This is paywalled, so housekeeping first.

This is the sixth edition of a creative writing feature for paid subscribers, who are also able to comment on this post (and most posts). If you would like a paid subscription but can’t afford it, send an email to hollymathnerd at gmail dot com and I’ll hook you up with a free year.

Context: since COVID started, I’ve offered free homeschool consulting. Mathematics turns out to be the reason many families who would otherwise be comfortable homeschooling choose not to do so—a commendable terror of not doing right by their kids. By providing help choosing resources and a solemn promise to step in and teach if they get stuck, I am now personally responsible for four local families deciding to start homeschooling. One of those families referred a friend to me, a teenage boy who simultaneously has severe dyslexia and genuine talent for mathematics. The parents asked me to help him because he was struggling to earn grades that reflected his ability. He understands the mathematical principles with ease, but struggles intensely with the aspects of mathematics that, particularly under Common Core, require reading and writing.

Link: I have previously written my thoughts on Common Core mathematics.

Jack’s Light Bulb Moments

Jack laughs a little every time I say “rational functions.”

The third time, I ask him what’s so funny.

“Well, I mean, all of math is rational.”

It hits me then that Jack uses the word “rational” in the way most people do—to mean calm, sober, based on reasons and not on feelings.

The first light bulb moment comes when I explain that “rational” comes from “ratio,” writing the word on my white board in blue, all caps, and underline the “ratio” in green.

I color swap constantly, a cheap trick that works, at least for him.

The part of his brain that can force itself to read correctly—with enormous effort, and never for very long—understands each color as a separate entity, so he gets the constant benefit of whatever “starting over to read a new thing” energy he has available.

The constant color changes make it easier for Jack to follow, but it’s also funny as hell. I remind myself of Data, from Star Trek: the Next Generation, hands moving in a blur as I swap pens as fast as I can.

Yes, I clarify. All of math is rational, which is why we love it, but rational functions all involve a ratio of one function to another. Some function related to another function, and their overall relationship provides a mathematical description of something or other.

I watch this sink in, and his face reveals his feelings in a quick, patently obvious succession.

Like most teenage boys, he thinks he’s fully mysterious to adults, but I can easily observe his emotions.

He laughs at himself for missing this and then—holy shit!—realizes that this just might help him with his real struggle, these motherfucking word problems.

The hope is palpable, pupils dilating and nostrils flaring as he takes in a short, anticipatory breath.

It takes all my self-control to pretend I don’t notice his excitement.

Jack’s enthusiastic cooperation matters more than everything else, so it’s imperative for him to continue to feel like he’s significantly cooler than the weird, dorky woman with the Christmas tree full of Star Trek ornaments whose apartment his parents have sentenced him to: 90 minutes every Monday afternoon, forever.

The next seventy-five minutes will be frustrating for both of us, but the second light bulb moment will help a lot.

The third one will leave me struggling not to cry and him grinning like a little boy on Christmas morning.

The hope, desperately needed, carries us.

His homework is ten word problems, his nightmare of all nightmares, and they’re terribly written, as if this assignment wasn’t tough enough for him.

They’re so badly written, in fact, that I can’t decide whether I’d prefer to give the writers a beating or a copy of Strunk & White.

Some of the problems use the same instructions: “provide your answer in terms of….” to mean very different things in different problems.

Some of them have extraneous information, but for maximum confusion, using numbers.

“How long will it take if Sally leaves two hours early to pick up three pizzas to split among the four workers?”

The two hours matter. The three pizzas don’t. The four workers do, but not as relates to the pizza.

Understandably, it takes a dyslexic kid several slow, painful re-readings of the problem to be sure.

We discuss the first problem at length, as I’m trying to understand what his brain picks up. I ask an obnoxious number of questions, writing his answers in various colors.

The easel that holds my white board takes up a third of the available floor space, and I swap from marker to marker with every step in the problem.

He has to read a story, figure out how the story relates to a rational function, set up the problem, and solve for some unknown.

“What should our X be? What are they asking us to find?”

He reads the problem again to make sure he understands this. All those annoying, obnoxious sentences rattling around, confusing with their shades of meaning, while the clarity of the numbers, normally a source of solace, is made frustrating because they’re hidden in plain sight.

“Forget about the second half of the problem for a minute. What’s the first basic formula that jumps to mind just for the question of how fast someone goes when they’re paddling down the river?”

The easel wobbles a little when Jack rolls back and forth in my office chair, thinking. He has to close his eyes to make himself block out the reading and think about the mathematical relationship.

When this one is well and thoroughly solved, with good notes (mine) that I will laminate for him when he’s bundling up to head back outside, I glance at the clock and realize: we’ve spent half our time on one problem.

This isn’t the end of the world; he fully understands that one problem. But I take a minute to read all ten problems, to decide what to spend the rest of our time on most fruitfully.

It hits me, then—my mind has been on a calculus track. Calculus is the mathematics of change, applicable to almost everything.

Jack is destined for calculus, but he isn’t there yet. I am overcomplicating this.

His ten problems actually are only three problems, with slight variations.

I make a big show of looking at the clock.

“We’re already short on time, so I’m going to do what a tutor is never supposed to do, Jack. I’m going to show you the easy, fast shortcut. But you can’t tell your teacher, ok? And for sure do not share this with your friends because if they figure it out then they’ll all be using this shortcut, and then she’ll get really pissed.”

His eyes light up; he has the typically overloaded schedule of a college-bound high schooler.

Shortcuts are gold, and keeping a secret from the authority is extra-shiny gold.

“All you really have to do to solve these word problems is figure out the patterns. They’re the same three patterns, over and over with different details. Once you have the patterns you can memorize how to set the problems up, and then you’re good.”

He doesn’t really believe me, so I prove it to him.

The first pattern, I show him, is that of one person doing the same thing under two conditions. Joe drives to work both in and out of a construction zone. Emma paddles on a river both upstream and downstream.

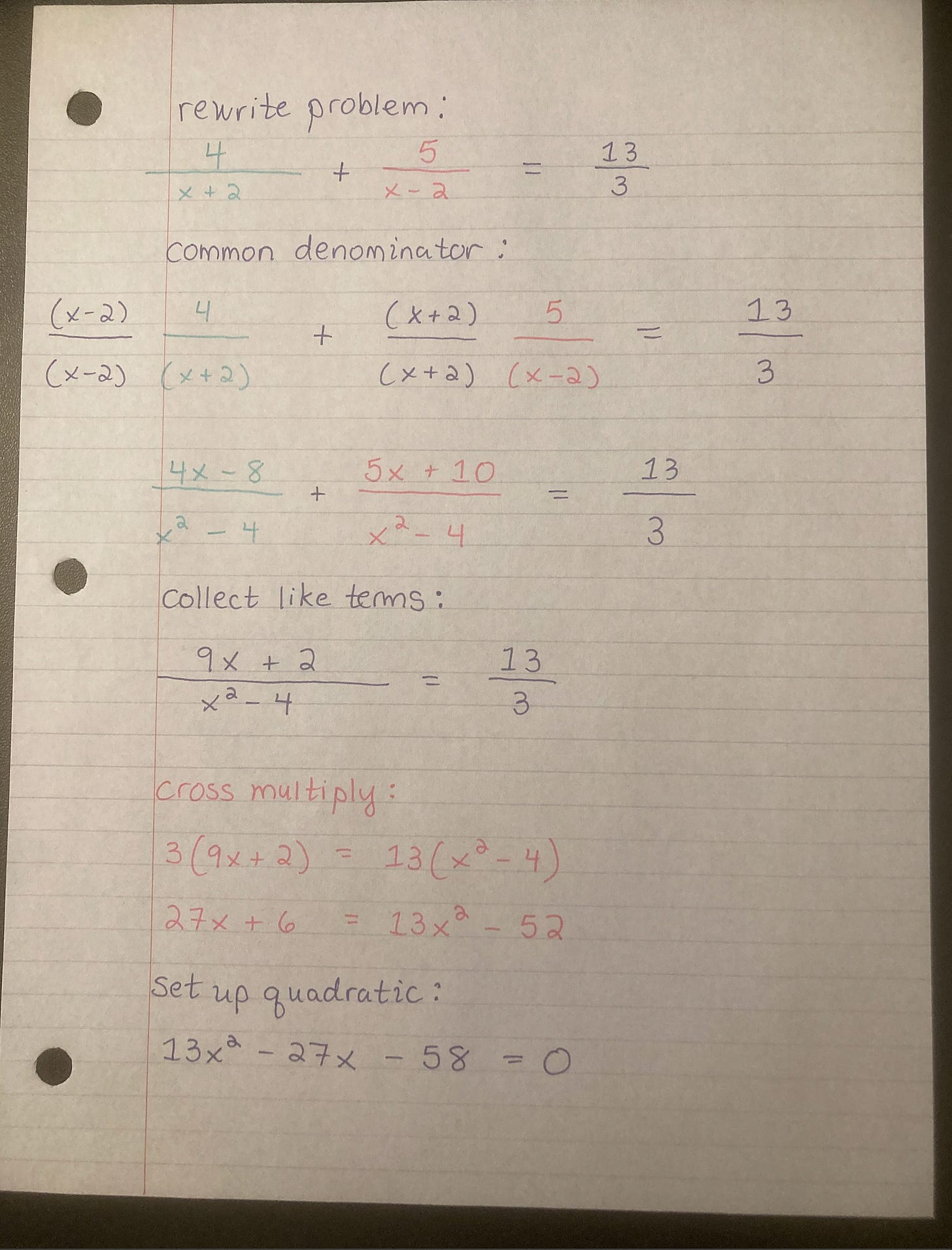

I make colorful notes and copy down the example problem, step-by-step.

Then I show him the other two patterns, for mixtures and blends—how much pure onion powder do you add to a 75 gram jar if you need to end up with a blend that’s 20% onion powder? And combined work—if Maria can paint the room in 4 hours alone and David can paint it in 3 hours, how long will it take if they work together?

He smiles as he marks the problems left to do with a code of his own devising, to tell him which pattern to use. He asks me to check, and indeed, he has them all coded correctly. He will be fine, I assure him. He knows just what to do. The second light bulb is glowing.

We’re almost out of time, so I turn on the lamination machine and start putting my notes into the plastic sheets.

This is normally Jack’s time to start re-loading his backpack, putting layers back on, activating charcoal hand warmers.

I’m sitting across the room, on the floor, feeding notes into the machine, keeping one finger under the output side to guide the sheets into a neat pile.

Instead of starting to pack up, he just sits there, staring.

“Jack—y’ all right?” I finally ask.

He shakes his head a little, coming out of his reverie.

“I just realized something,” he says. “Reading stuff, I mean, reading not-math-stuff, is finding patterns too. There has to be a way to do this for everything. Like—okay, like, for history class, I never read that shit but my mom reads it and tells it to me verbally. Maybe I can find patterns for that stuff too. Like I think for history class reading stuff, maybe the pattern is ‘someone did something to somebody else’ and then ‘someone else responded by doing this other thing’.”

He goes silent again.

“Yeah, I think—I think I can do this. I think there are patterns for all my non-math school stuff. I bet I can find a lot of them.”

The look on his face is that of a very little boy who has just been told that Santa Claus left his best present outside, in the barn, and knows he’s getting a pony.

I activate every shred of self-control that I have access to.

In a split second, I realize that it will not be enough.

I reach into the marrow of my bones and grab my emergency supply.

Because I must not cry.

“Damn,” I say, laughing. “I like that. Turn the rest of school into math, as much as you can. When I said before that math was a superpower I meant for things like making computers obey you, but I bet you can use it to kick history’s ass, too. Cool.”

He smiles, just a little, then shakes his head again.

He packs up to go.

The door closes behind him, and I cry all the way through sending his parents the post-session email.

My life is not particularly easy, in some ways.

Some days are bad in ways I’ll never write about, and some days the demons are fully in control.

But the good days are glorious.

Jack’s light bulb moments made this a very, very good day.

Your paid subscription is reducing my student loan balance, and I really, really appreciate it. Thank you!

Whenever I've heard the term "creative writing" I've always immediately assumed it meant fiction. It finally occurred to me as I was reading this that there's no logical reason "creative writing" couldn't be nonfiction as well. I'm left hoping this piece is at least partly based on one of your actual tutoring sessions. Events that beget happy tears can be so few and far between, so I hope this one was something you actually got to experience. If it wasn't, you're a skilled enough writer to make me believe you did.

Gave me a few tears