This issue has lots of pictures, so your email client may not handle it well. You can also read it at the Substack website.

This is paywalled, so housekeeping first.

Housekeeping: comments are open for paid subscribers, as they are on most posts. Paid subscribers also get my creative writing posts, which in January will include a short story of the horror genre and a novel excerpt. Email hollymathnerd at gmail dot com if you can’t afford a paid subscription.

One Benefit of Careful Shopping

Being desperately poor, which I was for a long time, made me hyperaware of price cycles. I bought Christmas wrapping paper each year on January 3 or 4, knew exactly when Michael’s and other art supply stores put drawing supplies on sale, and otherwise stretched my meager dollars as far as humanly possible. One thing I learned is that if you want something unique or collectible, July and August are the months to shop. The closer we get to Christmas, the more prices go up.

So I give myself a careful budget in the summer and start my Christmas shopping in August. This year, my budget ended up being too large, because I got so many amazing foliage pictures during October. Foliage pictures are wonderful gifts for people who don’t live in New England. (In Mississippi and Alabama, where I mostly grew up, “autumn” is the four hours on the Monday before Thanksgiving when the colors change. If you’re very, very lucky, it stops raining for thirty minutes out of those four hours. My friends in the South absolutely adore these photos.)

This year, in a stroke of great financial luck, I got some really stunning foliage pictures during October, and Amazon had some good deals on frames. My Christmas budget thus had some extra room. I saved some of it, but I made myself buy one nice gift, just for me.

This wasn’t easy. Trusting that desperate poverty isn’t a few seconds from re-taking my life is a huge challenge. But I did it anyway, and I’m glad.

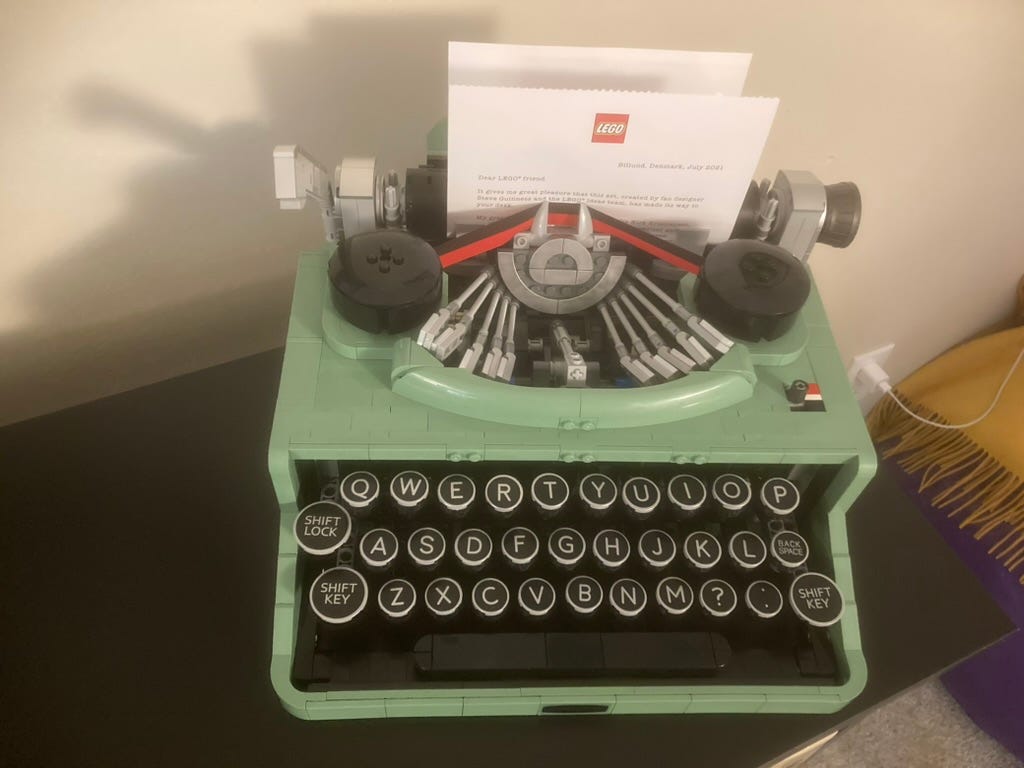

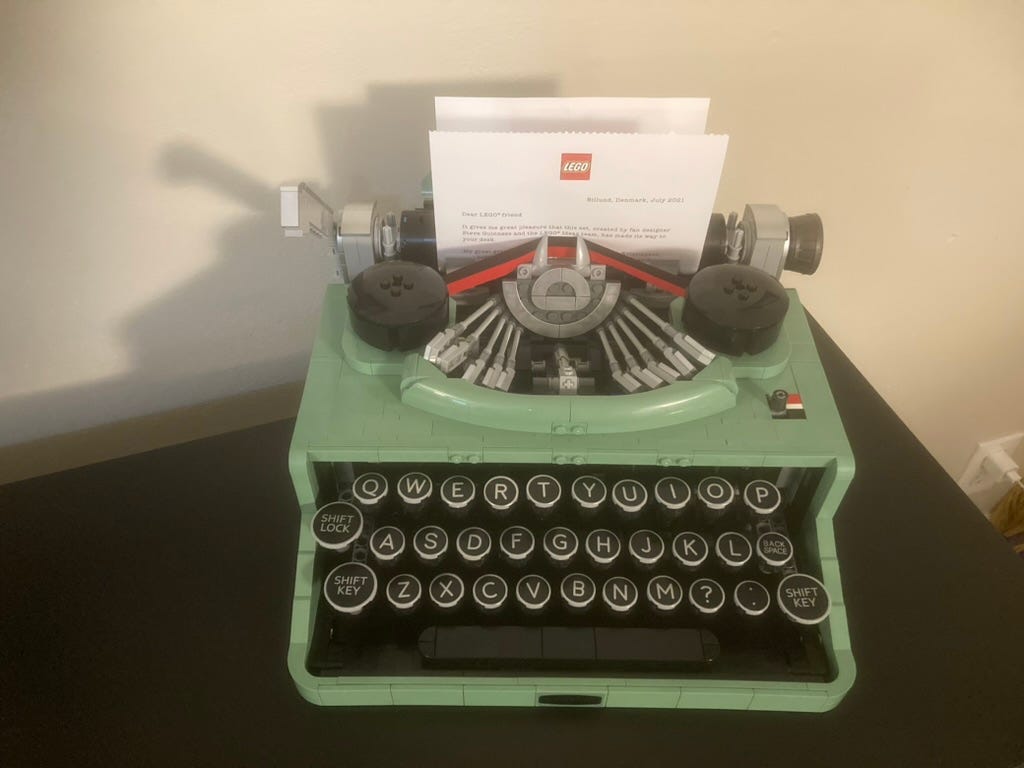

I bought myself a LEGO set that makes a vintage typewriter—one that has both keys and a carriage that move.

A PTSD Tool I Didn’t Expect

The gift I bought myself turned out to provide a helpful tool for PTSD progress, in a way I never could have predicted.

A Lasting Legacy of Child Abuse

When children are very young, their parents’ emotional attunement sets the stage for their entire lives.

When an infant, baby, or very young child is in distress and their parents provide comfort and helpful attention, ending the distress, the child’s developing psyche, mind, and brain learn important lessons:

Distress is not permanent.

Fears are usually unfounded and don’t have to be immediately acted upon.

Suffering doesn’t last forever.

Things are sometimes bad, but they get better quickly, because the world is a fundamentally benevolent place.

Problems are temporary, and solvable.

It is safe to not panic. Terrible things don’t happen just because a situation feels terrible.

Children with caring parents develop the ability to tolerate frustration and work through problems. They do not have to convince themselves that problems are solvable or rationalize their way through not panicking. Their nervous systems are “programmed,” for lack of a better word, to deal with the realities of a problem, without the additional difficulty of a ton of emotional baggage attached.

As the child grows and becomes capable of reason, the parents teach the child how to solve their own problems. The child is able to learn these lessons from the parents in large part because the parents spent the first several years of the child’s life serving as a kind of reassurance dispenser—a secure base from which they can gradually wander farther away, without fear, knowing the base is always prepared to receive and protect them. Why would you not trust those people to teach you how to be like them—safe, competent problem-solvers who can be relied upon?

When a child is neglected, they never learn these lessons.

When a child’s distress brings violent attention, or the parental reaction causes pain in other ways—such as verbal or emotional abuse—their nervous system goes in the opposite direction.

Frustration becomes a cue that something terrible is about to happen and it’s time for fight/flight/freeze mode.

Therapists call this “limited frustration tolerance.”

And yeah….it’s a thing.

Or, as I would say to my friend who understands these things best if he wasn’t too sick to call and bother him presently…God Al-fucking-mighty, is it a thing.

Mindfulness As A Key Tool

I’m not particularly skilled at this (yet), but with a longstanding mindfulness practice, sometimes I can simply notice my experience.

When my frustration tolerance is almost used up, I can notice what’s happening now, at least sometimes.

The top of my head feels tight.

My heart rate increases.

My breathing slows.

I become hyperaware of my environment.

My eyes sting, and if I want to refrain from crying I have to focus my self-control in that direction at once.

Panic and self-fury, that I let my guard down and didn’t expect whatever is going wrong to go wrong, rear up.

Awareness of how childish and ridiculous I’m being is never far away, of course. But this presents its own dangers. If I let those self-judging thoughts progress too far, my ability to deal with whatever is frustrating me like an adult vanishes and the situation quickly spirals.

Usually, I have to walk away, take deep breaths, and spend precious time and energy reassuring myself.

How the Typewriter Helped

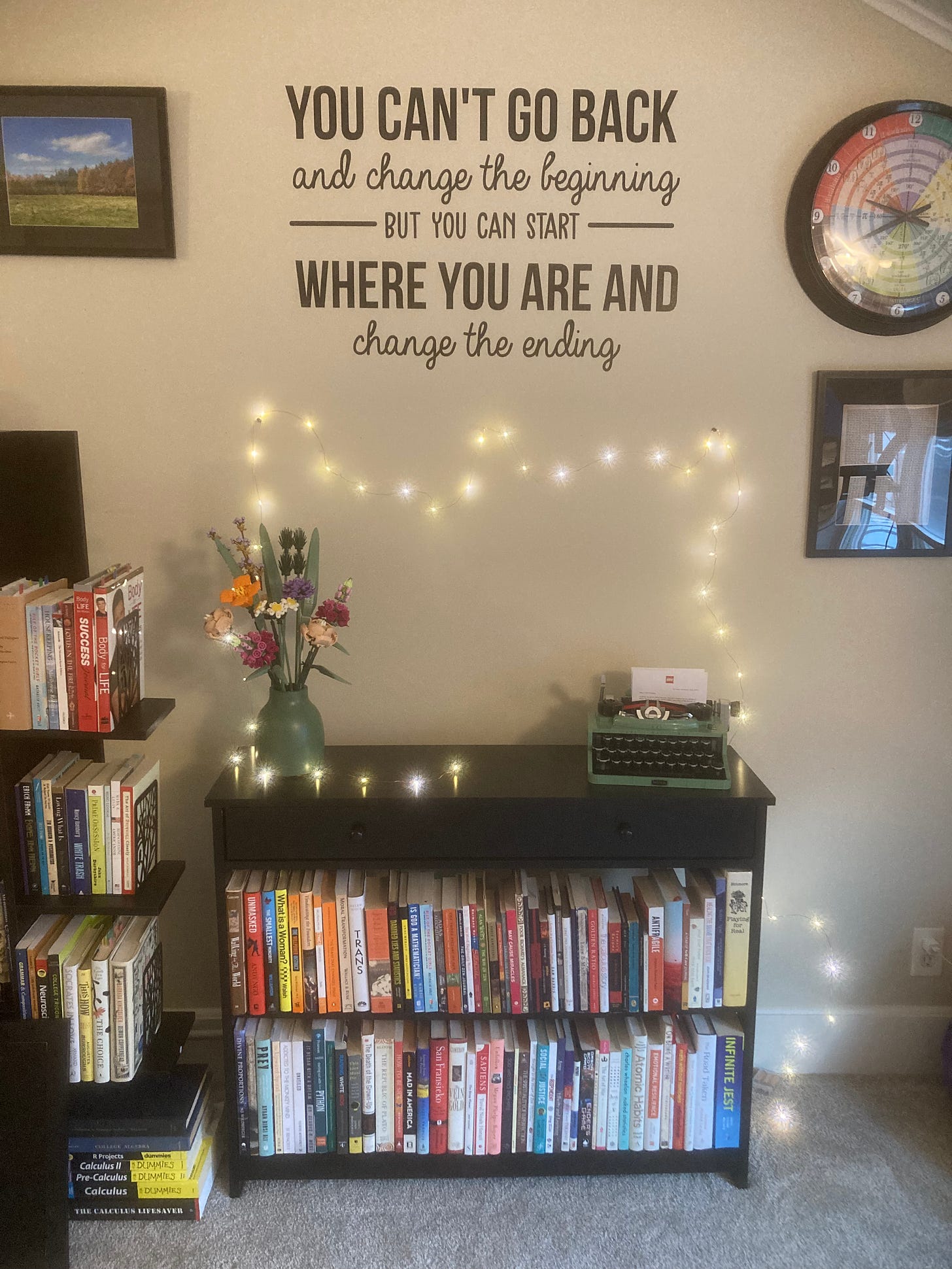

This was the most complicated LEGO build of my entire life. It had over 2,000 pieces, but it’s fairly small. A LEGO build of 2,000 pieces is usually decent-sized. The Christmas village set, with a two-story house, a light-up tree, a chimney that Santa can go down, and a huge variety of other small details to make it special, has fewer than 1,500 pieces. The LEGO flower bouquet in the picture (the flowers in the vase to the left of the typewriter are also LEGO) has 750 pieces.

The typewriter has about three times more pieces, but is smaller.

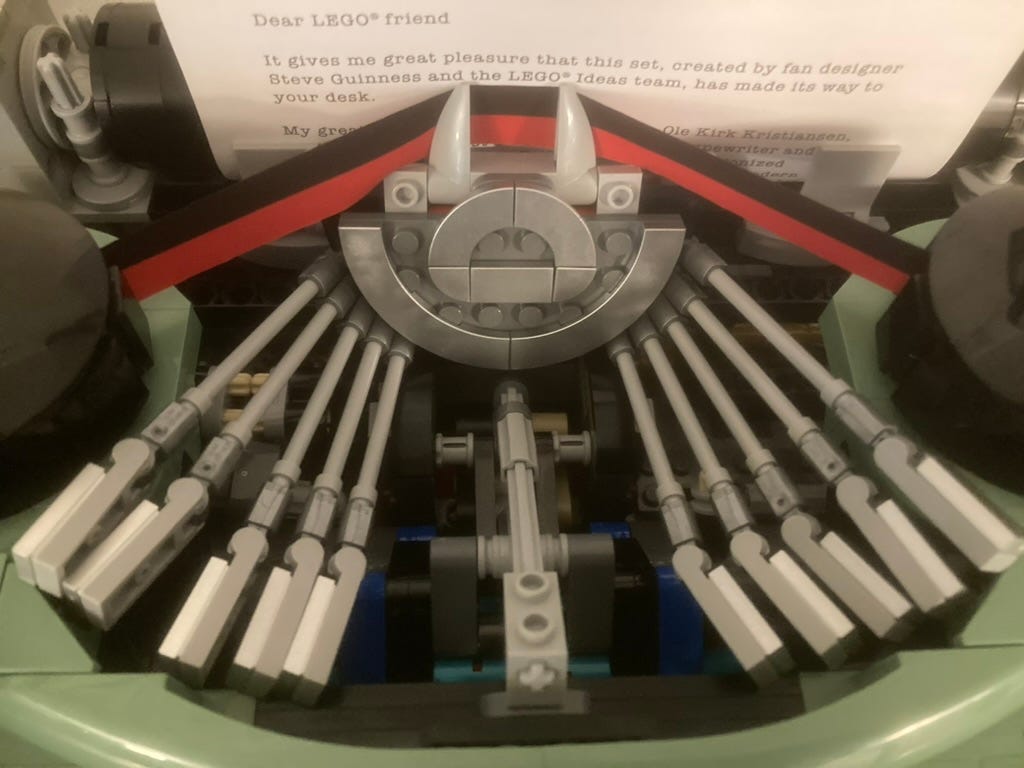

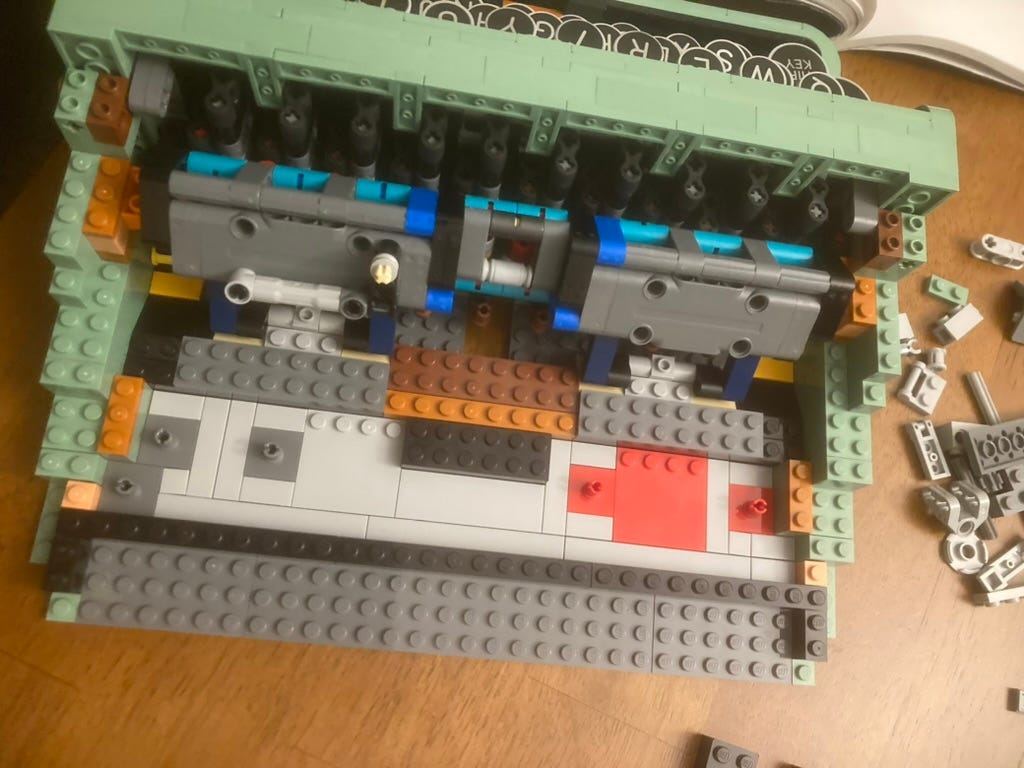

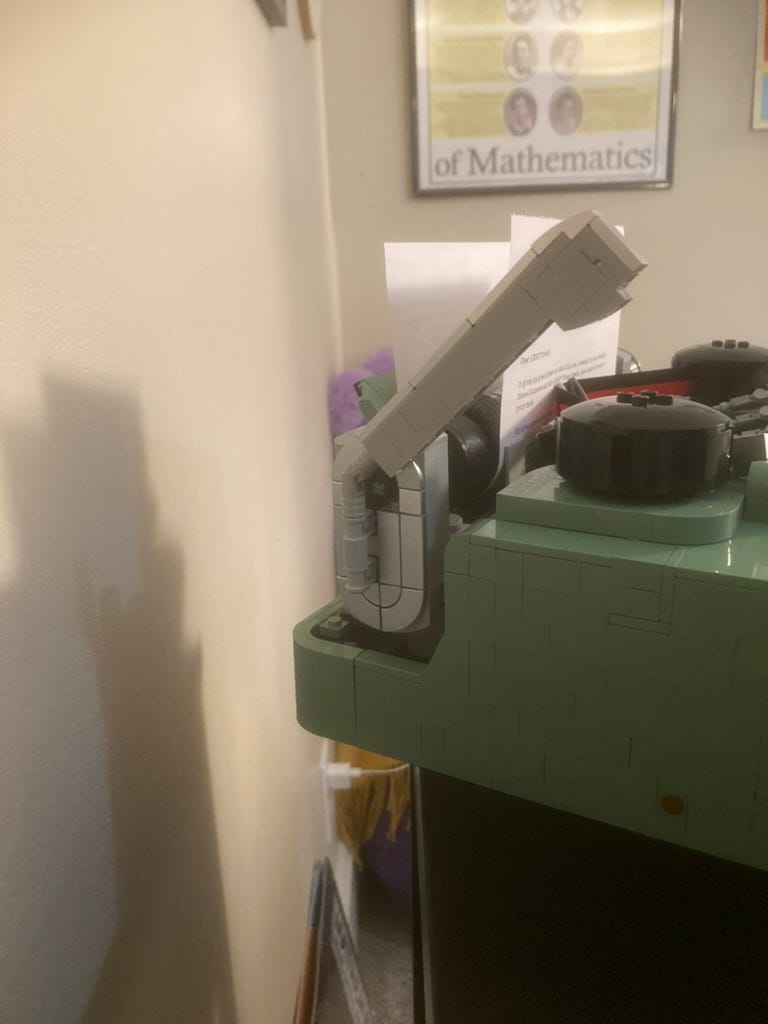

This is because the intricacies of the typewriter are astonishing complex, mostly to ensure the carriage is actually movable. The video is from midway through the build, when I saw how the moving parts would work. (Below are some progress pictures, followed by some pictures of the finished piece.)

It took me about 26 hours to finish, but I’m not sure how long it would have taken most people. I had to start over quite a few times, since there are many easy ways to make mistakes in the initial stages, and I made them all. Repeatedly.

Over and over and over again, I reached a point where two pieces were supposed to touch, but they had a gap.

Or a point where a particular piece was needed, but it had already been used.

Or a point where it was supposed to match the picture, but didn’t.

I started over so many times that it’s embarrassing to admit.

Twenty-six hours, people.

Over and over and over and over and over again, I noticed the internal mechanism of panic rearing up. Frustration mixed with vicious self-blame—it is literally just a toy, what the fuck was I getting upset over, what the fuck was wrong with me?

But I caught it. Each and every time, I was able to notice it, respond with self-compassion, take a short break, and return.

If frustration and PTSD skills were the sort of thing that trainers designed gym workouts for?

This LEGO build would be the equivalent of a marathon.

And I finished it.

I won.

Happy New Year, y’all.

Picture Gallery

Your paid subscription is reducing my student loan balance. Thank you!

Share this post