me because I failed to note that a raised arm to the side with a closed fist was TOTS different from a raised arm to the side with an open hand which is TOTS the same as a Nazi salute with a raised arm to the front. I found it amusing because the insults meant nothing to me. Eventually I wrote a post mocking those who mocked and insulted me, rather than engaging them in a comment war. Since I'm retired and well enough off, I don't feel threatened. But, of course, that makes me an anomaly.

Like you, I'm appalled at the deranged people who think they must dedicate their lives and commit felonies to support people they've never met and never will meet and whose suffering they know nothing about and might even be imagined. I worry about how the artificial online world is carrying over into people's real world lives. I suspect you're going to take that up more in a forthcoming essay in your suggested series. I suspect that the lack of an actual body with real feedback mechanisms, including pain, and a real inner drive will prevent the kind of artificial intelligence that people fear and warn us of.

The addictive dopamine hits that the algorithms reward are really nothing new, just intensified by the instantaneousness and ease of reply. "News" has always been designed to try to influence us by appealing to our primal instincts (greed, hunger, fear, fright, and lust) that bypass our rational thought processes. When confronted with real people, it's harder but certainly not impossible to imagine them as imminent threats that must be dealt with without thinking.

BTW, I also write notes, but rarely longer things, in only one case, but for me, my upper case letters are easier and more legible. My parents both had beautiful handwriting. Unfortunately my own is often unintelligible even to me.

Brilliant. Your original essay was probably the best thing I've ever read on social media and psychology, and it's very cool to see your thinking expanding further.

I've been wondering similar things recently, too.

I've worked with a number of people who meet the clinical criteria for personality disorders (BPD mainly), albeit at a level where they are able to make good use of therapy. The first thing you learn (brutally, if you don't catch on quickly) in this kind of therapeutic work is that while you are building trust you must be a "person" in the room first. "Therapeutic neutrality", too much psychic distance, a face that appears blank, etc is absolutely intolerable. Something must be projected and interpreted. Usually that projected "something" will be that this person is bad and/or threatening, and the attack or withdrawal will come. The same thing happens in cPTSD, although it usually looks more terrified than terrifying. All this is to say that interacting online and the flattening and decontextualisation that happens seems to produce the same results, amplifying and normalising pathology.

I have to remind myself often when someone has a go at me online that they are probably somewhere else in time entirely, usually hearing something other than what I have said. Projection arguing with projection, and everyone's unconscious dancing on the keyboard.