Conjoined Twins and Collectivism

reflections on individuality

This post has a ton of pictures, so your email client may have a freak-out. Click on the title above to read it at the Substack website.

Two Sets of Conjoined Twins

A few years back, I had a bad case of mono.

While sleeping my way through most of a semester, I watched a lot of television to pass the time, including the niche channels at the upper end of the cable offerings. On one of the niche channels, the daytime schedule seemed to play, almost entirely, old reruns of Oprah. I enjoyed these for both the historical perspective and the human drama.

One episode featured no studio audience, just a pair of 6-year-old conjoined twins, Abigail and Brittany Hensel.

I became fascinated by Abby and Brittany, and read absolutely everything available about them. There wasn’t much, but I even went to the library and got a librarian’s help to read microfiche and microfilm archives of things that had been written before the internet, as the twins were born in March of 1990.

They were born in Minnesota. Their parents didn’t know they were having conjoined twins. In fact, they didn’t even know they were having twins at all.

This was the first pregnancy for both of their parents, who were already, understandably, nervous. They went to the hospital expecting to come home with one baby. Instead, they had the twins, and everyone in the delivery room was shocked.

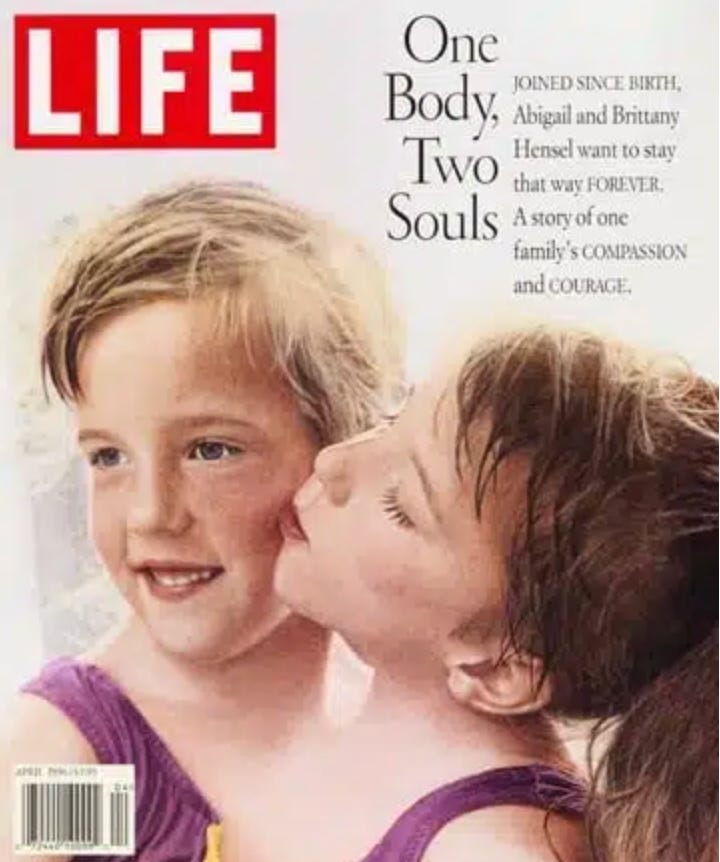

In a 1996 LIFE magazine article, the parents recount: “They had a pretty crude way of telling us,” says Mike. “They said, ‘They’ve got one body and two heads.’” Patty, still woozy, didn’t understand at first: She heard the word Siamese and thought, “I had cats?”

I’ve had pregnant friends report this to me as a nightmare. Imagine actually experiencing it. Imagine giving birth, or working in the delivery room during the birth, of what appears to be a two-headed baby!

As dicephalic (essentially, one body, two heads) twins, the girls share too many vital organs for separation to have been an option.

They are now 34 years old, teach the fifth grade, and are married with a stepdaughter. When they got married, it was Abigail’s name that went on the marriage license. But given their situation, in particular the fact that they have one set of genitals and reproductive organs, I think it’s a fair framing of the situation to say that they are both married, and the single name on the marriage license is in deference to bigamy laws.

My interest in Abby and Brittany led to an interest in other conjoined twins, of which I could have chosen several to mention here. I went through periods of near-autistic obsessions as a kid, wherein I read and studied everything I could find on a topic. One of those was conjoined twins, so I know a fair amount about many of them.

But there is one pair of conjoined twins that provides an almost perfect contrast to Abby and Brittany.

The Twins Who Were Willing To Die to Be Separated

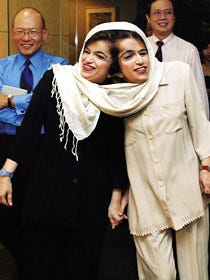

This is a picture of conjoined twins Ladan and Laleh Bijani.

The Bijani sisters were conjoined twins whose situation was essentially the inverse of the Hensel twins. Abby and Brittany have one body with two heads, whereas the Bijani twins had two bodies with one head. Their skulls and, over time, parts of their brains, were fused together.

The Bijani twins faced a much more difficult life than Abigail and Brittany did. As Iranians, their parents were not free to raise the girls as they wished. They were taken away from their parents and adopted by a wealthy man, who raised them in seclusion. They got a better education than their parents could have provided, but were also turned into celebrities of the “freak” sort and used by their adoptive father for social status and notoriety.

They got away from him in their early adulthood and found their biological parents again, with whom they restored a relationship.

Unlike Abby and Brittany, who ride bicycles, play sports, and do other things with ease, the Bijani twins faced enormous difficulties in everyday life. Simply watching television, for example, required a compromise. The one who faced the television directly must also hold a mirror for the other to see the screen. Everything in their lives was extraordinarily challenging, from sleep and bathing to using the toilet.

This documentary, “Dying to Be Apart,” tells their story. They spent years begging neurosurgeons to separate them and finally found a team of surgeons that was willing to try, recognizing that their quality of life was abominable.

On July 8, 2003, they both died on the operating table, achieving their shared dream of separation only when they were returned to Iran in separate coffins.

The situation of conjoined twins poses profound questions about individuality, which is a concept under serious attack today—one that is surely dying, if not dead already.

Before I expand on my thoughts about individuality and the ways that conjoined twins make me reflect on it, here is a bit more about Abigail and Brittany. I find their situation remarkable for several reasons, especially that their parents are, in my opinion, heroically good parents from whom all of us could take lessons.

Photo Album

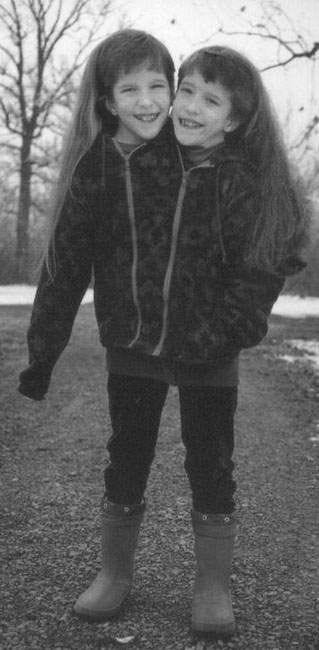

Here are some pictures of the Hensel twins throughout their lives, from early infancy until their marriage a few years ago.

Heroic Hensel Parents

Their mother, Patty, is a registered nurse who works in the Emergency Department of a local hospital. Their father, Mike, is a carpenter and landscaper. The family are traditional Lutherans. They sent their kids to a Lutheran high school. Abby and Brittany graduated from Bethel University, a private Lutheran university.

After having Abby and Brittany, Patty and Mike had two more children—a son and a daughter. Those pregnancies were normal, and those kids seem to have normal sibling relationships with the twins.

The more I have learned about Abby and Brittany’s childhood, the more impressed I have become with their parents. These ordinary people were presented with an extraordinary challenge and, to all appearances, handled it damn near perfectly.

For starters, they refused to subject the girls to any unnecessary medical testing. People who wanted to study them just to learn about conjoinment were told that if the girls wanted to volunteer for such as adults, that was fine, but as children they were going to have the most normal life possible—which meant a firm “no” as long as the decisions were in their parents’ hands.

They controlled the media like masters, and seemingly just by operating on common sense and their own good instincts. They did the Oprah interview when the girls were six, in front of an empty room, so that their first major interview wouldn’t involve memories of adults gawking at them. The full episode doesn’t appear to be online, but here’s a short clip. Mike and Patty also allowed a LIFE magazine writer and photographer to do an article, the one previously quoted from, at around the same time.

Then they did documentaries around their 12th and 16th birthdays.

With this strategy, the girls got just enough media exposure that a lot of people had heard of them and knew something about them, which helped them when they went out into the wider world. But they had normal lives otherwise, with as much privacy and normalcy as possible.

The family lives in New Germany, Minnesota, a tiny little town (population 372) with a close-knit community. Consider that the social media revolution hit the world when the twins were teenagers, and yet pictures of them never went viral (that I recall or am aware of). The many people in their community, including other teenagers, who could have used them for content and guaranteed social media clout, simply never did. That makes me proud to be an American. We so frequently fail tests of loyalty and decency, as a people, that this beautiful example of a community being loyal and protective of its members is ennobling.

Their parents engaged a local seamstress to alter most of their clothing to have two necklines, to emphasize their being two individual girls. They also made a point of giving the girls individual gifts and making them feel special as individuals, despite the permanent presence of a sibling making one-on-one time impossible.

The most important thing they tried to get across to their twins was that their conjoinment was neither a crutch nor an excuse. They made sure to give the girls all the normal opportunities of kids growing up in Minnesota, from doing chores to playing sports to earning money as teenage babysitters.

When the girls gave interviews around their 16th birthdays, they politely refused to answer questions about dating and marriage. They navigated those topics with all the self-confidence of young women who were raised to understand that they were entitled to set boundaries and have their boundaries respected.

When the girls went away to college, in the fall of 2008, they at first intended to pursue separate majors. The logistical requirements of going to twice as many classes proved too intense, so they settled on majoring in education with different emphases. Abby likes math and science, while Brittany is into reading and writing. Now they teach fifth grade, and have for the last ten years. The kids in their classes benefit from a team teaching approach, two minds working as one.

Boringly Normal Adults

As college students, the twins accepted an offer to do a reality show. They hoped to earn enough money to help their family by offsetting their college expenses and set themselves up with some more choices in adult life. Perhaps the best evidence of how well they were parented is this: the show only lasted one season because there wasn’t enough conflict or drama. They were simply two normal, well-adjusted, responsible young women. Their show revealed the mundane life of two serious students with friends and varied interests, going to college and navigating the world, who happened to be conjoined twins. They weren’t screwed up and their lives didn’t involve drama or facing the consequences of dumb mistakes, so a reality TV show about them was just…kind of boring.

Individuality Is A Dying Concept

The situations of conjoined twins provokes some powerful questions about individuality.

I understand the Bijani twins. I think I would be willing to die rather than have a life with absolutely nothing in the way of privacy or autonomy: for literally every decision to require someone else’s approval and, usually, some level of compromise.

Abigail and Brittany’s situation is very different. They are, to all appearances, happy. Their parents report that the one and only time that one of them wished for separation was when they were very sick, as children. One was much sicker than the other, but the healthier twin had better veins and so got stuck receiving the shots and having the IV in her arm. She wished to be separated then, briefly. And that was it.

This acceptance is certainly remarkable, and it may have to do with their faith. They were raised as traditional Lutherans. That is the same faith practiced by their parents. When they got the intense surprise of conjoined twins in the delivery room, their parents simply adjusted to the gift they were given, in their view, by God—the chance to raise two girls with an unusual challenge.

The Hensel twins are able to do many things without consciously communicating with each other, including things that require perfect coordination and that most of us would find impossible to do with a partner: clapping in rhythm, playing the piano, running, riding a bicycle, and driving. They are even able to type, with minimal verbal communication about what they want to say. Their ability to coordinate without verbal communication goes back decades. When they were younger, they played many sports that required them to coordinate their movements without words, including softball and volleyball.

They insist on being regarded as individuals and were raised to think of themselves, fiercely, as such, but they occasionally act in ways that seem to blur the line a bit. This may have changed in adulthood, but at least when they were teenagers, they had a really interesting grammatical habit for communicating via email or instant messaging. When they agreed, they would say “I,” and when they disagreed, they would say “Abby” or “Brittany,” respectively. They never said “we,” and they never gave an explanation of why in anything I saw or read. This habit was explained in a documentary that was filmed in 2006, around their 16th birthday, so it was before the current trend of individuals using “they/them” pronouns, which I find interesting. Upon explaining this habit of theirs, Abby said, “I don’t know why,” seeming to dismiss it without much more thought.

Now That The Twins Are Married

The twins are married, which naturally set the internet ablaze with all kinds of jokes and prurient remarks. Both twins share one body from the waist down, so sexual activity by necessity involves both of them.

What does it mean to be an individual when not even the most intimate of behaviors is yours alone, to choose a partner and have that part of your life be private, special, and sacred?

They share one reproductive system, and as identical twins they have identical DNA. If they have a child, who is the mother? Many children have been born via surrogacy and donor eggs and such, so there is an argument for children existing who have more than one mother in some sense. And of course lesbian couples have raised many children, who may psychologically experience themselves as having two mothers most of the time.

Still, there’s a solid argument that humans always only have one father and one mother, as defined by biology: the source of the sperm and the source of the egg.

But if Abby and Brittany have a child, theirs would likely be the first child for whom an airtight argument of more than one mother could be made: shared ownership of the egg and identical DNA.

What would it mean for a child to have three parents who were fully and biologically their parent, in every sense?

What Makes The Twins Individuals?

In the LIFE magazine article—I own a copy, purchased from an eBay seller—the twins’ different personalities are commented on at length. It was written when they were six, so these differences go back to their earliest years. The following is from the article:

Teamwork is a concept Abby and Britty have grasped more quickly than their peers. Once, after several students got into an argument, the twins led a class discussion on how to get along. “They’ve definitely had to do that their entire lives,” says (their teacher).

It can’t have been easy. Their different temperaments have been apparent since infancy. Abby has a voracious appetite; Britty finds food boring. Abby tends to be the leader (“She wants more things and is more diplomatic in getting them,” says paternal grandmother Dorothy); Britty is more reflective and academically quicker.

The article also makes an astute observation about the “nature vs nurture” question:

To J. David Smith, a professor at the University of South Carolina who has written on conjoined-twin psychology, the individualism of siblings born of a semidivided egg sheds light on the nature-nurture debate—the question of whether we are shaped mainly by heredity or environment. If conjoined twins have identical genes (nature) and grow up only inches apart (nurture), what can explain their dissimilarities? Some scientists theorize that the position of each fetus in the womb affects development. Some suspect one twin is dominated by the right brain hemisphere, the other by the left. Smith’s answer is less mechanistic: “It isn’t just genes or the environment. People are actively involved in creating their personalities. They make different choices, choose different directions.” The development of conjoined twins, he says, “Is a compelling study in human freedom.”

What Is Individuality?

In an episode of Star Trek: Deep Space 9, a world that was being considered for membership in the Federation reinstates a previously discarded caste system. Captain Sisko tells them bluntly that caste-based discrimination will prevent them from being accepted into the Federation.

In the idealistic, enlightened future that Star Trek strives to portray, individuals must be free to be judged only on their own merits or lack thereof: on the content of their character, not the caste of their birth.

This is surely one crucial aspect of individuality: being responsible only for oneself (and for one’s children when they are minors).

The most important right endemic to the respect of individuality is, in my view: the right to make important choices for oneself.

Some of these include:

what career to pursue;

whom (and if) to marry;

with whom (and if) to engage in sexual activity;

what religion (if any) to practice, and with what degree of devotion;

what interests and talents to devote oneself to developing;

what personal boundaries to uphold;

what meaning to attribute to one’s experiences and emotions;

what self-perception to hold, and for what reasons;

what sort of creative expression, if any, is important.

The most important aspect of individuality, the one that makes all of the choices above meaningful, is freedom of thought.

Freedom of Thought

Freedom of thought is the ability to think independently and form one's own opinions without undue influence from others.

Freedom of thought influences the ability to choose a career and a partner or partners. It especially matters with regard to religion, self-perception, and personal boundaries. I prize it the most highly because it’s the aspect of individuality that I’ve had to fight the hardest to achieve (to whatever extent I have achieved it…some days are better than others).

Do conjoined twins like Abby and Brittany enjoy these important aspects of individuality? Well, yes and no. They don’t get to decide any of these things alone, and must compromise with a sister to actualize anything the sister isn’t participating in. They compromised on becoming teachers, but it was a decision they both had input into. They married the man of their choice. By all known information, they don’t suffer from any tragic complications that would make reasonable compromise absolutely impossible, such as one being gay and the other straight.

A conjoined twin who wants to take a painting class may have to bargain with a sister who doesn’t, offering something in return. Self-perception is one’s alone, though other people—particularly parents—can influence it, often in ways that are extremely difficult, though possible, to alter. But having another person’s ongoing presence literally all the time surely influences it as much as particularly good or bad parenting does.

Freedom of thought is sometimes difficult to respect in others, but since when are the important things easy? A few examples of times when I have struggled to respect other people’s freedom of thought follow.

A friend of mine was sixteen years old when he lost his virginity to a much older partner, a man of about twenty-five. (No, this story is not about

— I have other gay male friends.) He insists that he was in no way victimized and remembers his sexual initiation fondly. If his partner had been found out, he swears, he would not have cooperated in any way with a prosecution. He was a willing and consenting participant.I find his perspective troubling. I know that some things really are different for men, but I find it hard to believe that the power differential between a 16-yr-old and the man who had to drive him home because he couldn’t yet drive himself wasn’t unequal enough to nullify his consent. But I also know how absolutely maddening I find it when other people interpret my own experiences for me, so I have to respect his freedom of thought to decide, on his own, what that experience was, and what it meant. He may see it differently when he gets older, or he may not, but that is entirely up to him.

Likewise, I know a beautiful Muslim woman who regards hijab as liberating. She believes that covering her hair causes men to regard her as some kind of sex-neutral equal. I think this is ridiculous. I suspect that covering her hair makes men think of her in more sexual terms, not less. A Muslim woman with no wedding ring who takes her faith seriously enough to wear hijab is likely assumed, by straight men, to be a virgin. My intuition is that she’s regarded as exotic, naive, and submissive, and a great deal of the male attention she believes to be respectful is at least partially motivated by prurience. But again, her faith and her expression of it both have enormous meaning for her, and freedom of thought entitles her to interpret her experience in the world as she wishes.

Neither of these examples are meant to suggest that close friends can’t discuss, and disagree about, these things. But the key word there is “close.” Good friends who understand each other deeply can talk about deep issues of individuality and identity and disagree on their meanings without the consequence of disrespect and erosion of each individual’s freedom of thought. I have a friend like that in Josh, and though those conversations are sometimes painful and difficult for both of us, they’re always worth the vulnerability and effort. I have learned a lot about myself from him, both directly and indirectly, by being willing to be vulnerable and go deep.

But these kinds of conversations, between individuals who’ve earned the right to go deep and done the prep work required for real vulnerability, is not, by and large, what I see in the world around me.

Individuality Is Dying

Andrew Breitbart said, “Politics is downstream of culture.” I think he got that right, though I understand arguments that the river of causality flows in the other direction. But as far as I can tell, individuality doesn’t seem to exist as a respected ideal anymore in politics or culture.

Americans seem to be replacing rugged individualism as one of our highest virtues with tribal loyalty. Individual character traits, ethics, and abilities are no longer markers of virtue; rather, adherence to the desired ideology is the highest good. This is why, the vast majority of the time, knowing someone’s position on one issue—gun control, man-made climate change, etc.—allows predicting, with very high accuracy, their position on nearly all other issues.

We are turning into collectivists, and it’s quickly destroying everything that once made America exceptional.

Everyone is to blame for this, including me and you. The left instituted identity politics, a way of looking at the world where one’s immutable characteristics are supposed to inform and shape one’s political views and behavior. The right has its own version, often while pretending not to.

I recently read two essays on the same day. One, by a lefty, blamed white women for the country’s descent into fascism because white women have voted Republican in all but two elections since data started being reliably kept on such demographics, in the early 1950s. It warned of the wrath of all people of color if Trump wins in November. The other, by a conservative, blamed white women for the country’s descent into wokeness. It warned of the wrath of all white men if Trump loses in November.

I chose that example not because I’m a white woman — I’m retired from commenting on politics and I probably won’t vote because I live in a cobalt blue state and regardless, I now actively refuse to care. Rather, I chose it because it’s a beautiful example of the fallacy of tribal reasoning. No matter what happens in November, the tribal thinkers on both left and right already have their explanation ready. The articles blaming white women could be (and some probably are) written in advance. They already know whose fault it is and who bears the moral responsibility, and it hasn’t even happened yet!

Critical Thinking vs Ideology

One of the core rules of critical thinking is this: if you’re equally good at explaining any outcome, you have zero knowledge. The one and only thing that being equally good at explaining any outcome means is that you’ve adopted an ideology.

Ideology is the enemy of individuality. It shuts down possibility, negates the power of growth, evolution, and change; imposes rigid conformity, and overrides autonomy. It replaces freedom of thought with scripts. It crushes the creative spark that is every human’s birthright, and it must always be resisted by anyone who wants to hold onto her individuality.

An ideology is not a worldview, though some people use the terms as synonyms. Worldviews can take in new information, can be flexible, and are not equally good at explaining any outcome.

What’s the difference?

It can be hard to articulate, but one clue that a worldview has become an ideology is that it gets called a religion by reasonably smart onlookers. I think there’s a good reason for that. The primary difference is that ideology is prescriptive, and worldview is functional. A worldview can be informed, dominated, or wholly defined by an ideology, but in the end it is the functional interface between the individual and the world, while an ideology is a system of abstractions and prescriptions (usually moralistic ones) based around a core doctrine.

Some types of religious people (supply your own “not alls”) give a solid example for the rule of critical thinking: “if you’re equally good at explaining any outcome, you have zero knowledge.” That principle is part of how I, as a teenager, came to the conclusion that the adults around me were full of shit. When good things happened, a loving God was blessing them. When bad things happened, a loving God was testing them.

That a loving God existed and found them, personally, to be extremely important and valuable and worthy of His direct attention, intervention, and unending love — this notion was as unfalsifiable as it was axiomatic. The thing they most wanted to believe to be true, rather than being supported by evidence, was simply declared true and then everything twisted into supporting evidence.

Creeping Collectivism As Harbinger

I’ve read almost every book written in the last thirty years by North Korean defectors, and they scare the hell out of me. Their Communist system holds individuals responsible for the crimes of their ancestors. This caste system, called songbun, splits citizens into three groups: core, wavering, or hostile — and this is based on the behavior of the ancestors, who died before the citizens affected by this sorting were born. When teenagers are finishing school and assigned their adult fates, it doesn’t matter how intelligent, talented, or hard-working they are. If they were born into the hostile class, they’ll be lucky to get adequate food, much less an opportunity to make something of themselves. This is stupid beyond words, as it wastes the talents of many citizens who could do something great for the benefit of the entire nation.

But these things seem normal to North Koreans, because the concepts of individual achievement and freedom of thought do not exist for them.

North Koreans have no understood and respected right to privacy or bodily autonomy, no ability to say something disloyal or intemperate without drastic consequences (imposed by other citizens, typically—much more often than by the state), and they are held responsible for the crimes of a group they did not choose to join.

Wow, does that sound familiar.

Americans seem to me to be heading in this direction, and for the most part voluntarily. This isn’t a political rant on my part, by the way. This dynamic has almost nothing to do with who gets elected, or doesn’t. Americans are simply becoming more and more tribal, and electing someone from the Blue Team vs the Red Team merely shapes the journey we’re already on. Are we heading into collectivism via higher taxes and blaming people with less pigmentation for our problems, or are we heading into collectivism via lower taxes and blaming people with different beliefs about the creator of the universe for our problems?

Either way, we are headed into collectivism.

I object.

I do not volunteer.

I am going to root out tribal thinking from my own worldview, because I see it now for the poison that it is, and I absolutely fucking refuse to continue.

This will be a difficult challenge, but I can do it.

I found a way to stop blaming every man for the pedophile who blighted my childhood. Just as I came to understand that not every man is guilty of those crimes, I am not responsible for the crimes of other women, other white people, other atheists, or anyone else with whom I share an immutable or changeable characteristic—or don’t, for that matter.

This will only ever change if I someday legally adopt someone, and then it will only be true until he or she reaches majority.

I demand my right to be held responsible for myself and and only myself.

Abigail and Brittany Hensel are permanently responsible for someone else.

I am not, and neither are you (the obvious exception of minor children aside).

Individuality is the most precious gift we have, and I refuse to squander mine.

If enough of us reclaim our individual agency, then a collectivist future might be avoidable, if it isn’t already too late.

If we aren’t too far down this road to turn back.

Star Trek Again

The first truly great episode of Star Trek: the Next Generation is season two’s “Measure of A Man.” In it, the android officer, Lieutenant Commander Data, is forced to go to court to have his sentience and his right to individual liberty legally recognized.

His dear friend, Commander Riker, is forced to act as prosecutor and try to prove Data doesn’t deserve rights. The episode is brilliantly written and acted, but brutal to watch, as viewers can’t help fearing for Data’s future—disassembly at the hands of a scientist who wants to force Data to be the prototype for a race of android slaves—and imagining being in Riker’s shoes, forced to argue against the rights and freedoms of someone you love.

At the end of it, Data wins. The presiding judge says in part: “This case has dealt with metaphysics, with questions best left to saints and philosophers. I'm neither competent nor qualified to answer those. But I've got to make a ruling, to try to speak to the future. Is Data a machine? Yes. Is he the property of Starfleet? No. We have all been dancing around the basic issue. Does Data have a soul? I don't know that he has. I don't know that I have. But I have got to give him the freedom to explore that question himself. It is the ruling of this court that Lieutenant Commander Data has the freedom to choose.”

The freedom to choose encompasses everything I described as part of freedom of thought, and this freedom is of course one that is severely limited for conjoined twins.

It doesn’t exist at all for North Koreans, and we Americans seem to be happy to give it up in the name of tribal loyalty and the perceived safety of connection through conformity.

Can we turn it around?

Yes, we can—if, as individuals, we insist on our right to not play for any team — not the Red Team, not the Blue Team, not any other team. Nor are we responsible for the actions or lack thereof of any “community” we do or don’t “represent” by the happenstance of some immutable characteristic.

This is the only way to protect freedom of thought: by refusing to cede it, and by rooting out every collectivist weed from the gardens of our minds.

I’m going to.

Y’all are individuals. Do what you want.

Abby & Britanny were (are) college friends of my younger son. I have met them several times and they are very well adjusted ladies given thier lot in life. It is impossible not to do a double take of course when you see them, but they are gracious and understanding about the gawkers.

Another classic essay! On current evidence I think I can safely say I prefer your new direction in writing to the old one.