Did you know that Atticus Finch was a despicable, unapologetic racist?

Yes, that Atticus Finch.

The father from To Kill a Mockingbird. The one who wouldn’t let Scout say the n-word1, even though it was completely normal among her classmates; who put real time and effort into trying to save Tom Robinson’s life — including facing down a lynch mob. The one who managed to get Bob Ewell’s sexual abuse of his daughter and drunken neglect of his other children into the court record.

I didn’t know either — not until college.

How did a math major end up in a class like that?

No great mystery. I chose my general ed courses very carefully. Math is hard, and despite herculean effort, my early grades in the major hovered around the high C / low B range.

They improved over time. As my skills grew and I figured out how to actually learn, solid B’s became my floor. I earned A’s in Calculus III, Number Theory, and Nonparametric Statistics — which is the kind of statistics where you’re not allowed to assume anything about your data. That experience is a big part of why I believe anyone can learn math, if they put in the work2.

But I always knew I needed as many A’s as possible to drag up my GPA, so I picked my general ed courses with the strategic precision of a raccoon opening a garbage can.

For my required literature class, I chose one focused on 20th-century American novels — correctly guessing I’d already read half the syllabus in my bookworm childhood.

And that’s how I found myself reading scholarly critiques of an award-winning novel — one that has inspired generations of kids to grow up and go to law school so they could fight for the rights of the unjustly accused — only to learn that it was actually a seething hotbed of quietly normalizing vicious white supremacy and racism.

This kind of historical shift is on my mind a lot lately. Americans are very good at taking something once seen as completely ordinary and having it become the very definition of evil.

Which brings me to Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Specifically, Little Town on the Prairie.

Pa Ingalls: Worse Than Hitler?

The events of Little Town on the Prairie unfold during the year when Laura is roughly fourteen, turning fifteen. The book ends two months shy of her sixteenth birthday.

For proper context, it’s important to note that Pa Ingalls is portrayed throughout the series as a devoted, affectionate, and attentive father. The only incident that could even remotely suggest abuse occurs when he whips Laura with a strap once as a very young child—around five years old—for hitting her sister (holy hypocrisy, Batman…). Even this is presented with some level of paternal care: it’s not sadistic, it’s not violent by the standards of the time, and it’s followed by comfort and affection. He doesn’t use fear or cruelty as parenting tools.

In fact, across the series, he is more actively present in his daughters’ lives than many fathers are today, even in an age when “hands-on parenting” is supposedly a societal standard.

Pa had no sons, which was a common rationale in his era for emotional distance from one’s children. But he never used that excuse. He is engaged, encouraging, often playful. He is what many readers would consider an ideal father, at least within the world of the books.

The community of De Smet organizes weekly “literaries”—evening gatherings that serve as a kind of cultural and social outlet on the bleak winter prairie. The first is a spelling bee. Others include a musical evening, a group recitation of patriotic speeches, and a spirited debate on whether Lincoln or Washington was the greater man.

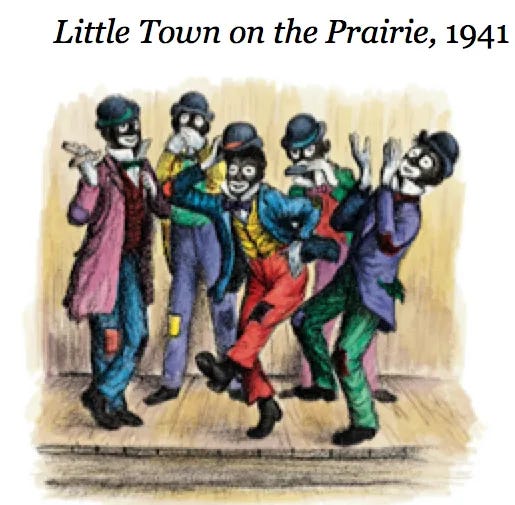

The final literary of the season is a full-length minstrel show, in which Pa Ingalls is one of several men who takes the stage in costume and performs in blackface.

This moment is described in cheerful detail and seen through Laura’s admiring eyes. You can hear it for yourself in the audiobook, from 5:21:01 to 5:25:21, here. The scene is depicted with zero criticism or dissonance in the narrative. In fact, it is one of the liveliest, most enthusiastically described parts of the entire evening.

The deluxe color-illustrated edition of the book even includes a colorful illustration of the performance. It’s all presented as wholesome frontier fun.

That kind of depiction is radioactive in 2025.

We live in an era where a white child dressing up as something dark-colored for Halloween (like a latte, one case I know from real life), or as a celebrity or fictional character with darker skin than theirs, must be carefully instructed by their parents that they absolutely cannot darken their skin with makeup—not even to match the “coffee” color.

Leftist parents have this talk while jerking off their virtue boners, explaining it’s because of the long, ugly history of blackface and how easily such an image can be interpreted as racist mockery.

Other parents might calibrate their explanation more honestly — it’s likely that very few people would mistake it for blackface, especially from a kid, but someone might — and then they can ruin your life. (Someone might ruin your life just for fun, even if they know damn well you’re dressed as a latte.)

Your name would turn up in google with the word “racist” attached forever, and we might get death threats. Your parents might lose their jobs.

Our cultural mania for destroying people over this goes quite far. In one recent case, two California high schoolers were publicly accused of wearing blackface after photos circulated online—only for it to come out later that they’d simply been wearing dark acne-treatment masks. The social media outrage had already gone viral by then, and the students ultimately withdrew from school amid threats and harassment, despite the complete lack of racist intent.

This is how fraught the terrain has become. And yet, Little Town on the Prairie—blackface scene and all—remains a staple, if now a controversial and often censored one, of American children’s literature.

I’m going to make the case that these books are still worth revering, and that doing so isn’t the same thing as endorsing every value they implicitly contain.

But before we get there, we need to honestly examine the racial content embedded in them—how it works, what it meant then, and how it lands now.

The Minstrel Scene in Context

To modern readers, Pa Ingalls donning blackface for a minstrel show lands somewhere on a spectrum—from “oh wow, I hadn’t really thought about this when I read it as a kid” to “serious gut punch.”

But in the context of the late 19th century, when the scene is set, and even the early 20th century, when Wilder wrote it, minstrel shows were not just common—they were mainstream entertainment. They were performed in churches, schools, and town halls. This wasn’t fringe behavior. It was culture.

The scene in Little Town on the Prairie captures that with total normalcy. The town gathers for the final “literary” of the season. The big finale is a minstrel show, performed by local men—including Pa Ingalls—in full costume and blackface.

Laura watches with delight. The townspeople laugh and cheer. The tone is celebratory. There’s no discomfort, no critique, no suggestion that anything might be off. Because in Laura’s world, nothing about it was considered wrong.

What does this tell us about Pa?

That he valued laughter and community. He worked long days doing physically demanding labor, but still found time and energy to rehearse and perform—not for praise, but for the collective good.

He wanted to make people happy. And he did.

It’s easy to forget this, but as portrayed in the books, Pa originally got involved in planning the literaries because Laura was struggling with what we’d now recognize as burnout or perhaps even mild depression. He told the family they needed “some fun to liven us up.”

What does it tell us about the town?

That this was the kind of thing they found funny. That a caricatured performance in blackface was, to them, lighthearted fun. That the racism was neither hidden nor explicitly endorsed—it was simply invisible to them.

When the book was published in 1941, live minstrel shows were mostly gone, but their influence wasn’t. Radio shows like “Amos ‘n’ Andy” still trafficked in the same tropes. Hollywood still featured blackface into the 1950s.

Wilder didn’t include the scene to be provocative—she included it because, to her, it was part of documenting how things actually were.

The stereotypes that minstrel shows relied on—especially the ones casting black people as musical, servile, and clownish—haven’t been widely held in decades.

Ironically, I first learned those specific stereotypes not from the culture itself, but from reading critiques of the Little House books. I already knew some racist stereotypes about black people, the same way I’m familiar with the ones used against white women. (I’ve been called “Karen” for politely asking a produce clerk if there were fresher vegetables in the back.)

But the minstrel tropes? Those were dead to me—until someone insisted I needed to be outraged about them.

So in a strange way, the outrage has kept them alive.

I’m not sure what I think about that.

I can make an argument that the backlash against these books has done more to preserve the stereotypes than the books themselves ever did.

I can also make the opposite argument: that forgetting the past is how you end up repeating it. But if that’s the concern, then surely the answer is contextualization, not censorship.

The Books Over Time

Guess which way our culture has tended to go?

Starting in the 1990s, Little House on the Prairie began appearing on school reading challenge lists for racist content. Ma Ingalls openly despises American Indians3. In one widely reported case, a Dakota mother in Minnesota petitioned her daughter’s school to stop assigning the book after the class read the line, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” Her daughter was eight.

The school refused to remove the book from the curriculum, even after protests—and even after the ACLU threatened to sue the district, ironically on the grounds that removing the book would be censorship. (Remember when the ACLU fought censorship? Good times.)

That incident marked a turning point. No longer could Wilder’s work be treated as culturally neutral or universally beloved.

I think it’s appropriate—necessary, even—for teachers to bring up Ma’s hatred of American Indians, especially if they have any American Indian students in the room. It’s a chance to talk about the tensions on the frontier, the despicable crimes the U.S. government committed during the era, and what efforts—imperfect though they are—have been made toward repair.

What I don’t think is appropriate is censoring the books or removing them from classrooms altogether.

In 2018, the American Library Association took a more public-facing step: it renamed its lifetime achievement award in children’s literature, which had been known as the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award since 1954. The new name, “Children’s Literature Legacy Award,” was, in the ALA’s words, “chosen to better align with the organization’s stated values of inclusiveness and anti-racism.” The association emphasized that this wasn’t a book ban, nor a denouncement of Wilder’s contributions, but an acknowledgment that her work includes “expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with our core values.”

The decision caused an uproar. Some saw it as historical erasure or textbook cancel culture. Others applauded the move as long overdue.

The books remain in print, on library shelves, and in circulation—but Wilder’s pedestal is gone.

And this reflects a broader shift. Some school districts have quietly pulled Little House from their required reading lists. Some libraries have moved the books out of the children’s section and into the “classics” or “historical” shelf, where they’re still accessible but less likely to be handed to a young reader without framing.

Other educators, in my view, have taken the least-bad approach: they still teach the books, but with added materials that frame them within the historical context of the era—including the concept of “manifest destiny,” and its long shadow.

From the Other Side (Sort Of)

I want to be clear up front: my experiences with racism have been mild. I was poor white trash—that’s the right term—in a mostly black neighborhood as a kid. I got a fair amount of crap for being white, but it didn’t bother me all that much.

Partly because, even as a kid, I implicitly understood that being white was “better.” I wouldn’t have used that word at the time, but the understanding was there.

And partly because every kid got crap for something. The one who was worst at school got called stupid. The kid with crooked teeth got called Sharkbite or Snagglemouth or some variation thereof that I’ve forgotten. In that context, being the white kid wasn’t a deep trauma. It was just one more insult in circulation.

It was only later—early adolescence, maybe—that I recognized my particular insult as racial. And even then, it didn’t burrow into my self-worth. It didn’t reshape how I saw myself or what I thought I could do. It just…registered.

Something in my brain just saw it, nodded, and perhaps said, “Noted.”

I know I’ve never been followed around a store or been afraid of a cop because of my race. But I’m also not convinced that’s always a huge, unmanageable crisis.

My experience of identity friction is closer to how I’ve experienced sexism: it complicates how you're perceived. It introduces doubt and second-guessing. Sometimes you don’t get to know whether your treatment would have been different if you were male—or white.

That ambiguity is its own kind of psychological noise.

I’ve been the woman wondering if I was a diversity hire. That sucks. But it sucks one hell of a lot less than not getting hired at all.

And I’ve been in meetings where someone literally said, “We’re not interviewing white men this time.” That wasn’t subtext or innuendo. It was policy; saying, as the kids say, “the quiet part out loud.”

And I still believe in colorblindness. I know that’s considered a heresy now, but I don’t give anything resembling a fuck. I believe in it the same way I believe in treating people like adults and using your blinker at a four-way stop.

But here’s the part that clarified things for me.

I asked myself: how would I feel about Little House on the Prairie if I were black?

And for the first time, I found a real parallel—not a thought experiment, not a performance of empathy, but an actual thing in the culture that lands on me the way blackface might land on someone else.

Drag.

Not drag as personal expression or queer history or art. Not drag as a genre. But the version of it that shows up in mainstream entertainment—the cartoon version. The high-pitched baby voice. The exaggerated sexual submissiveness. The hyperfeminine bimbo shtick played for laughs.

Not all drag queens do this. Not all transwomen do this. But plenty do. And when they do—and when it’s cheered, centered, praised as brave and beautiful—I feel something twist in me.

Because I don’t see myself reflected in it. I see myself parodied.

And I see everyone around me acting like it’s fun. Like it’s affirming. Like it’s some kind of progress.

It pisses me off.

It makes me lose respect for people who enjoy it or perform it or fail to see what’s offensive about it.

If they think that’s a celebration of femininity, what in the everloving fuck do they think femininity is?

But here’s the thing: I also know it’s not real harm.

I’m a grown-ass woman. My feelings are my responsibility. I can vote with my feet—I don’t go to drag brunches or to any place that I know hosts drag shows. I can vote with my wallet. I can speak up about the bullshit excesses of transgender activism and the ways some of it erases or ridicules women.

If I do that, then I’ve done what I can to register a protest. I’ve taken action against something I find degrading or annoying.

But I also stay clear on the difference between annoyance and harm.

Sexist stereotypes aren’t the same thing as sexism. I know that. But my take on it—treating stereotypes as red flags, not prison bars—is more empowering than most of the frameworks I’ve seen. It’s what’s kept me mostly out of victimhood, and mostly out of the drama triangle, at least on this stuff.

I wouldn’t presume to tell black readers how to feel about Little House.

But I do think it’s worth noting: I didn’t even know those minstrel stereotypes existed until someone told me I was supposed to be outraged on someone else’s behalf.

That says something.

It’s one of the reasons I think the books should stay in circulation: not to be celebrated blindly, but because they open doors for this kind of reckoning.

If we let them.

And maybe what it says is this: context teaches.

Outrage repeats.

I do not believe in giving the word mystical power and would use it if appropriate — i.e. discussing To Kill A Mockingbird in person. But if I say it in an email, many spam filters will eat it and readers will never see it.

My series, How to Not Suck at Math, takes readers on the same journey I went on myself, starting with counting.

I was born here. I’m a native American. So is everyone else who was born here, melanin levels aside. That’s why I say “American Indian”.