Honest Coverage of Fetterman is Not Ableist

real talk about disability, accommodations, and fitness to serve

Edited to include a statement from the company that provided the captions.

The Pennsylvania Senate race is between Dr. Oz, a television personality about whom I know almost nothing—though I have a vague mental association of him with Deepak Chopra and other people who push woo-woo health ideas—and a man named John Fetterman. I know nothing about Fetterman except that he had a stroke in May. Since he started doing political appearances using a device similar to one that provides closed captioning, people have been comparing his situation to that of a deaf person who uses closed captioning, and calling out any doubts about Feterman’s capacity as blatant ableism.

I’m not proud of this, but I pay so little attention to politics in parts of the country that don’t interest me that I wasn’t even sure who was the Republican and who was the Democrat until I watched their debate early this morning. My only interest in this race was sparked when podcasts I normally listen to started citing responses to Fetterman, post-stroke, as an example of “ableism.”

What made me decide to watch it and weigh in was this piece on Bari Weiss’s Substack this morning, citing Fetterman’s performance as tragic evidence that he is unfit to serve and media narratives about ableism and disability representation as bullshit.

So, I watched it. My take is below, but first some context.

Why I Am Interested in Disability (and Specifically in Closed Captioning)

I am deaf. Many people hear “deaf” and think that it means “what’s a sound?” In our technological age of powerful hearing aids and cochlear implants, this is almost never what “deaf” actually means. In my case, it means that I am hard-of-hearing to the point that I require technological help to use the phone, which is the usual standard that people with hearing loss use to differentiate between hard-of-hearing and deaf. Thus, I use the word “deaf” to describe my state of hearing.

With hearing aids, I am able to use the phone and participate in most conversations. The key word there is “most.” I struggle mightily with accents and when more than one person is talking. I use the auto-captioning feature on Microsoft Teams to get written records of important work calls. I use captioning on all TV shows, movies, etc., that I watch, and read lyrics to all new music, and otherwise use a mixture of accommodations to help me anytime I need to take in new information by ear.

I also suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, a consequence of longterm child abuse when I was a kid and having been raped as an adult. I have, at times, required accommodation for both these disabilities.

What Is Ableism?

Ableism, in my view, is a type of prejudice that prizes a state of normal health and/or capacity over a state of disability when the disability in question can be reasonably accommodated such that it does not result in a lack of ability to perform the job or task in question.

A few examples of what is and is not ableism.

Ableist: hiring a coder who does not use a wheelchair over an equally qualified coder who does use a wheelchair.

Not Ableist: regarding candidates in wheelchairs as having a lack of capacity to work as mail carriers in a rural area that requires going up and down steep driveways to deliver packages.

Ableist: not considering me, a deaf person who uses hearing aids, for a job editing your Substack since you would be annoyed by having to text me before all phone calls to say “Hey Holly, going to call you in a few minutes so please turn on your hearing aids.”

Not Ableist: not considering me, a deaf person who uses hearing aids, for a job doing sound effects editing for your podcast (or any other job that requires the ability to make fine sound-distinctions based on what people with normal hearing will hear).

Ableist: not considering a type 1 diabetic for a job they are otherwise qualified for because of their diabetes.

Not Ableist: requiring a type 1 diabetic to test their blood sugar and correct it before starting their shift as a bus driver, pilot, or other job where safety is on the line.

Fetterman’s Problem Is Not The Closed Captioning

Anyone who watches the Fetterman/Oz debate, which you can do here, can tell that Fetterman’s problem was not closed captioning. (One of the excuses going around is that the closed captioning was slow or otherwise malfunctioning.)

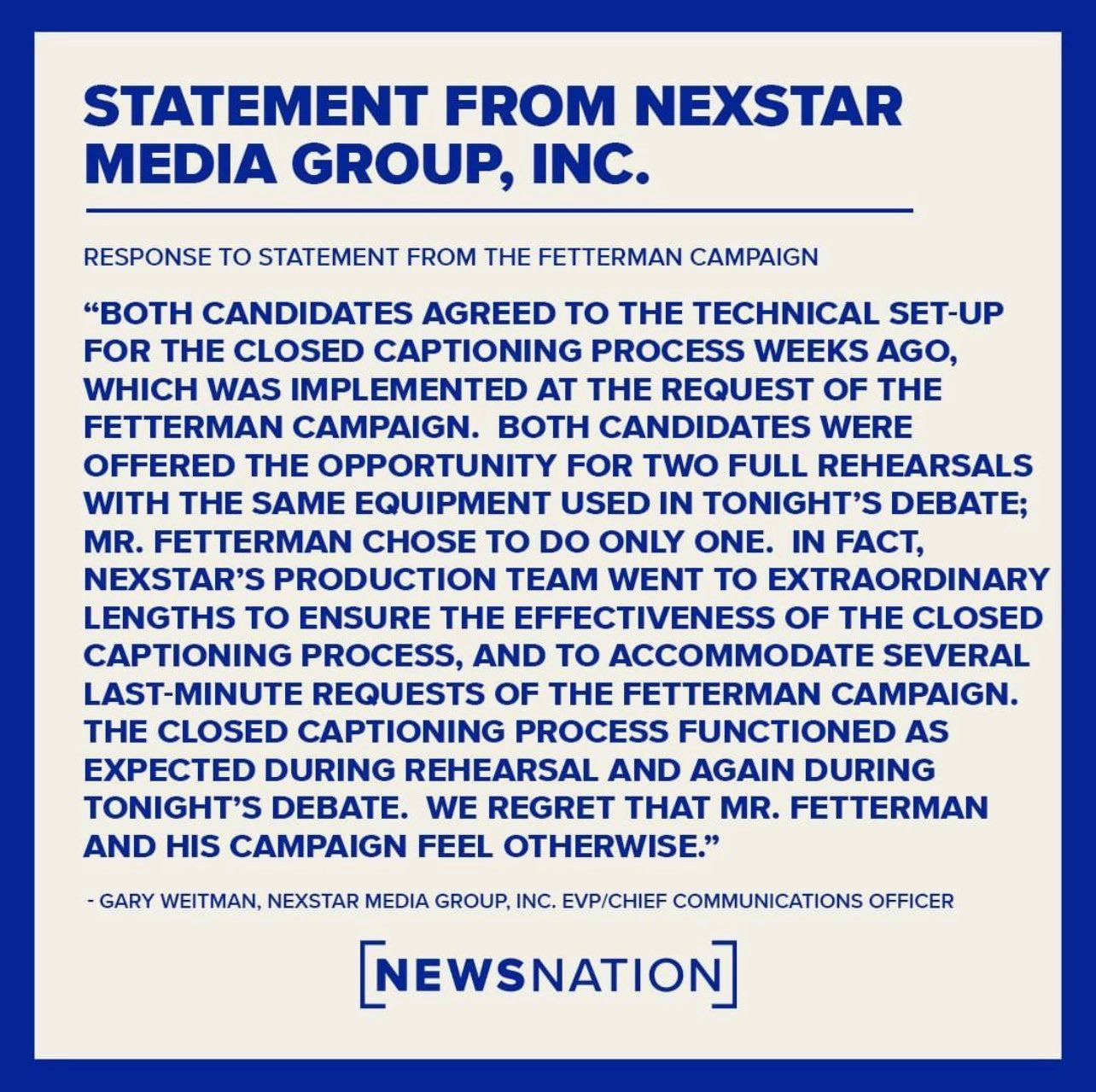

Statement from the company that provided the captioning:

First, this attempt at an excuse is stupid. If the closed captioning was malfunctioning, Fetterman was free to say, “The closed captioning is malfunctioning. Can we take a break and fix it before we continue?” Unless, perhaps, he lacked the capacity to recognize and articulate that situation, which frankly wouldn’t surprise me.

Fetterman’s debate performance gives evidence that he is, as of now, disabled in a way that prevents him from understanding and responding to language in a reliable fashion. He was repeatedly unable to answer clear and direct questions in a coherent way. He had some canned lines that he repeated, but he did not seem to understand when asked to clarify or explain. His cheerleader-style chanting of “Roe! V! Wade!” was odd—not on content; support for the previous state of abortion rights under Roe vs Wade is a defensible position. It was odd for the way it communicated an inappropriate affect and no understanding of how his language was wrong for the context and what he was presumably trying to communicate.

I don’t mean that he dodged or re-directed the topic of questions the way that politicians normally do. The fracking question is probably the best example of this: here is that clip. It’s a little over four minutes, and well worth it. Both candidates have contradictory histories on fracking. Compare the normal politician-dodge that Oz pulls with the starts-off-mostly-ok, then quickly- degrades-into-confusion response from Fetterman. The moderator correctly presses Fetterman on his contradictions, and he can do nothing but repeat the canned lines his staff had him memorize. He cannot think and respond in real time.

What Is Reasonable Accommodation?

The Americans with Disabilities Act requires schools, government, and most businesses and employers to provide reasonable accommodation to disabled people. This is right and just. Further, it enables people like me to earn money and pay taxes, rather than go on the dole and collect disability benefits, so it benefits everyone.

A reasonable accommodation is one that allows the disabled person a fair chance at performing as well as a peer without that disability.

As an undergraduate, I received disability accommodations for my anxiety disorder (PTSD) and for my deafness. I was offered many more accommodations than I accepted (which is another essay; perhaps I’ll write it if there’s interest). Here are the ones I accepted, and why they were reasonable.

Peer Notes. My university had a system whereby students who were good note-takers could get community service credit for uploading their notes to a special portal. Students with an accommodation to receive peer notes could then access those notes. This was a reasonable accommodation because my hearing often meant that I missed things or misunderstood things. As a mathematics major, most of my classes were taught in the most difficult way possible for a student with limited hearing: with the professor’s back to the class, while writing on the board. Peer notes let me focus all my energy on listening, knowing that if I missed something, I would get it from the peer notes. This meant that when I wasn’t sure if the professor had said “15” or “50,” or when I wasn’t sure if I had heard “secant” or “cosecant,” etc., I could relax and continue listening, knowing that the peer notes would be available to supplement my own. This accommodation let me have the same level of access to the lecture as a student with normal hearing.

Preferred Seating. This accommodation allowed me to choose my seat in every class and required the professor to make any adjustments required to enable me to keep that seat. The reason I needed this accommodation is that at the time I was unable to sit with my back to the door of any room. (With hard work in therapy, my PTSD continues to get better, including in this respect.) There were some classrooms with all student seating in positions where the students’ backs were always to the door. When this happened, I would sometimes move a desk so that I could see both the professor and the back door. Other times, I would sit in the back row on the very end and angle my desk slightly so that I had an easy view of the door. This enabled me to participate because I was not overcome with anxiety and adrenaline from being unable to tell who was entering the room and why/how I could escape if needed. It also freed the professor from having to try to “take care of” me in any sense; I decided where I would sit and all he or she had to do was accommodate my decision (generally requiring them to do nothing at all).

Extra Time. I almost never used this accommodation, but when I needed it, I really needed it, so I always kept it on my record. One example of a time when I really needed it? A drunk man (who, with the classic timing of terrible luck, looked a lot like my abusive father) accosted me on the city bus, put his hands on me, and threatened to kill me, on my way to take my Calculus 2 final exam. I arrived in a state of full PTSD triggering, by which I mean that even though my adult brain understood that I was on campus taking a final exam, my nervous system thought that I was seven or eight years old and had just been roughed up and threatened by my father again. I was full of adrenaline, with the taste of metal in my mouth and my heart rate 50% higher than normal. In that state, I was supposed to sit down and do trigonometric substitution integrals that required thirty steps to complete, to remember which convergence test to use for which sequence, and do all the rest of what Calculus 2 requires. The extra time accommodation let me sit there and spend the first half hour just breathing, trying to calm myself, and using techniques I learned in therapy to try to return to my baseline. I then took the test one problem at a time, taking short breaks after each problem. As a result of the accommodation, I had a fair shot at PTSD not affecting my performance.

Use of the Testing Center. My university maintained a testing center for students who received disability accommodations. The staff there were fully cognizant on each student’s accommodations. When I arrived, a testing station (with a chair that would not place my back to the door and provided a clear view of a clock) was ready for me. The staff would also connect with me and we’d plan my breaks, if I intended to use them, and anything else I may need to access my accommodations at that time. This was more for the professors than the students, freeing them from having to directly provide the accommodations themselves, but it was a good situation to take tests in and I often used it.

Some Disabilities Do Affect Capacity to Perform

And it isn’t ableist to say so.

Ableist: regarding a deaf person who needs closed captioning or an American Sign Language interpreter to participate in a pre-election debate as unfit to serve in the position they are running for.

Not Ableist: regarding a stroke victim who has obvious cognitive impairment affecting his ability to understand language and respond using language as lacking capacity required to do the job of Senator. Senator is a job for which understanding and using language, particularly responding to arguments in real time, is a crucial capacity.

Extremely Fucking Ableist: comparing the situation of a deaf person with normal cognitive capacity who requires a linguistic accommodation to that of a stroke victim who should be in a hospital doing intensive rehab to get his brain working properly again.

Seriously, people. Just stop.

Housekeeping: Now through Halloween, paid subscriptions are 10% off: link here. Comments are open for paid subscribers. Email hollymathnerd at gmail if you want to participate but can’t afford a paid subscription. I’m no longer on any social media, so your spreading the link to anything you enjoy reading here is helpful and appreciated. Thank you!

I found this a super helpful explanation of appropriate accommodations. Thank you so much for being so clear, it really helped me understand the issues better. I also really appreciate that you shared your story about requiring extra time to write your calculus exam. It just made so much sense to me and gave me an insight into your experience which is shared by others in my life. It helps me understand them and for that I am truly grateful.

This is a really good essay. Thanks for your insight from the perspective of a deaf person. As someone who also doesn't hear well, I've been annoyed at the comparisons of Fetterman to deaf/hard of hearing people who require closed-captioning. Not the same thing at all!

I have a question for you, regarding deafness/hard of hearing. I never know what to call myself. I feel a little like I'm "being a victim" if I say I'm deaf (because I can hear sounds and never had to learn sign language, though that might have helped), but "hard of hearing" doesn't seem like ... enough. Like you, I require hearing aids (well, just one hearing aid, since one ear is almost completely deaf and doesn't benefit from one). Even with the hearing aid, I avoid talking on the phone because it's exhausting, and I can't understand people with accents. Women's voices are especially hard for me to understand, and if there is background noise at all ... forget it! I depend on closed-captioning when watching YouTube or TV.

Over the years, I've learned to "hear" by watching people's mouths and picking up on context clues. That doesn't always work, so I'm a master of the smile and nod, though I've also gotten less self-conscious about asking people to repeat things or write them down.

Would you call that deaf or hard of hearing? Thanks.