The internet is full of big-picture takes on the assassination of Charlie Kirk. I don’t have one of those. Or at least, not yet. Perhaps later, I will. (Edit: here’s my big-picture take.)

This is a small-picture take.

There is almost nothing I despise more than being blindsided.

My therapist calls it childish. He reminds me, often, that life is full of surprises, that control is an illusion, that maturity means learning to tolerate uncertainty.

He’s not wrong. (That bastard is never wrong.)

But he also wasn’t there when my need for certainty was forged. Trauma hardwires a body to scan for threat, to crave predictability like oxygen. And for me, that need hasn’t softened much with age.

I started seeing him not long after I moved to Vermont. He became a shaping presence during my “year of residency” — that liminal year when I had to establish roots before I could qualify for in-state tuition. That meant he was also there when I decided to major in mathematics.

He didn’t steer me — not towards it, not away from it.

But he did make sure I wasn’t fooling myself. Over and over, he pushed me to own, out loud, that my motivation was rooted in unresolved trauma as well as genuine love for mathematics and logic.

Both could be true at once, and I needed to understand what I was doing.

Mathematics is the only place in life where faith has no role and absolute certainty is possible. Not only is proof possible, but without proof — literally, without producing a valid and logically sound document called “a proof” — you don’t have anything at all.

A theorem without a proof isn’t a theorem; it’s wishful thinking dressed up in notation.

That same standard has infected the rest of my life. If I don’t have proof, I can’t trust. If I don’t know what’s coming, I brace for catastrophe.

My therapist frames this as a “distaste for surprise” or a “childish need for certainty.”

I know it’s deeper: it’s the re-enactment of a childhood need that was never met.

My friend

carries the same wiring, though it manifests differently.For both of us, being blindsided is intolerable. We have an explicit pact: never, ever, ever pull a “we need to talk later” on each other. If one of us does have to postpone a conversation, it comes caveated to death. “Josh, I need to talk to you later. It’s nothing bad, nothing you need to worry about, nothing related to you. I just need your take on something solely related to me.”

We’d rather drown each other in disclaimers than leave a single ambiguous gap that the other could fill with dread. It is our emotionally literate version of deep philia, what the Greeks called brotherly love.

Which brings me to my first thoughts when Charlie Kirk was shot.

I watched the close-up video and knew, without question, that he was dead. The shot had struck directly through the jugular. What followed wasn’t blood loss so much as a geyser, Old Faithful in human form.

Even if he’d been standing in the lobby of a blood bank with ten gallons of O-negative ready and a line of phlebotomists waiting with needles in hand, there was no chance.

You can’t transfuse into a vein that no longer exists.

It was instantly obvious that any delay in announcing his death was procedural — a grace period to notify his wife, nothing more. The transport to the hospital was a formality, theater for the cameras and the crowd.

I grew up in the kind of neighborhood where male adolescents universally ended up in the US military or prison, and I’ve had many conversations about battlefield ethics with the boys who made it to the positive half of that dichotomy. Massive blood loss — nowhere near massive as what happened to Charlie Kirk — results in making the sign of the cross and moving on.

Having recognized reality, my first thought wasn’t about Kirk himself but about Josh. I knew that of everyone I love, Josh would take this the hardest.

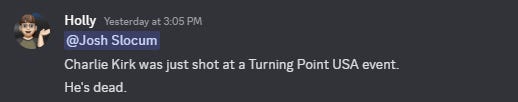

At 3:05, in our private Discord channel, I pinged him and pulled the band-aid off.

He had already been notified by others about the shooting, but not about the certainty of death.

When he replied an hour later, he was still clinging to hope.

By then he was already on his way over for a pre-arranged round of woman-friend-with-a-bad-shoulder-needs-him-to-do-househusband-chores.

So I held back.

I didn’t call him, didn’t force him to accept the reality I’d already seen. I told myself it would be kinder to do it in person, to cushion it with my presence.

At the same time, I knew there was a real chance the news would break before he got here. Once Mrs. Kirk had been notified and gotten a moment with his body, there would be no reason to delay the announcement any longer.

And that is exactly what happened. The moment Josh walked in my door, Megyn Kelly’s screen ticked over to “RIP Charlie Kirk.” It happened at the precise instant that Josh’s voice called out, “Hello!”

I told him. I watched his face drain all color.

I tried to soften it, as girls do — I told him it had been instant. No suffering, no awareness of dying, never any chance of survival.

And here’s where the trauma reflection — the small-picture view — begins.

Because for the ninety minutes or so between my watching that close-up video and the public confirmation of his death, I lived in a split reality.

On one side, livestreamers, YouTubers, and journalists worthy of the former meaning of that word (i.e. Megyn Kelly) were leading prayers, spinning out hope, holding onto the possibility of a miracle.

On the other side was me, already certain of the mathematical reality.

An exploded jugular vein and continued life are a logical contradiction.

In mathematics, contradictions don’t leave room for maybes; they collapse the entire proof. If you assume both A and not-A, the structure falls apart instantly.

Watching that geyser of blood from what used to be Charlie Kirk’s jugular vein was, for me, the equivalent of spotting a fatal flaw in a proof: everything downstream was invalidated.

There was no path forward, no wiggle room, no hope.

It was excruciating to watch. Like fingernails scraping my emotional chalkboard. These weren’t strangers to me, not in that moment — they were people I could feel in my body, torturing themselves with hope.

Each “maybe” and each whispered prayer felt like someone twisting a knife they didn’t realize was already buried to the hilt.

I wanted to grab them through the screen, shake them gently but firmly, and say: stop.

Stop tearing yourself apart.

He is gone.

Nothing you do can alter that.

All you’re doing now is prolonging the agony for yourselves and each other.

But of course there was nothing I could do. I was powerless to change their experience, just as powerless as I had once been in the situations that hardwired me to despise being blindsided.

All I could do was sit there with the unbearable knowledge, watching others torture themselves on the rack of false hope.

Trauma makes you think you can shield people if you just get the timing right — that if you soften the words, if you cushion the landing, you can spare them the worst of it.

Trauma makes you believe that because trauma is unnecessary. Nobody has to abuse their kids or their spouse. Nobody has to commit acts of terror to please Allah.

And nobody has to murder a husband and father for having political opinions they don’t like.

But the same part of your brain that clings to the belief that maybe the past is redeemable after all is just as wrong here.

There’s no gentle way to deliver a jugular wound. No version of reality in which Josh walked through my door and didn’t have the bottom drop out of his world.

All I can do is keep my vow: never blindside, never delay, never leave someone I love twisting on the hook of false hope if I can help it.

Because in mathematics, a contradiction collapses everything — the theorem, the structure, the illusion of progress.

In life, it collapses people. Watching Kirk’s death was watching that collapse happen in real time: proof undone, hope invalidated, no way forward.

Some patch the gap with prayer, others with denial.

I try to face it head-on, even when it sears.

Either way, the contradiction stands. The proof doesn’t hold.

And maybe that’s why I hate being blindsided so much.

Because once you’ve seen the contradiction, you can’t unsee it.

You can only brace for the collapse.

When I become aware of one that’s verified and official, the link to a GoFundMe or other fundraiser for Charlie Kirk’s widow and young children will be posted here.

You're the only person I've been friends with who gets these things the same way I do. The blunt declarations of the tragedy up front are so appreciated. Onlookers, Holly does what she says. When our friend Adam died, that was the first statement out of her mouth when I picked up the phone.

I don't know about you, but for me, this is much better. Get it over with.

Also, really well-written. You can turn phrases.

"Liking" such a post feels so wrong. I suddenly find I want the "concerned/caring" FaceBook reaction.