Return to the Street

emotional apprenticeship from furry monsters

A year ago today, my friend Adam and I were trading texts every twenty or thirty minutes.

He had written a post expressing his joy at President Trump’s win and the return of American patriotism it represented. I published it for him, and he was full of dopamine and adrenaline to find out how it was doing on views.

It got about double of the average number of views that posts on this Substack tend to get, which made him exquisitely happy.

Adam died twenty-six days after that post was published. His obituary is here.

I was dreading today because I knew that the waves of grief would be frequent and intense, and they are. My publishing that post for him was such a special thing for our friendship, and I wish so much he had gotten to enjoy it for longer.

Knowing a sad day was approaching got me thinking about emotions, emotional literacy, and skills for regulating emotion. When someone you love dies, it changes the shape of your interior landscape. The sadness is real, yes, but so is the bewilderment — how am I supposed to hold something like this?

How do I keep functioning while something enormous is happening inside me?

I realized, not for the first time, that I simply didn’t have a lot of the skills that other people seem to absorb naturally.

My childhood internal map for “brutal unfairness” was that it’s rather synonymous with “being alive.” As an adult, that became coldly utilitarian — and not without self-pity, I freely admit — but manageable.

I choose to keep breathing. Ergo, I choose to cope with the reality of extremely unfair things that hurt, and the reality that they will never stop happening.

And, because I am an American who was raised by a combination of my own intuition and television, that led to me thinking about Sesame Street. Childhood TV, for better or worse, was one of the few stable sources of instruction I had.

November 10th is Sesame Street Day, commemorating the day it premiered in 1969.

Sesame Street began as a radical experiment in public television, funded by the Carnegie Corporation and the newly-formed Children’s Television Workshop. The idea was shockingly earnest: use television — a medium generally accused of turning children into decorative houseplants — to close early childhood education gaps, particularly for low-income kids. The creators consulted child psychologists, teachers, and educational theorists, then mixed it all with puppetry, bright colors, slapstick, and songs that lodged themselves permanently inside the human nervous system. (If you have ever found yourself singing “C is for Cookie” while trying to present as a respected adult with a mortgage, you are already part of this lineage.)

The show was also groundbreaking in representation. Sesame Street was set in an urban neighborhood with a multiracial cast at a time when non-white people on television were nearly all entertainers — when characters like Lt. Uhura, on Star Trek, normal people who just happened to be black, were groundbreaking.

But it wasn’t performative or smug, the way “representation” often is today — it was just… normal. Ordinary people getting along, working, talking, teasing, helping, disagreeing — all of them visibly different from one another, and none of it treated like an after-school special.

It acknowledged feelings, conflict, frustration, death, love, and friendship. It treated children as people — not as soft-brained idiots who needed everything sanitized for their protection. It was educational television that assumed children had internal lives worth honoring. And somehow? It worked. Kids actually learned. And adults — if you get enough of them alone and softened up — will quietly admit that they learned things too.

So why am I writing about Sesame Street, besides it being a day of sadness that happens to fall on Sesame Street Day?

Because lately, I have been thinking a lot about how we learn to be human. Particularly about the lessons that those of us who, functionally, had to raise ourselves tend to miss.

When Adam died, there was no instruction manual for how to grieve a friend. There’s no syllabus for “your heart just broke; here is what to do next.” I was back to guesswork and instinct — the same tools I had as a child. Which is probably why my mind went back to a show that tried to teach those things gently.

Sesame Street is, fundamentally, about emotional apprenticeship — about getting angry and then apologizing, about curiosity without shame, about being small in a world full of much bigger things and still finding your place. I didn’t learn most of those things when I was supposed to.

I’m learning them now, as an adult, which is mildly humiliating but here we are. My childhood was chaotic enough that I feel zero shame about indulging childish joys, though I do my best to avoid childish behavior. I sleep with a teddy bear. I buy myself LEGO. I decorate my apartment in bright, happy colors because I am the one living in it, and I want joy to feel physically present.

And I can freely admit that I absolutely love Sesame Street. Some days, especially days like today, I need gentleness that is simple, sincere, and uncomplicated.

My two favorite characters are Count Von Count and Elmo.

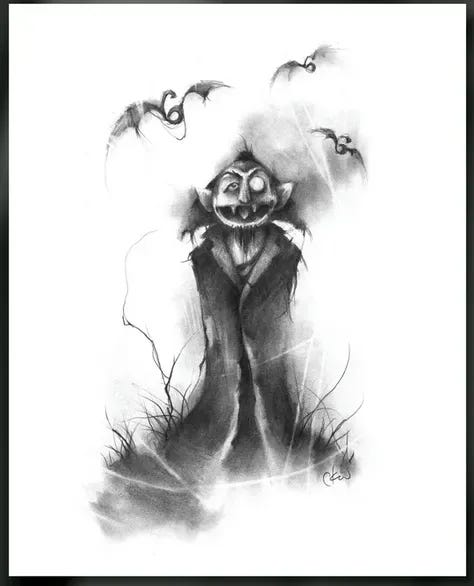

The picture above is of a print done by Chad Wehrle. I love it because it somehow makes Count Von Count look both sinister and adorable — like a tiny Transylvanian CPA who files your taxes and also maybe your soul. He is absolutely thrilled to count anything: bats, apples, existential disappointments, the number of times I’ve sworn today (higher than you’d think).

The Count, obviously, is a numbers guy. He adores counting — not as a dry, boring task, but as a source of pure delight. His laugh — Ah! Ah! Ah! — isn’t evil, it’s ecstatic.

He counts because the world is countable, and that fact alone is wonderful. I relate to this. Numbers were, and are, my refuge. When people were unpredictable, numbers weren’t. You can always check your work. You can always run the calculation again.

There is something romantic about the idea that structure, rhythm, and pattern can make the world make sense.

Here’s the story of Count’s first day of school. Warning: it’s so catchy that you will absolutely find it stuck in your head for the rest of the day. (You’re welcome.)

And then there’s Elmo.

I don’t have a tidy explanation for why Elmo affects me the way he does. I just love that little red monster. Elmo is pure benevolence. He looks into the camera and speaks in second person: Elmo loves you!

And somehow…I believe him. There is no irony in it. No wink. No performance. Just a small creature who means exactly what he says.

When I watch Elmo, something strangely un-armored in me responds.

Something pre-verbal recognizes the tone before the words.

It is embarrassing and also very real.

This song about Elmo is wonderful for the way Elmo just purely delights in the joy of hearing his name rhymed:

And now, because it’s Monday and I need to get back to work, I will leave you with Elmo’s Song.

Because of course I will.

Grief and joy aren’t opposites; they’re twins.

Grief means something mattered.

Joy means something still does.

Sesame Street reminds me that both can live in the same day. Even this one.